Dook

Forget bricks and mortar—tents are the latest design trend for resorts. T+L canvasses the globe to uncover the best

Dook

Forget bricks and mortar—tents are the latest design trend for resorts. T+L canvasses the globe to uncover the best

Forget the frumpy, olive-drab tents of your childhood. A new breed of oversized tents is being pitched at ecotourism sites and luxury resorts around the world. Whether done in Rajasthani opulence or hippie chic, they are the little black dresses of the soft-adventure market—easily accessorized to fit any mood. Spurred on by large-scale examples of tented architecture, such as Denver's airport, London's Millennium Dome, and the Aspen Music Festival Tent, as well as innovations in tensile construction, tented tourism is experiencing a renaissance.

Tents have long been steeped in drama, as they loom over circuses, weddings, and bazaars. "They have a slightly subversive adventurousness," says architect David Rockwell. "They remind me of being a kid and draping fabrics bed-to-bed." But tents also hold an undeniable back-to-basics appeal, embodying our ambivalence toward shelter. On a rainy night, they reassure us that we are protected; on a fine day, with a gentle breeze blowing through, they suggest that we can, in fact, return to some idealized version of nature. As interior designer Jeffrey Bilhuber, who has built many tented garden rooms, points out: "Even if just the roof is tented, when you can see light, a shadow moving across the ceiling, the billowing of fabric, then you've connected."

According to Roger White, a historian at the Smithsonian, a similar boom in tent-travel—auto-camping—occurred in the early 1920's. "Life was becoming more machine-like," says White. And so people bought tents, packed up their cars, and hit the road. Our high-tech lives seem to be having the same effect. "We're slipping deeper and deeper into the digital abyss," says architect Philip White, who designed the tents at Molokai Ranch in Hawaii. "The virtual world is becoming more of our reality, so being outside is that much more meaningful and emotional."

A few years ago, I had such an experience during a weeklong stay in one of Stanley Selengut's Concordia Eco-Tents on St. John. My breeze-cooled, soft-sided bungalow with 270-degree ocean view featured a handmade, foldout futon bed; a vaguely kitchen-like cooking arrangement; and a private bath-tent with a dribbly, solar-heated shower that I had to pump myself. The nervously anticipated compost toilet made me feel noble each time I used it. Because I often had to get up during the night to close the tent flaps against the rain, I slept in shorter, more irregular intervals than at home. It was still the most relaxing vacation I'd ever had.

Tented camps, if they are thoughtfully planned, can have a relatively low ecological impact. Selengut made this the norm by building his camps on post-supported platforms, which eliminated the need for bulldozers to level sites. Since their debut in 1976, with Maho Bay, his "eco-tents" have caught the fancy of environmentally aware tourists. The past few years have brought several new resorts that reflect Selengut's influence: Costanoa in California, the Molokai Ranch & Lodge in Hawaii, and, just five months ago, Daniel's Head Village in Bermuda.

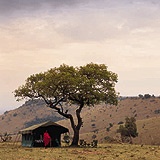

At the same time, demand has grown for a more lavish type of tent, combining theatrical design with the comforts of top-tier resorts. Such tents are popping up all over the world, but their true home is on safari in Africa. "In the old days, a huge caravan of staff went ahead of you," says South African decorator Graham Viney, who is responsible for Orient-Express Hotels' Gametrackers camps in Botswana. "By the time you reached camp, they would have pitched the tents, started a fire, and baked scones; you'd have tea before dressing for dinner. They would create a little circle of civilization, in the pool of light cast by a paraffin lamp."

Fueled by competition among safari destinations, that circle of civilization has become increasingly elaborate. Kichwa Tembo Bateleur Camp, a tented lodge that opened last summer in Kenya's Masai Mara game reserve, exemplifies this expansiveness. Bateleur's richly appointed, canvas-walled salon is a picture-perfect safari-style set piece. Stylishly cluttered with bowls of ostrich eggs, vases of splayed porcupine quills, and silver-framed photos, it gives the illusion that the master of this camp must be one of Theodore Roosevelt's more flamboyant descendants.

