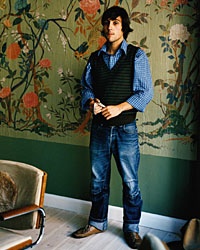

Martin Morrell Sune Rosforth, one of Copenhagen's top wine importers, at the restaurant Mitt.

Copenhagen has finally taken its place among Europe's capitals of cool—with inventive restaurants, edgy nightlife, and, as always, a preternaturally sharp eye for design. Now, if only the Danes could make room for the rest of us.

Martin Morrell Sune Rosforth, one of Copenhagen's top wine importers, at the restaurant Mitt.

Copenhagen has finally taken its place among Europe's capitals of cool—with inventive restaurants, edgy nightlife, and, as always, a preternaturally sharp eye for design. Now, if only the Danes could make room for the rest of us.

This isn't right, I think to myself, watching distressingly gorgeous couples sunbathe and sip vodka tonics while a DJ spins chilled-out Jamaican dub. Electrolysizedgods in Dolce & Gabbana swim trunks race across the silky sand to take leaps off the pier. Forget that it's only 50 degrees out and everyone is shirtless (except me, bundled in fleece). It's barely past noon on a Sunday, and a full-on beach party is under way in Copenhagen.

The scene has the marks of an exclusive, illegal rave: the location, on an abandoned wharf in Christianshavn; the crowd, which might occupy the first three rows at a fashion show; the absence of any kind of sign out front. You get the thrilling sense that should the cops suddenly crash through the fence, every bottle of Finlandia, every deck chair, every volleyball could be quickly tossed into the harbor, along with the 200 revelers. But this harborside beach club, known as Luftkastellet, is entirely legit—so much so that the crown prince of Denmark is a regular guest. To which I can still only say: This isn't right. This is patently unfair.

It's a feeling one often gets in Copenhagen, a city that exists primarily to inspire a deep regret among those cursed to live elsewhere. The Danes make the rest of us look like apes, and I'm not just talking about national health care or paternity leaves with full pay. This is a place where Wallpaper magazine is sold at the 7-Eleven, and where the clerks at 7-Eleven speak better English than most Americans. This is a town so reverent of aesthetics that a city ordinance bans cheap plastic café furniture—instead, sidewalks are lined with stainless-steel chairs and tables straight out of a design museum. Nobody steals them; everyone has much nicer ones at home. It's a city where even the airport has hardwood floors; a city where you may find yourself envious of a kindergartner's shockingly stylish shoes.

After one night in town your neck may ache from gawking. After twoyou'll be drunk on Arne Jacobsen cutlery and Wegner sofas. By the third you may resolve to sell every mundane thing you own and move here, perhaps claiming cultural asylum.

It wasn't always this way. I'd visited Copenhagen several times before and, like many friends, found it eminently civilized, jarringly clean, and pretty damn dull. This was the Copenhagen of Tivoli Gardens ("soulless, oversanitized," I'd scribbled in my journal years ago), sober-faced palaces ("attractive in a sexless, Sam Waterston sort of way"), stale smørrebrød with liver paste ("vile; notify Amnesty International"), and what I came to call the Little @#$%ing Mermaid. (I'm not alone in my antipathy, by the way: the statue has endured two beheadings and countless other humiliations. Last September, vandals with dynamite managed to blast the mermaid off her perch. She's back now, awaiting the next round of abuse.)

I had nothing against Scandinavia per se. I'm Swedish-American myself. Clean lines and bad food are in my blood. But Copenhagen back then struck me as full of people too civilized for their own good—too rich, too bland, and, excepting their furniture, decidedly unfunky. The music scene was just one example: only a few years ago Denmark's two principal exports were Aqua, of the grating novelty hit "Barbie Girl," and the supremely cheesy boy-band called Michael Learns to Rock. They were big in Taiwan. Enough said.

What happened?The city seems utterly rejuvenated.

It's no coincidence that the rest of the world is consumed by a fetish for all things Danish. Bands like Junior Senior (a superb dance-punk duo from Jutland) and the Raveonettes (who recorded an entire album of fuzzy garage rock in the key of B-flat) have finally caused Rolling Stone to forget about Iceland. Danish director Lars von Trier and his Dogma 95 cohorts are constantly being anointed as the future (or the end) of cinema. And from São Paulo to Saigon, you can't swing an artichoke lamp without hitting a nightclub or hotel that bows to Danish Modernism.

