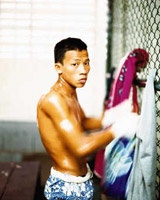

David Cicconi

The vital—and sometimes ferocious—spirit of old Siam lives on in the popular Thai sport of kickboxing.

David Cicconi

The vital—and sometimes ferocious—spirit of old Siam lives on in the popular Thai sport of kickboxing.

If you think you know Thailand because you've stayed at the Oriental or shopped for handwoven silk at Jim Thompson's, here's a swift kick in the head. It's called muay thai, and in a country that has been packaged as an elegant colonial fantasy, this martial art is one of the last remaining tastes of the real, raw Siam.

I've been a fan for 10 years, since I was first dragged to a night of fights by an expat who'd gotten to know the underbelly of Bangkok when it was a wild R&R stop during the Vietnam War. We'd spent a long, sweltering afternoon touring the ornate Grand Palace; I was ready for a quiet dinner. My friend was having none of it. He hailed the noisiest tuk-tuk on the street, and by the time it dumped us in front of old Rajadamnern Stadium 10 minutes later, the serenity of the Emerald Buddha's smile was a world away.

The shadowy entrance was jammed with the kind of crowd that seems just on the verge of a riot. Fortunately, they weren't being kept hungry. Every few feet a vendor was stirring a steaming wok of noodles or mashing spicy papaya salad with a mortar and pestle. My friend ordered a Singha beer and some cheap Mekong whiskey from an old man, who poured each into a plastic bag. "There are no bottles allowed inside," my guide explained, "for reasons that will become obvious."

We walked through the front gate and into a scene right out of Mad Max in the Thunderdome. Spotlights poured onto the center of the ring, where a furious muay thai kickboxing fight was already in progress. The boxers spun, kicked, and, in clinches, kneed each other in the ribs. With every blow, the crowd roared in lusty appreciation. Halfway up the grandstand was a chain-link fence separating the more expensive seats from the bleachers. When the action grew particularly fierce, the rowdies in back rushed down to the fence, shaking it until it seemed as if it would collapse. At the end of the night, I didn't know whether muay thai was the greatest spectacle I'd ever seen or if I should just be happy to have gotten out alive.

It took many more nights at rickety Rajadamnernand the newer Lumpini Stadium before I began to understand what I'd witnessed that evening. While muay thai may be the best pure entertainment in Thailand, it's not so much a sport as a complex cultural tradition, with layers of ritual and hundreds of years of history behind it. It is, in fact, a living relic of the bloody centuries when empires rose and fell in Siam, Angkor, and Burma, when warlords fought endless battles to protect their kingdoms.

Legend has it that all martial arts originated at the Shaolin Temple in China, where an Indian prince named Bodhidharma—who, like Buddha, had renounced his throne to devote himself to religious studies—decided to train his monks in self-defense. These teachings spread to Korea, where they evolved into tae kwon do, and to Japan, where they emerged as karate. In Siam, they became muay thai, the fighting form warriors used when their spears had all been thrown.

Between wars, these fighters practiced their kicks against the trunks of smooth banana trees. Eventually, the training sessions evolved into matches, barefisted contests against fellow soldiers that were almost as bloody as the wars themselves. The combatants later began wrapping their fists with kaad chuek, hemp rope that protected their hands and inflicted greater damage. If the stakes were especially high, the kaad chuek was soaked in sticky tree resin and embedded with broken glass.

Over the years, the rituals surrounding muay became as significant as the kicks and punches. Before entering the ring, each fighter dons an armband called a praijed and a mongkol, a colorful headband that has been blessed by a monk. A fighter might tuck tiny Buddha amulets into his praijed and mongkol, along with other venerated objects such as a strand of his father's hair or a thread from the sarong his mother was wearing when he was born.

That's all a matter of personal taste. Each boxer is required, however, to perform what comes next, a graceful, bouncing dance of homage called the wai khru ram muay; it's eyed closely by the cognoscenti, who gauge the fighters by the integrity of their rituals and bet accordingly. The series of prostrations, which honor the king, Thailand, and Buddhism, is known as "the calm before the storm."

But the calm is not silent. It is accompanied by music that is, by turns, melancholy and frenetic, played on an Indian oboe, two drums, and cymbals. The music continues throughout the match; the fighters use its rhythm to time their attacks.

The last ritual before the battle is the removal of the mongkol by the fighter's teacher. As the instructor does this he whispers an incantation and blows on his student's head three times. If the words are powerful enough, they will protect him. The incantation "Gam ban mak nuen," for instance, means "May my clenched fist weigh a thousand kilograms," granting the fighter the power to knock out his opponent with a single blow. Some boxers, taking no chances, have incantations tattooed on the backs of their hands.

One of the most famous muay thai gyms in Thailand is the Lanna/Kiat Busaba Boxing Camp in the northern city of Chiang Mai. Surprisingly, it's run by Andy Thomson, a muscular Scotsman with a crew cut and an angular face. On the afternoon of my visit to his camp, an outdoor pavilion with rows of heavy bags and two rings, there are 20 boxers sweating and grunting through their workouts. The slap of kicks against leather pads echoes through the air like gunfire.

