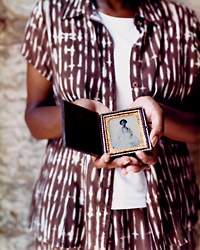

Zubin Shroff History remembered in an antebellum portrait at Charleston's Old Slave Mart Museum

In historic Charleston, where the past lives on in the present and change has long been an unwelcome stranger, 15 years of growth are culminating in an infusion of youth, wealth,

and the culture of the new.

Zubin Shroff History remembered in an antebellum portrait at Charleston's Old Slave Mart Museum

In historic Charleston, where the past lives on in the present and change has long been an unwelcome stranger, 15 years of growth are culminating in an infusion of youth, wealth,

and the culture of the new.

Richard Hampton Jenrette, a well-bred boy from Raleigh, North Carolina, who went north and made good with the Wall Street investment firm of Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, is enjoying the spoils of life one languid Sunday morning at Roper House, his beyond meticulous 1838 Greek Revival home on Charleston's East Battery. In a proper tweed jacket, he sips coffee at his living-room window while taking in the faux paddle-wheel steamers plying Charleston Harbor; the horse-drawn carriages with faux-Confederate guides, followed by equine-sanitation pickup trucks; and the endless parade of tourists gaping at his house as if it were the Magic Kingdom on the verge of blaring out "It's a small world after all."

"Well, I suppose we have become a bit like Disneyland," Jenrette says, "but isn't it pretty? And our tourists do tend to be more cultured people, interested in the arts and architecture—it's not as if they're here for NASCAR."

The fans of choice real estate can be just as devoted, though, especially in March and April, when the Historic Charleston Foundation mounts its annual fund-raiser, the Festival of Houses & Gardens. This year, 150 owners of historic properties in different neighborhoods around the city will open up their homes for an afternoon, and the public will pay in the vicinity of $45 a head for the right to leisurely mill around the epic spreads. The three-story Roper House (houses in Charleston are named after their original builders) is always a hot ticket. Jenrette, who owns five more historic residences in other places, takes particular pride in a suite of restored Duncan Phyfe furniture, Roper House's postCivil War crystal chandeliers, and a Rembrandt Peale portrait of George Washington. His guests have included Prince Charles, Bishop Tutu, and "assorted Rockefellers and Rothschilds."

When Jenrette bought Roper House for $100,000 from Drayton Hastie in 1968, it came with a life tenancy for Hastie's mother. Sarah Calhoun Hastie occupied the piano nobile, or principal floor, with its 18-foot ceilings, for more than a decade after the sale. "She lived to be ninety, a kind of wonderful watchdog for the house," Jenrette says. "Her maid brought her a bourbon every night at cocktail hour, and she always dressed in a velvet evening gown for dinner, even if eating alone."

The "too poor to paint, too proud to whitewash" aesthetic is still part of the velvet madness in this insanely beautiful city. Many of Charleston's old guard trace their heritage to the early English colonists, who laid out a series of broad, elegant boulevards according to a British Grand Modell plan, creating a city that came to be called Little London. Here, where the first American Museum Society was organized, in 1773, most of the grand houses, built by slaves in a dizzying array of architectural styles—Colonial, Federal, Georgian, Italianate, Victorian—still stand, protected by law since the early 1930's. Over the ensuing decades, as one old-family sort notes, the houses were "preserved by poverty." The occupation by "tacky tourists" didn't begin until the late 1970's; after Hurricane Hugo hit, in 1989, insurance money fueled the first great real estate boom, and everyone got in on it.

Now Charleston, one of the most concentrated enclaves of the wealthy in the United States, is vying for the title of the South's most venerable theme park. In the neighborhood known as downtown, south of Broad and the commercial district, blocks of once decrepit but still graceful properties are now as clinically spruced up as Colonial Williamsburg, and lousy with overwrought landscaping and Rolls-Royces. For each gain there is a loss: every dinner I had with the regal social doyennes of Charleston, women whose grandparents had streets named after them, would end on a bitter note with the obligatory drive past the imposing mansion the family used to own—inevitably done to death by some vulgar Yankee.

For a time, the natives held on through creative financing—such life tenancies as Sarah Hastie's were common. Today, in a city where sharing the past is often synonymous with making a living, everyone caters to the tourist trade in one way or another. A short walk away from Roper House, Drayton Hastie's 1843 Battery Carriage House, where Sarah Calhoun Hastie was raised, is now an inn of the same name. The mood there is slightly more democratic these days: most of the guest rooms are out back in the dependency, former slave quarters that still offer a prime view of the swells in the ballroom. Jenrette's next-door neighbor Charles Duell still lives upstairs in the Greek Revival Edmondston-Alston House, which is open for public tours throughout the year. On the other side of Roper House is the 1848 Palmer Home, an 18,000-square-foot mansion known as the Pink Palace, now a quirky bed and breakfast run by Francess Palmer, who likes to point out the valances given to her mother by Dina Merrill and the imposing Hepplewhite table in the dining room. "Every day at two-thirty we had a formal family dinner in hose and heels," Palmer says. "My grandmother hid a bell under the rug so the servants would appear magically. Now, that's my job."