All this encouragement has helped Denmark's next generation make its mark. Take the young chefs of Copenhagen, who draw inspiration from no less daunting a model than Ferran Adrià of Spain's El Bulli. Adrià's outlandishly deconstructed dishes are to millennial cooking what Verner Panton's chair was to mid-century furniture; here his disciples are adding a Scandinavian twist and creating some of the zaniest food around (snail cappuccino?). Or take the entrepreneurs behind the brash new Hotel Skt. Petri—the first design-themed hotel to open in Copenhagen since 1960 (!), when Arne Jacobsen created the Royal. You can almost hear the rustling in attics across the city as Danish kids reclaim their grandparents' old Swan chairs and Finn Juhl coffee tables—perhaps to outfit some new boutique or café.

Perhaps all those Wallpaper spreads and São Paulo nightclubs reminded them of what Denmark was capable of. Whatever the motivation, Danes have got their groove back—and right now Copenhagen is arguably the coolest city in Europe.

Cool becomes the Danes. Nearly everyone you encounter is absurdly attractive, fiercely stylish, and possessed of an enviable, effortless grace. A Dane can glide about on a rickety granny bicycle with a bell on it and come off like Audrey Tautou. I rent one myself and pedal happily around town until I glimpse my reflection in a window, looking for all the world like a nerd on a bike with a bell on it.

When I first meet Sune Rosforth, he pulls up on a Long John cargo bicycle, and of course he makes the clumsy relic seem like Peter Fonda's chopper. Sune is one of Copenhagen's premier wine importers; as such, he's friendly with all the city's chefs. Through a mutual friend in New York, Sune has assigned himself the task of showing me "the city no foreigners know about, the top-underground city," whatever that means. Tonight he has scored us a table at First on the Right, Copenhagen's most exclusive restaurant—the bill must be paid when reservations are made; you're then informed, by post, when and where to show up. Only 16 fortunates are invited: nine courses, seven wine pairings, $165 per person. We're due at seven sharp.

So I hop on my girlie bike and follow Sune down the quiet residential streets behind Charlottenborg Palace. We stop outside a stately apartment building. Sune pushes a buzzer marked 1.th (først til højre, or "first floor, on the right"), and we ascend the old wooden staircase, to be greeted by a hostess in a vintage cocktail dress. She ushers us into a grandmotherly drawing room—flocked scarlet wallpaper, crystal chandelier, Royal Copenhagen china—where 14 other guests are chatting in small groups. A Milt Jackson record crackles on the antique turntable. The hostess circulates with sherry.

Suddenly two immense doors swing open to reveal a spare, brazenly modern dining room with seven tables. Beyond is a huge open kitchen, where two cooks are calmly preparing the hors d'oeuvres.

First on the Right is the creation of celebrity chef Mettesia Martinussen, who began hosting semiprivate dinner parties four years ago. Despite its low-to-nonexistent profile—publicity is mostly word-of-mouth—her place has been booked solid ever since.

Right now Martinussen is chopping fresh mint while her assistant tends to the roasted squab. We begin with a fragrant oyster-and-parsley soup, mascarpone-swathed crostini, and a zesty Terre del Sillabo Sauvignon Blanc. The mint turns up in a luscious grilled and stuffed octopus, followed by fried walleye with a rich purée of potato, smoky bacon, and peppery dill. A bit past the two-hour mark, the squab arrives, with chile-marinated haricots verts and Indian chapati bread. A salad interlude is followed by guinea hen, smartly dressed with green cabbage and apricot and paired with a brilliant Saumur-Champigny from Clos Rougeard. A cheese course, two desserts, and several glasses of Riesling later, it's nearly midnight and the guests have collapsed on the parlor sofas. Charades seems out of the question.

For the next 10 days I follow Sune and his friends around town, struck by how energized the city seems. It quickly becomes clear that a second, parallel city exists, a few steps beyond the familiar one. Just when Copenhagen seems too monied, too refined—too monolithically Copenhagen—you stumble on, say, a beach party on an abandoned wharf. And in outlying, formerly dingy enclaves like Vesterbro, Nørrebro, and Islandsbrygge, you now find the most-talked-about shops, cafés, and nightclubs, as well as the grit and bohemian flavor absent in the city center.

From my companions' excited descriptions of scuzzy sailors' haunts and graffitied apartment blocks, I expect these boroughs to be forbidding, ramshackle slums. But in Copenhagen scuzz is a relative term. Even the seedy districts turn out to be well-supplied with handsome Neoclassical façades, handsome storefronts, and still more handsome people. Who knows, maybe they're junkies. One can only hope.

