David Cicconi

In the 24 years since the Netherlands liberalized its drug laws, Amsterdam has become a pot smoker's theme park. In nearby Haarlem, Holland's hemp culture teeters on the verge of respectability. How far can these cities push the limits of Dutch tolerance?

David Cicconi

In the 24 years since the Netherlands liberalized its drug laws, Amsterdam has become a pot smoker's theme park. In nearby Haarlem, Holland's hemp culture teeters on the verge of respectability. How far can these cities push the limits of Dutch tolerance?

A Misty Morning in Amsterdam.

Patrons at barney's Breakfast Bar on the Haarlemmerstraat order scrambled eggs with a side of corned-beef hash or, if they prefer, a side of Nepali Temple Ball hash. Down the street at Blue Velvet, hipsters sip espresso, smoke THC-rich Thai stick, and practice looks of ennui. At the Grasshopper, on the edge of the Red Light District, souvenir-toting tourists queue up to anesthetize themselves with a pipeful of Holland's infamous skunk weed.

Amsterdam.

The Big Bud. Aboard its trams and trains, on the brick streets and broad squares, even in the main concourse of Schiphol Airport, the sweet smell of marijuana is as pervasive as diesel fumes in Mexico City or the aroma of curry in Bombay.

Visitors these days are less likely to want a tour of the Heineken Brewery than a tour of the city's notorious coffee shops-and not for a caffeine fix. Nearly a quarter of a century has passed since an amendment to the Netherlands' Opium Act of 1919 opened the way for licensed coffee shops to dispense weed and hash. They really do serve coffee alongside the cannabis, though seemingly more as a polite pretense than as a source of profit.

The purpose behind the 1976 amendment was to keep casual users of soft drugs away from the dealers of heroin, cocaine, LSD, and other hard drugs. Pot possession was decriminalized, and its use was eliminated as an offense. About the only thing the legislature didn't do when it liberalized the laws was erect a sign at Schiphol saying duuuude!

Dutch towns were allowed to set up their own regulations for coffee shops. Some banned them outright; others, specifically Amsterdam (with as many as 400 coffee shops today), embraced the policy with gusto. "Cough shops," as they're sometimes called, have proliferated throughout the Netherlands, but those in Amsterdam are sui generis. Clustered in or near Dam Square, the Red Light District, and the Leidseplein, they often attract more tourists than locals. Many of these foreign visitors, trying to cram as much excitement as possible into their week's vacation, tend to overindulge-imbuing places like the Bulldog and Hill Street Blues (next to the Warmoesstraat police station) with the raucous mood of a frat party at Grateful Dead U.

That picture is a hard fit with the traditional Dutch images of tulips, wooden shoes, and windmills. "The coffee shops are just horrible," says Pam Kragen, a newspaper editor in San Diego County. Although she had traveled widely, Kragen wasn't prepared for the openness of Amsterdam's drug scene during her first visit in the mid eighties, when the coffee-shop frenzy was at its height. "The smell of marijuana, the rudeness. The coffee shops and public drug use aren't what you'd think the city would want to present to the world."

Even Amsterdam's city fathers admit, with typical Dutch understatement, that the situation had gotten out of hand. After closing nearly half the city's coffee shops two years ago for selling hard drugs, among other violations, Mayor Schelto Patijn told the London Sunday Times, "We let things go a little too far."

But just 10 miles west, a mere stoner's throw yet worlds away from the circus of Amsterdam, lies Haarlem, which many consider to be a model of the coffee-shop system. In 1994, a rare collaboration among the police, city hall, the district attorney, and coffee-shop owners established the current local policy. Although the city had more than 20 coffee shops at the time, it wanted to limit the number, by attrition, to no more than one for every 10,000 residents, or 15 shops (today there are 16). The coffee-shop owners also had to agree to abide by national regulations that bar patrons under the age of 18, prohibit the sale of alcohol, and limit the amount of pot that can be sold to each customer. In exchange, officials agreed to let the shops operate unmolested.

Gerard Silvis, a 25-year veteran of the Haarlem Police Department, is the chief liaison with the coffee-shop owners. "The situation is much better than it ever was," he says. "It used to be full of criminals. It seemed as if there were no rules. Most of the police like the present policy. With bars we have a lot of problems, but almost none with coffee shops. In the past year we had only a single complaint from the sixteen shops, and that was because a seventeen-year-old had entered one of them."

Fred van Boxtel, manager of the Theehuis, says the police make official visits every couple of months, not only to scan the crowd for minors, but also to ensure that the shop carries no more than the 500-gram-maximum inventory of pot and hash. "Nowadays," he says, "we have a great relationship with the police."

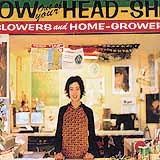

To a large extent, a relative lack of tourists contributes to the tenor of Haarlem's coffee shops. Instead of the loud rock music, party-hearty atmosphere, and low-grade cannabis found in many Amsterdam shops, the scene in Haarlem is much more sedate. Some shops reek of sincere amateurism, akin to a cocktail lounge started up by a couple of Nolita 24-year-olds. Others, like Frans Hals, near the train station, have a cosmopolitan flair, with marble cafÈ tables, tall windows looking onto the sidewalk, and an attractive countergirl pouring lattes.