Extravagant tents have recently appeared outside the safari world, too. The pioneer was Amanresorts' Amanwana, which opened on Moyo Island, Indonesia, in 1993. Its spacious, tented bungalows, designed by Jean-Michel Gathy, integrate solid walls with fabric roofs. When Gathy married the look of a tent to a hard-built foundation, he paved the way for even more upscale tent amenities, such as air-conditioning and twin-sink bathrooms.

Employing a similar model, Al Maha, in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, expanded on the traditional design of bedouin encampments. By the time the resort opened in 1999, the air-conditioned, tent-roofed suites, each with a private swimming pool, had been outfitted with Persian rugs, upholstered settees covered with pillows, and stone-tiled waterfall showers.

At Rajvilas, in Jaipur, India, the sumptuous, tented accommodations were patterned after the hunting camps of the maharajahs. Vikram Oberoi, son of the hotel's creator, P.R.S. Oberoi, explains their provenance: "Among the royal families of Rajasthan and Jaipur, there was always a tradition of game hunting. We wanted to impart the feeling of what royalty would experience." To that end, the fabric ceilings are block-printed by hand and stitched with gold thread. Hardwood campaign chests give the impression of a movable camp, but a hidden air-conditioning system suggests permanence.

The Rajvilas tents were so enthusiastically received that the Oberoi company is opening a second tent hotel this summer, at the edge of Jaipur's Ranthambore National Park, where wild tigers roam. Meanwhile, safari outfitter Abercrombie & Kent is planning to bring elements of its top-tier African service to its American river-rafting trips. In addition, tented camps have been proposed for sites in Oahu and Catalina Island in California.

Last spring and summer I visited several tent camps in quick succession, hoping to get to the root of their appeal. I started with the oldest I could find: 100-year-old Curry Village in Yosemite National Park. Its no-frills tents, with common bathhouses, are set in tightly spaced rows in a scenic patch of the Yosemite Valley. Much of their allure comes from their price, which is absurdly low. But when a blizzard hit and my tent was buried, the bargain didn't look quite as good. Later, after the snow stopped and the moon slipped from behind the clouds, I listened to the roar of the nearby waterfalls and watched the tents light up like party lanterns. Mine smelled gassy from the heater, but it was warm. As I lay in bed reading, I became unexpectedly enamored of my flimsy shelter. I had no doors to close against the storm, just flaps. It was ridiculous—and thrilling.

The weather was better at Costanoa, a tented camp just south of Pescadero, California, that opened in 1999. As in Curry Village, clusters of tents share bath facilities, but Costanoa is of the new breed of tented camps, and so is better appointed. My tent, one of the camp's best, had a queen-size bead-board bed and colorful accessories, including sunflower-yellow throw pillows. The overall effect was reminiscent of Pottery Barn in its genteel rusticity.

Costanoa was where I began to understand the tent "experience." Hikers and other hardy outdoorsy folks actually go camping. We city dwellers, with our bad knees, heightened sun sensitivity, and fears that sleeping on the ground will mean that we are homeless, have tent experiences. The great thing about a tent experience is that nature can be enjoyed while reclining. As I lounged atop my puffy duvet, there was the pretty green world outside. I could bathe in the light of it, smell it, hear it, and feel it blowing across my face, but didn't actually have to be in it, with the bugs and the dirt.

At Molokai Ranch & Lodge's 22-acre Kaupoa Beach Camp in Hawaii, architect Philip White's tents strike an ideal balance between good intentions (composting toilets, solar-powered lights) and aesthetics (cowboy-inspired interiors by designer Mary Philpotts). Plywood floors, painted red, are covered with palm-frond mats. Blue-and-green fleece blankets cover wooden beds. Bathrooms remain open to the sky; their walls are of rough-hewn Douglas fir and galvanized steel. Each tent has a large lanai with cushioned lounge chairs. I saw more shooting stars in one night at Molokai than I had all the previous nights of my life combined.