Vesterbro, in particular, is a bastion of the young and fashionable and is rapidly gentrifying. Of course, gentrification is a moot term as well in Denmark; the whole damn country was gentrified decades ago. But Vesterbro is in the midst of a transformation from what was once the domain of brothels and slaughterhouses. On the cobblestoned streets around Halmtorvet Square, you'll still spot some "topløs bars," but you're just as apt to find a Birger-Christensen sample sale in a newly converted cattle market, or a jazz bar holed up in a disused warehouse. Last spring a trio of cafés took up residence in the Carlton Hotel, an old hooker hangout that had been closed for a decade. Vesterbro also has a large number of new restaurants: I had one of the best Vietnamese meals of my life at Lê Lê, a sun-floodeddining room run by four siblings from Saigon. A mixed crowd—black, Indian, Southeast Asian, Danish—sat at mismatched junk-shop tables slurping basil-spiked pho. There wasn't a single Functionalist chair in sight. For the first time in all my visits, Copenhagen didn't look like Copenhagen.

Just west of downtown lies Nørrebro, a neighborhood that was long synonymous with ethnic riots and urban blight. Back in the eighties, when it was seen by the (white) well-to-do as a sort of Danish South Bronx, Nørrebro was the epicenter of a transparently racist "clean-up" campaign. And here it must be said that xenophobia is the Achilles' heel of this otherwise admirably progressive country—a distressing flip side to the Danes' boisterous flag-waving. Though Denmark has a relatively small foreign-born population (about 7 percent) and one of the lowest immigration rates in Europe, it has lately been plagued by the rise of far-right groups such as the Dansk Folkeparti (Danish People's Party). The DF's anti-immigrant agenda—fueled by 9/11 and fears of global terrorism—met with alarmingly strong support in the 2001 elections (in spite of fierce resistance from forward-thinking Danes). Denmark's struggles with racism, with its historic insularity, and with the demands of the welfare state and the burdens of relative prosperity, have come to dominate national politics. (This same xenophobia was arguably a factor in voters' rejection of the euro in 2000.)

At the same time, the incursions by the extreme right have galvanized Denmark's more progressive and tolerant youth, for whom Nørrebro has functioned as a sort of lefty HQ. Here's where you find the studio of the Superflex art collective, which, in response to the immigration debate, created a famous line of T-shirts with the slogan FOREIGNERS, PLEASE DON'T LEAVE US ALONE WITH THE DANES.

Nørrebro has endured as the city's most racially diverse quarter—though it, too, is now a burgeoning enclave for the city's edgier beau monde. Amid the jumble of streets radiating out from St. Hans Square, art-supply stores and vintage-clothing shops share blocks with Persian bakeries and Moroccan fruit vendors. At Kate's Joint, a dingy hangout serving cheap Middle Eastern food, the clientele ranges from bearded Palestinians to towheaded skate-punks. On Blagardsgade, fliers for protest rallies are tacked up alongside f*** usa and NO WAR graffiti. Like Vesterbro, Nørrebro is a world apart from the Copenhagen I once knew—the stoic, refined (and very white) city a mile away.

Such is the geography of this strange, tiny town. Copenhagen is compact enough that every square foot is continually being reclaimed and reinvented. An apartment becomes a five-star restaurant; a cattle market becomes a venue for a fashion show; a derelict wharf becomes a Miami-style beach club. Surprises lurk around every corner. Walk a block east from the shawarma joints and currency-exchange booths around Rådhuspladsen and you emerge onto a tranquil lane (Magstræde) that hasn't been updated in centuries. Wander off the tony Strøget pedestrian strip, with its couture shops and design emporiums, and you're suddenly knee-deep in the funky Pisserenden district, where Japanese anime shops cater to boho students and accordion music drifts out of a cellar bar. And in Tivoli Gardens—that Disneyfied playground—you now find one of the most progressive restaurants in northern Europe.

Last summer, acclaimed chef Paul Cunningham, a British expat, took over Tivoli's sparkling Glassalen, a glass-enclosed folly designed by Poul Henningsen in 1946. Tivoli already holds some 40 restaurants, but this one is an entirely new animal: Did you ever expect to be served vanilla-scented langoustine, afloat in a cup of puréed artichoke and mascarpone—at an amusement park?