The co-owner of Frans Hals is 46-year-old Nol van Schaik, who also owns two other coffee shops (Willie Wortel Workshop and Dutch Joint) and the Global Hemp Museum in Haarlem. In the pantheon of marijuana martyrs, van Schaik is Haarlem's Pope of Dope and, as he would say, a fugitive from injustice. A former carpenter, bodybuilder, and drug smuggler, van Schaik has been on the wanted list in France since his 1989 arrest at the Spanish-French border, where he was caught attempting to bring 200 kilos of hash from Morocco to Holland. Rather dramatically, he escaped and returned to Haarlem, where he was celebrated at a "Free Nol" rally (the Netherlands later declined to extradite him).

One might think that van Schaik, who smokes 10 joints a day, would be chronically lethargic. But he comes off as vibrant, even visionary. His three shops and the Hemp Museum, devoted to the history of Holland's cannabis culture, are full of affable young customers. You can buy pot with plastic at Willie Wortel; just use the handy ATM machine. Need some rolling papers, a pipe?Drop a few guilders into the vending machine. Van Schaik is planning an international contest on his Web site www.wwwshop.nl. "The winner would be invited to Haarlem to take part in the scene," van Schaik says. "He can be a dealer one day, learn how to grow pot, or just hang out." He dreams of potheads cruising down Haarlem's canals in a waterborne coffee-shop crawl-"You'll be able to rent a water bike and paddle from shop to shop," he says, beaming. He even sponsors soccer teams full of stoned footballers.

Van Schaik's business plan is unexpectedly shrewd. In each of his shops, pretty young women, bright-eyed and smiling, wait behind the coffee bar; a dealer's booth stands near the entrance; tables fill the front room, with pinball or pool in the back. And because the dope stash for all of van Schaik's establishments comes from the same sources (the pot is mostly grown illegally in the Netherlands; the hash is mainly smuggled into the country), the arrangement recalls the uniformity, efficiency, and demographic sophistication of, say, McDonald's. "Right now I employ thirty-five people," he says, somewhat incredulously. "I'm becoming an economic force in Haarlem! I've got shops on all four sides of the main square. No matter which way you go, you walk past one of them."

At the Willie Wortel dealer stand, Hans Govers, 39, dispenses a wide assortment of pot to an equally wide assortment of customers. You can buy a gram of skunk weed-enough to make two or three joints-for 14 guilders (about $6) or red hair for 12.50. Short on cash?You can pick up a single joint for as little as 5 guilders ($2). "Some people want very fresh weed," says Govers, "some strong, some sweet. If they describe what they like, I can usually advise them what to buy." Govers, who has been dealing since he was 15 and had his own coffee shop when he was 21, looks the part of the stoner dealer-long hair gathered in a loose ponytail, casual shirt with sleeves rolled up, a benign, sleepy expression on his face. "I've been dealing illegally most of my life," he says, "but I've never felt like a criminal. I really like my job. Everything here is very laid-back and friendly."

But how do the dealers get their product?Simple question-not-so-simple answer. Wholesaling, necessary to supply the cough shops, is illegal, but the powers that be conveniently turn a blind eye. "The government knows this is a gray area, a dark hole," says van Schaik, "but they'd rather just leave it as is."

Gerard Silvis of the Haarlem police agrees. "If all I did was wait at the åback door,' I could arrest a lot of people," he says. "But in reality I could do that only once, because then the owners would take deliveries at a different address. Tolerance at the back door is what keeps the system working."

Everyone admits that the back-door policy is a conundrum. "We have to formulate the rules on a daily basis," says Wernard Bruining, who co-founded Amsterdam's first coffee shop, Mellow Yellow, in 1973, before decriminalization, and still actively promotes Holland's hemp culture. "There's no history on this. It's all new territory."

New territory, indeed: even policemen stop in for a 10-guilder packet of locally grown nederwiet or a quick toke and a frappuccino. "I don't visit the coffee shops privately, just professionally," says Silvis, "but there are policemen who go on their own time. We don't say they can't, but we expect them to be discreet, not wear their uniforms."

Politicians relaxing pot laws. Cops toking up. What's next?Marijuana millionaires franchising their business schemes?More likely is the chance that others may heed the Haarlem model-and not just in the Netherlands. Already several European nations are easing their drug laws. Switzerland is considering the licensing of cannabis retailers. The use and possession of marijuana in small amounts is no longer a crime in Spain. In Christiania (a hippie Utopian community north of Copenhagen), the policy of tolerance toward pot is similar to Holland's. Even on this side of the Atlantic, de facto decriminalization in Vancouver has led to a growing coffee-shop community.

"The system in Haarlem is ideal," says Bruining, "an example to the rest of Holland and beyond. Amsterdam has problems because it's so large. But other towns have an opportunity to exercise a real democracy, where coffee-shop owners work with the local government to make everyone happy."