Meanwhile, on the other side of the historical continuum, Charleston is stretching into the future. The city even has the mandatory late-breaking hip district: On King Street, north of Calhoun, a string of funky old establishments—What-Cha-Like-Gospel; Reuben's, "The store that puts the change on you," offering the Steve Harvey line of flash wear; and the chockablock Honest John's Record Shop for lawn-care service, pigs' feet, and even records—serves as a backdrop for such newcomers as the supremely edgy B'zar, a "Shop for your lifestyle" with such neo-hipster items as Kidrobot toys. B'zar is owned by Gustavo and Andrea Serrano, a young husband-and-wife team who moved down south from Brooklyn last year. Gustavo, for one, is ready to ride the vibe: "The quality of life in Charleston is amazing, and this section of town has so many great new things: the restaurants 39 Rue de Jean, Coast, and Raval, a martini bar called Torch, and really interesting shops like Urban Electric, Dwelling, and Leigh Magar, who makes these really fantastic hats. I love living in a city that has yet to happen."

On the culinary front, such stalwarts as Charleston Grill, Circa 1886, and Peninsula Grill have yielded to the new era of reimagined Southern fare—the tweaked shrimp and grits at establishments such as Slightly North of Broad and the advanced regional cuisine at places like Hominy Grill. Robert Stehling, Hominy's chef and owner, operates out of a converted barbershop with pine floors, dishing up such adventures as ginger-accented coleslaw and Southern fried chicken with country-ham gravy. To Stehling, the horizon is unlimited: "The restaurant scene here hasn't found a good Southern focus yet. We need to look at what's unique about the low country, the fabulous food that came from the black cooks in the homes of the wealthy rice planters."

In fact, this is not the first time Charleston has propelled itself into the modern era. In the 1920's, the Charleston Renaissance movement embraced artists, jazz musicians, social innovations like the cocktail party and the Charleston dance craze, and writers on the order of DuBose Heyward—whose novel Porgy, about life on Catfish Row, did pretty well as the Gershwin opera Porgy and Bess. Today's Charleston renaissance is fueled by the Spoleto Festival every spring, though on any given day the cultivated set of the city matches the sophisticates of London or Paris. Some of Charleston's more prominent contemporary writers, for instance, include Sue Monk Kidd (The Secret Life of Bees); Josephine Humphreys (Rich in Love); and Edward Ball, who wrote the National Book Awardwinning Slaves in the Family, detailing his shame over the Ball family's control of some 4,000 slaves.

In the end, what you take away from any city are the people, and Charleston's neo-Dixie intelligentsia—people like Charlie Smith of the gay social justice group Alliance for Full Acceptance—are forever teetering between the tug of the past and the rush of the new. Harlan Greene, author of Why We Never Danced the Charleston, is always ready to mock what he calls the "deliberately Southern" Dixie dialectic that has prevailed since Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. Artist Thomas Sully—married to Susan Sully, author of Charleston Style: Then and Now—has made interesting studies of that "whole oppressive Southern agrarian movement." Dale Rosengarten, a sweetgrass-basket expert and director of the Jewish Heritage Collection at the College of Charleston, has the 411 on local politics and on Beth Elohim, the second-oldest synagogue in the United States and the birthplace of the American Reform movement in 1824. And Nichole Green, the young director of the Old Slave Mart Museum, set to reopen later this year, gives a feeling for what the institution will offer, guiding a visitor through displays of slave badges, planter's diaries, and other artifacts that capture the visceral horror of slavery. "Feel how heavy this is in your hand," she says, pulling out a 10-pound ball and chain from one case, "then imagine trying to run through underbrush with it wrapped around your ankle."

It's Sunday morning at St. Michael's Episcopal, the society church George Washington frequented; for years, worshippers came with their slaves, who sat in the upstairs gallery. The bells are clanging, and the crowd attending services in their Sunday best, with their sleepy golden children, make Norman Rockwell look like a realist. Just outside the church's pristine cemetery is the usual phalanx of Gullah women selling sweetgrass baskets, a craft perfected by the islanders off the coast. To the wellborn of a certain generation, Gullah is the language of maids and nannies—their dahs who used to quiet them with Shu yo mut (Shut your mouth)—but it's their language as well, an odd cross between a creolized Southern drawl, West Indian patois, and the emphatic barks of African dialects.