Cunningham claims he was too self-conscious to name the restaurant after himself: "Calling it Paul would have been terribly arrogant, no?" Instead he named it The Paul. "See," he says, "now it has that second element—'the'—to give it some distance from myself." The Englishman admits he's perplexed by the innate modesty of the Danes. "People here don't like to make a big deal of themselves," he says. "But why aim for four stars when you want five?"

It certainly takes chutzpah to decorate your restaurant with framed menus from Gordon Ramsay and Manoir aux Quat' Saisons. Occupying pride of place on the chef's table is Ferran Adrià's massive El Bulli cookbook, glowing like a Gutenberg Bible. Cunningham is effusive about Adrià's mad-scientist alchemy: "How can you not be wowed by him?I was at El Bulli a few months ago and he served us 'foam of ash.' We were literally eating smoke! Cooking is about theater. Look out the windows—we're next door to a magic show! We need to entertain people."

It's hard not to be entertained by the revolution under way in Copenhagen's kitchens. Danish chefs are hard at play, reconceiving every ingredient with outrageous results. Wild garlic takes the form of a gelée, escargots are whipped into foam, parsley emerges as a grainy sorbet. It's only a matter of time before smørrebrød with liver paste is rendered into a pungent vapor and served through an oxygen mask. But let's not give them any ideas.

Later that week Sune and I pedal over to K Bar, a sultry den specializing in cocktails, still a rarity in lager-loving Copenhagen. It's here that I meet René Redzepi, another of the city's preeminent chefs. René looks far too trim to be a cook—a blond Paul Rudd. He honed his craft at El Bulli and at French Laundry, and now he's heading up the restaurant at the just-opened North Atlantic House cultural center, across the harbor in Christianshavn. Everyone in town has been raving about the complex, so the next afternoon I bike over to take a look.

North Atlantic House was carved out of an 18th-century gray-brick warehouse, replete with pinewood beams and a pitched red-tiled roof. The space now contains the representatives of Iceland, Greenland, and the Faeroe Islands, along with halls devoted to Nordic art and culture. That theme dominates the menu at Noma, where René is shirking olive oil and sun-dried tomatoes in favor of sugar beets and Greenland musk ox (quite tasty, incidentally).

It's stunning, and all the more appealing for its de-fiantly retro setting. Just when you couldn't take another hypermodern façade— like the ruthlessly minimalist Black Diamond library, onthe waterfront—North Atlantic House reminds you of what Copenhagen was before form followed function: a city of brick, cobblestones, and wind-scarred wood, a maritime town of rusty piers and narrow canals.

In the old quarter of Christianshavn, with its canal- side cafés, pastel edifices, and retrofitted houseboats, that era endures. Here, and in the nearby districts along the harbor, Copenhagen is rediscovering the glories of its waterfront. The much anticipated Copenhagen Opera House will open next year on the former naval base at Holmen. Condos and high-tech firms are already ensconced in old U-boat assembly plants. In Islandsbrygge, an industrial area laced with freight rails and ringed by abandoned docks, galleries are opening, and families are moving into neglected lofts. The atmosphere recalls TriBeCa in the mid eighties.

But the real action is on (and in) the water itself. As soon as the temperature climbs, in May, out come the café tables, the heat lamps, the Jacobsen ashtrays; off go the woolen coats and on go the swim trunks. Luftkastellet is, it turns out, only one of several beach clubs to spring up lately around town—some legal, some not so legal. Some might not last the season. Some will simply move down the harbor to another dilapidated wharf.

There's always another wharf, and a crowd to please. Sand is shipped in from Jutland, pétanque courts are laid out, sound systems set up, and suddenly all of Copenhagen is jumping into the harbor, blissed out and beautiful under the hazy northern sun.

No, this just isn't right at all.

PETER JON LINDBERG is an editor-at-large for Travel + Leisure.

WHERE TO STAY

Hotel Skt. Petri

Opened last July in a 1928 Functionalist building, this swank design hotel is splashed with vivid colors and outfitted with minimalist Scandinavian furnishings. Balconies overlook red-tiled roofs and quiet churchyards. DOUBLES FROM $400. 22 KRYSTALGADE; 45-33/459-800; www.hotelsktpetri.com

Radisson SAS Royal

Arne Jacobsen designed everything in his 1960 masterpiece, from the flatware to the 22-story tower itself. DOUBLES FROM $250. 1 HAMMERICHSGADE; 800/333-3333 OR 45-33/426-000; www.radisson.com/copenhagendk_royal

WHERE TO EAT

1.TH (First on the Right)