When I ask Thomson how he ended up running a muay thai camp in northern Thailand, he laughs. "I really don't know—I was working as an engineer in oil fields in India for years," he says. He later moved to Thailand, where he started the camp in his spare time. "I felt at home right away," he says. "Maybe I was Thai in a past life. A psychic once looked at me and said the first thing she saw was an old Oriental man dressed in black."

Of course, Thomson didn't just jump into the ring on a whim. "I'd done eight years of tukido"—an obscure martial art—"but I'd never really been hit. Within five minutes of trying muay thai, I was hooked. It's the simplest, hardest, fastest fighting art in the world."

Over the past 12 years, Thomson has trained a fistful of northern Thai champions. He introduces me to a couple of boxers who will be fighting that night. One is Manat Yingwittayakun, a 13-year-old whose two brothers are training alongside him; the elder one is a former champion in two weight classes. "I'm from around here," Manat says, indicating the hills surrounding Chiang Mai, where his parents are farmers. Manat is a wiry kid with a cowlick that hangs over his forehead. His dark eyes jump around anxiously, perhaps because he lost his first fight to the same opponent he's scheduled to step in against later on.

Working up a sweat in one of the training rings is the fighter who has been featured on the yellow fliers taped up all around town, Mel Bellissimo, a beefy 27-year-old from Toronto. Bellissimo was teaching English at a Chiang Mai grade school—in fact, Manat is one of his students—when he decided to start training.

He takes a breather and confesses that he's embarrassed to be the evening's star attraction: "I'm a farang [a foreigner], and Thais love to see a farang get his ass kicked." I ask how he's feeling. "Well, I'm pretty nervous," he replies candidly. "I'm sure I'll outweigh the guy I'm fighting—I don't think they make Thais as big as me—but he's probably had a hundred fights and I've had one."

My conversation with Thomson turns to the most talked-about kickboxer of recent times, Parinya Charoenphol, who trained here at the Lanna/Kiat Busaba Boxing Camp. Parinya, a.k.a. Nong Toom, was a strong fighter with fast feet, but that's not the reason he became the most famous muay thai boxer in the world. Parinya was a katoey, a transvestite, who wore eyeliner and makeup in the ring. Even in a sport that has none of the macho posturing of Western boxing, this made him a sensation.

"Nong Toom first came to us when he was thirteen," Thomson says. "He lived in the hills within walking distance of here. In three and a half years, he won about thirty fights. A Bangkok promoter heard we had a katoey fighter and couldn't believe it. He booked Nong Toom in Bangkok, and he had a great fight. Then he just blew up—everybody wanted to book him."

Inevitably, perhaps, success eventually led to a falling out between Thomson and Parinya. "As he got more famous," Thomson says, "he didn't want to train. And he wanted to have the [sex change] operation." He finally did, and soon afterward, he, now she, retired from the ring to cash in on her celebrity, singing at a beach resort club in Pattaya, appearing in ads, and starring in a Thai soap opera, as herself. When a Thai film company announced that it was casting a biopic of Parinya's life, more than 300 hopefuls tried out for the part, from boxers to transvestites to roti vendors. The boy who landed it, Assani Suwan, also trained at the Lanna/Kiat Busaba Boxing Camp.

That evening the air is hot and dense in Kawilla Stadium, which looks more like a big cowshed than a sports arena. It has a concrete floor, a corrugated tin roof, and a locker room that is just an open pen blocked off by sawhorses. Inside, Manat looks nervous—even his cowlick is quivering. In fact, he has already thrown up. When he starts making his way to the ring, his 23-year-old brother, the champion, follows in blue jeans and a white T-shirt, massaging the boy's shoulders, whispering in his ear.

The champ's advice doesn't seem to help. In an incredibly inauspicious moment, Manat trips over the top rope of the ring on his way in. Worse, when the fight begins, he slips trying to deliver his first kick and lands on the canvas. His opponent moves in confidently. But Manat recovers, skillfully blocking kicks and punches, and by the second round he's giving as good as he's getting. He pours it all on in the last round, fighting with every ounce of his heart. When it's over, the judges declare him the winner. He goes to his opponent's corner and bows to him, and then bows to his teachers. Only then does his big brother lift him in a bear hug.

As the headliner, Bellissimo has to wait until the last fight. By this time he's a jangle of nerves. He manages the pre-fight rituals, but once the music starts it becomes clear why this is still a Thai sport. He trudges forward repeatedly into a blizzard of kicks and punches, yet never surrenders. He is determined to be carried out on his shield.

When the referee mercifully stops the bout in the third round, Bellissimo bows to his opponent and to his teacher. He is bleeding from a cut above one eye, but he is smiling. "Now," he says, "I am a muay thai fighter."

The two best places for viewing muay thai in Bangkok: Rajadamnern and the more modern Lumpini. Andy Thomson's kickboxing school is in Chiang Mai, also home to Kawilla Stadium.

STADIUMS

Lumpini Stadium RAMA IV RD., PATUMWAN, BANGKOK; 66-2/251-4303; TICKETS $12-$36

Rajadamnern Stadium RAJADAMNERN NOK RD., POMPRAB SATROO PAI, BANGKOK; 66-2/281-4205; TICKETS $12-$36

Kawilla Stadium KAWILLA MILITARY BARRACKS, CHIANG MAI; TICKETS $11

SCHOOL

Lanna/Kiat Busaba Boxing Camp 64/1 SOI CHANG KIAN, HUAY KAEW RD., CHIANG MAI; 66-53/892-102