Listening to local preservation pioneer Mrs. Joseph Rutledge Young—the Gullah inflections of her voice skittering and swooping like a wayward marsh bird—is like eavesdropping on South Carolina history. She was raised way out in the country, on Edisto Island, in a circa-1700 spread with seven siblings, going to a one-room school in a horse-drawn buggy and sailing to town for shopping expeditions. A family-pew holder at St. Michael's, Young is something of a professional Charlestonian today: her perfect little 1798 "single house" on Meeting Street—one room wide, a formal entryway directly on the street, and a garden to the side—is often featured on walking tours.

Dressed in gray pants, black flats, and white socks ("I don't like to wear pants all day, though so many women do now"), she serves coffee in her cozy front parlor. Asked about the history of her family, she walks over to a glass case of memorabilia to bathe in the grace of history: "This is the hair of my husband's ancestors, made into wreaths—when there's black ribbon, it means they're dead." In Charleston, a resident might refer to a perfectly alive maiden aunt down the street as an ancestor. But Young, whose late husband's family goes back to signers of the Declaration of Independence, is also a forward-thinking sort, believing that the newcomers in Charleston have reenergized the city; in 1952, she was the first woman in town to become a licensed tour operator. "I'd drive visitors like Bob Hope and his wife around in my Oldsmobile convertible for five dollars an hour. For a dollar, Susan Pringle Frost, who lived in a 1760 Georgian house, the finest in America, would let you see her place. For four dollars you could stay overnight and be taken care of by all her maids, have your breakfast on a silver tray. Can you imagine that?"

One morning, when old-guard society had begun to feel claustrophobic in a badTennessee Williams kind of way, I aired myself out with a drive through the hardscrabble neighborhood known as the Neck, past the huge port facilities: Charleston has always been a city with muscles. On the outskirts of town, Magnolia Cemetery—all magnolias, live oaks, Spanish moss, and Confederate camp tombstones—is scented by the sharp earthiness of "pluff" mud (a local term applied to low-country marshland) along the banks of the Cooper River. Last year, 50,000 Civil War reenactors marched to Magnolia Cemetery to bury the crew members recovered from the recently discovered Hunley, a Confederate-era submarine. The city fired on Fort Sumter in 1861, but everyone talks about the "great unpleasantness" as if it happened last week.

Magnolia anchors a complex that includes the less scenic cemeteries of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, the Friendly Union Society, and a plot reserved for the Brown Fellowship Society. Together, they service every local religion and shade of skin color, in adjacent but distinctly separate facilities. In Charleston, the afterlife can be pretty much like life.

Along Highway 61, the grand old plantations on the Ashley River unfold like a diorama of dreams. The first stop is the Magnolia Plantation, built around 1676. This 500-acre estate may have been the earliest local tourist attraction, welcoming day-trippers shortly after the Civil War, and Fernanda Hastie and Taylor Drayton Nelson of the Drayton family still live there. The property is pure bucolic kitsch, complete with Biblical Gardens, alligators floating around in a gothic cypress swamp, petting zoos, trams, and antebellum slave quarters. Just down the highway is Drayton Hall, the oldest surviving example of Georgian-Palladian architecture in the U.S.: it remains as it was when John Drayton built it in 1738, without plumbing or electricity. Last on the plantation trail is Middleton Place, one of the most stunning estates in Charleston, with a precise formal garden, a butterfly-shaped lake, and hillsides draped in luxurious azaleas.

At certain moments, it seems as if the entire landscape of Charleston has been dusted in the dogwood blossoms that fall like snow, then sealed in one of those plastic dime-store paperweights: turned one way, the city is a simple proposition of pure beauty; upended, the scenery removed and the past factored into the equation, it means something darker.

Travel is often a quest for authenticity and real experiences that no one else has ever had, a quest that's virtually impossible in the modern era. The topography of the heart is mysterious, given to curious tributaries. A final stop in old Dixie gave me my electric memory of Charleston, the moment when I sensed that I had discovered new terrain.

The Confederate Home, which became a haven for Mothers, Widows, Orphans, and Daughters of Confederate Soldiers in 1867, is situated in a Victorian building at 62 Broad Street, in what is now the heart of the commercial district. Faded three-story piazzas (Charleston's word for its distinctive covered porches) surround a hushed courtyard planted with live oaks, camellias, and hyper-green grass, inhabited by a slew of cats: the residents, many of them widows who have fallen on hard times and have been there for decades, pop in and out of each other's apartments like helpful prairie dogs, embracing the art of letting go.

Josephine Humphreys, who is the unofficial figurehead of the literary set and adept at juggling the past and present, keeps an office at the Confederate Home. Beside a poster for the movie version of Rich in Love is a terminally Dixie family Christmas card from the fifties. With a honeyed Southern voice that could soothe nations, Humphreys laughs and points out the lies of history in the image: "That whole photograph, proper young ladies under the tree, was entirely staged—my mother borrowed vintage dresses from the museum."