I didn't see stars at Daniel's Head Village, but only because the ambitious new tented camp in Bermuda wasn't quite ready for guests. Instead of sleeping there, I spent an afternoon lounging in the camp's prototype tent. It was furnished much like a hotel room, with a firm bed and gold-framed artwork. Of all the tents I visited, it seemed the most solidly constructed—designed, I was told, to withstand winds of up to 110 miles per hour. And because Bermuda can be chilly in winter, glazed windows had been installed. The resulting solidity, though reassuring, reduces the exhilaration that comes from open-air living. That said, when a howling rainstorm blew in during my visit, I was grateful for the sturdy construction.

While my heart belongs to the rustic camps, during a trip to Kenya's Olonana I discovered that I could wholeheartedly enjoy a fling with tented extravagance. My quarters at Abercrombie & Kent's top-of-the-line compound were positively cocoon-like. The room was big enough for two queen beds and decorated in a style you might call Masai-modern: wrought-iron lamps with burlap shades, cotton rugs in geometric patterns of rust, black, and tan, and bedside tables trimmed with cowhide. In the large, stone-clad bathroom, shampoos were presented in hand-turned clay carafes. Throughout, the hardwood floors felt as smooth as polished glass under my bare feet. An expanse of screen looked out to the Mara River, where hippos floated by, twitching their ears and spraying water from their noses.

Many stagehands were responsible for making the drama that was my stay at Olonana go smoothly, from the steward who brought me freshly baked treats, to the kitchen staff that staged a wilderness cocktail hour for me one evening, complete with cut-glass stemware, a bonfire, and live music. It sometimes seemed an entire Broadway production had been dropped into the bush, with me as its Lion King.

Al Maha Dubai, United Arab Emirates; 971-4/303-4222, fax 971-4/339-9696; www.al-maha.com; tented suites from $900.

Amanwana Moyo Island, Indonesia; 800/447-7462, fax 62-371/22288; www.amanresorts.com; tents from $675, double.

Concordia Eco-Tents St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands; 800/392-9004, fax 212/ 861-6210; www.mahobay.com; tents from $85, double; $15 for each additional.

Costanoa 2001 Rossi Rd. (at Hwy. 1), Pescadero, Calif.; 800/738-7477, fax 650/879-2275; www.costanoa.com; from $30 for no-frills, bring-your-own-bedding to $240 for deluxe, fully furnished tents.

Curry Village Yosemite National Park, Calif.; 559/252-4848; www.yosemitepark.com; tents from $59.

Daniel's Head Village 4 Daniel's Head Lane, Sandys, Bermuda; 877/418-1723, fax 441/234-4270; www.danielsheadvillage.com; from $115 for a water-view tent in winter to $250 for an over-water tent in summer.

Gametrackers Botswana; 800/421-8907, fax 818/507-5802; www.orient-expresshotels.com; 7-night package $3,695 per person.

Kichwa Tembo Bateleur Camp Masai Mara National Reserve, Kenya; 271-1/809-4300, fax 271-1/809-4400; www.ccafrica.com; all-inclusive tents from $400 per person, per night; safari packages available.

Olonana 800/323-7308, fax 630/954-3324; www.abercrombiekent.com; Wings over Kenya group safaris cost $3,935—$4,600 per person and include a three-night stay at Olonana.

Molokai Ranch & Lodge Maunaloa Hwy., Molokai, Hawaii; 877/726-4656, fax 808/521-1606; www.molokai-ranch.com; Kaupoa Beach tents from $215.

Rajvilas Goner Rd., Jaipur, India; 800/562-3764, fax 91-141/680-202; www.oberoihotels.com; tent-roofed suites from $375.