DINNER FOR TWO $330. 9 HERLUF TROLLESGADE; 45-33/935-770

Noma

DINNER FOR TWO $125. AT NORTH ATLANTIC HOUSE (NORDATLANTENS BRYGGE), 93 STRANDGADE; 45-32/963-297; www.noma.dk

The Paul

DINNER FOR TWO $200. GLASSALEN, TIVOLI GARDENS, 3 VESTERBROGADE; 45-33/750-775; www.thepaul.dk

Lê Lê

DINNER FOR TWO $80. 56 VESTERBROGADE; 45-33/227-135

Ensemble

This ambitious yet unpretentious newcomer had been open barely eight months when it earned its first Michelin star. DINNER FOR TWO $170. 11 TORDENSKJOLDSGADE; 45-33/113-352; www.restaurantensemble.dk

TyvenKokkenHansKoneOgHendesElsker

In a 1733 building, a candlelit dining room is the setting for unexpectedly progressive food: parsley foam with grilled pike perch; masterfully poached oysters from Jutland. DINNER FOR TWO $190. 16 MAGSTRÆDE; 45-33/161-292;; www.tyven.dk

Restaurant Aura

A sleek Mediterranean restaurant-lounge serving tapas-style tasting plates. The sexy crowd stays late into the night for dessert: a chilled lavender soup, perhaps, or grappa-infused green apples. DINNER FOR TWO $110. 4 RÅDHUSSTRÆDE; 45-33/365-060; www.restaurantaura.dk

Emmerys

The best bread in town can be found at this bakery and café near Nyhavn, and at branches in Vesterbro and Nørrebro. 21 STORE STRANDSTRÆDE; 45-33/930-133; www.emmerys.dk

Mitt

New restaurant in Nørrebro. ÆGIRSGADE 46 AB; 45-39/671-512

AFTER DARK

K Bar

20 VED STRANDEN; 45-33/919-222

Zoo Bar

Stop by this trendy watering hole after a day of couture shopping. 7 KRONPRINSENSGADE; 45-33/156-869

Fyrskibet

Escape the crowds on Nyhavn Canal by climbing aboard this century-old lightship—for a drink. 151 NYHAVN KAJPLADS; 45-33/111-933

Barstarten

By day it's a café; at night, DJ's tear it up while patrons down cactus cider and dance on the tables. 1 KAPELVEJ; 45-35/241-100

Panton Lounge

Inside the landmark Langelinie Pavillonen building—steps from the Little Mermaid—this ultra-chic space has become the place for fashion shows andart events (call or go on-line for schedules). 1 LANGELINIE; 45-33/121-214; www.langelinie.dk

SHOPPING

Illums Bolighus

Four floors of the most devastatingly handsome, unabashedly modern furniture, tableware, lamps, and kitchen accessories. 10 AMAGERTORV; 45-33/141-941; www.royalshopping.com

Paustian

Way out near the wharves of Østerbro lies this terrific furniture showroom, whose stock includes Eames, Aalto, and all of Denmark's leading lights. Bonus: The warehouse itself was designed by Jørn Utzon, creator of the Sydney Opera House. 2 KALKBRÆNDERILØBSKAJ; 45-39/166-565; www.paustian.dk

Casa Shop

An exceptionally well curated alternative to Illums Bolighus, and not so daunting or high-priced. 2 STORE REGNEGADE; 45-33/327-041; www.casagroup.com

Storm

A spacious, modern show-room houses designs by Comme des Garçons, Dries van Noten, and Danish labels like Baum und Pferdgarten. 1 STORE REGNEGADE; 45-33/930-014; www.stormfashion.dk

Könrøg

A stellar women's clothing and accessories shop in Pisserenden, run as a consortium by six designers. 11 HYSKENSTRÆDET; 45-33/327-877; www.koenroeg.dk

Munthe Plus Simonsen

One of the city's more playful designers, and a reputed favorite of Danish model Helena Christensen. 10 GRØNNEGADE; 45-33/320-012; www.muntheplussimonsen.dk

Bruuns Bazaar

Clean, classic designs by the two Bruun brothers on posh Kronprinsensgade. 8-9 KRONPRINSENSGADE; 45-33/321-999; www.bruunsbazaar.com

BEACH CLUBS

Luftkastellet

100 STRANDGADE; 45-70/262-624; www.luftkastellet.dk

Halvandet

325 REFSHALEVEJ; 45-70/270-296

Pappa Hotel

19 KALVEBOD PLADSVEJ; 45-33/112-908; www.pappahotel.dk