And yet Charleston is still full of reverence for the entwined fates of all Charlestonians, the "concert of human lives," as Humphreys calls it. "When you grow up here, it's hard to get over the universal Charleston worry of what other people will think," she says. "The natives don't have many real places left, but the Confederate Home is the Charleston we all remember. It's just as real as it can be."

Tom Austin is a contributing editor for Travel + Leisure.

Battery Carriage House Inn Great Value

20 S. Battery; 800/775-5575 or 843/727-3100; www.batterycarriagehouse.com; doubles from $149.

Charleston Place Hotel

In the heart of the commercial district, and one of the city's larger hotels with 442

rooms.

205 Meeting St.; 800/611-5545 or 843/722-4900;www.charlestonplace.com; doubles from $319.

Inn at Middleton Place

A 52-room complex of modern design in a wooded area on the Ashley River, this hotel is part

of Middleton Place, a National Historic Landmark (details under What to Do).

4290 Ashley River Rd.; 800/543-4774 or 843/556-0500; www.theinnatmiddletonplace.com; doubles

from $139.

Palmer Home Bed & Breakfast

5 E. Battery; 888/723-1574 or 843/853-1574; www.palmerhomebb.com;doubles from $185.

Wentworth Mansion

An ornate Second Empirestyle mansion turned hotel.

149 Wentworth St.; 888/466-1886 or 843/853-1886; www.wentworthmansion.com; doubles from $335.

Charleston Grill

The renowned restaurant in the Charleston Place Hotel.

224 King St.; 843/577-4522; dinner for two $150.

Circa 1886

A highlight at the Wentworth Mansion.

149 Wentworth St.; 843/853-7828; dinner for two $100.

FIG (Food Is Good)

Featuring Mediterranean-American fare prepared with local ingredients.

232 Meeting St.; 843/805-5900; dinner for two $90.

Hominy Grill

Southern regional dishes with an ironic twist—like BLT's made with fried green tomatoes.

207 Rutledge Ave.; 843/937-0930; lunch for two $30.

Peninsula Grill

One of the most sophisticated restaurants in town.

112 N. Market St.; 843/723-0700; dinner for two $100.

Slightly North of Broad

A SoHo-style interior meets such low-country fare as shrimp and grits.

192 E. Bay St.; 843/723-3424; dinner for two $90.

B'zar

Edgy King Street outpost for trendy clothes and gear.

541 King St.; 843/579-2889.

ESD—Elizabeth Stuart Design

For furniture, handmade jewelry, vintage lighting fixtures, and regional cookbooks.

314 King St.; 843/577-6272.

Grady Ervin & Co.

A classic men's store with its own line of seersucker suits.

313 King St.; 843/722-1776.

Historic Charleston Reproductions Shop

Shop for distinctive local items such as linens inspired by the houses of Rainbow Row.

105 Broad St.; 843/723-8292; www.historiccharleston.org.

Magar Hatworks

The fantastic creations of couture milliner Leigh Magar have inspired a devoted cult following.

5571/2 King St.; 843/577-7740.

Moo Roo

Local designer Mary Norton's scarves, brooches, and handbags have attracted the likes of Sharon

Stone and Oprah Winfrey.

316 King St.; 843/724-1081.

Drayton Hall

A 1742 plantation on the Ashley River run by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

3380 Ashley River Rd.; 843/769-2600; www.draytonhall.org.

Edmondston-Alston House

One of the first houses built on the High Battery, open all year.

21 E. Battery; 843/722-7171; www.middletonplace.org.

Historic Charleston Foundation

Operates the Nathaniel Russell and Aiken-Rhett houses and sponsors the Festival of Houses

& Gardens every spring. Advance tickets available.

40 E. Bay St.; 843/723-1623; www.historiccharleston.org

Magnolia Plantation & Gardens

This 1676 spread has welcomed visitors since shortly after the end of the Civil War.

3550 Ashley River Rd.; 843/571-1266; www.magnoliaplantation.com.

Middleton Place

This 1741 historic plantation has an exquisite formal garden.

4300 Ashley River Rd.; 843/556-6020; www.middletonplace.org.

Old Slave Mart Museum

An intelligent museum in a former slave-trade sales room. Closed for renovation until late

2006.

6 Chalmers St.; 843/958-6467.

Preservation Society of Charleston

The society runs several historic properties and conducts tours of private homes in the fall.

Also has a great book and gift shop for all things Charleston.

147 King St.; 843/722-4630; www.preservationsociety.org.

Raval

A Barcelona-inspired wine-and-tapas bar: the back room has DJ's and a throbbing young crowd

on weekends.

453 King St.; 843/853-8466.

Torch Velvet Lounge

This hangout is all about atmosphere—a martini bar with velvet curtains, hookah pipes,

and bed-sized couches.

545 King St.;843/723-9333.