Author Helena Attlee first experienced the lure of lemons on a trip to Italy, at the age of 18. “We were somewhere near Ventimiglia on the Italian Riviera,” she writes on the opening page of her cultural history of citrus fruit, The Land Where Lemons Grow (Countryman Press in the U.S.; Penguin in the U.K.). “And there were lemons growing beside the station platform, their dark leaves and bright fruit set against a backdrop of nothing but sea. I never forgot those trees, or the way they charged the landscape around them, making it seem intensely foreign to my very English eye.”

Twelve years later, she and her photographer husband were commissioned to write a book about Italian gardens and travelled around Italy, with their three-month-old daughter and a tent. “It was then that I began noticing the ornamental citrus fruits, planted everywhere in pots—and how strange they were,” she says. “The fruits might be stripy, or shaped like hands; many had once been part of 16th century curiosity collections across Italy.”

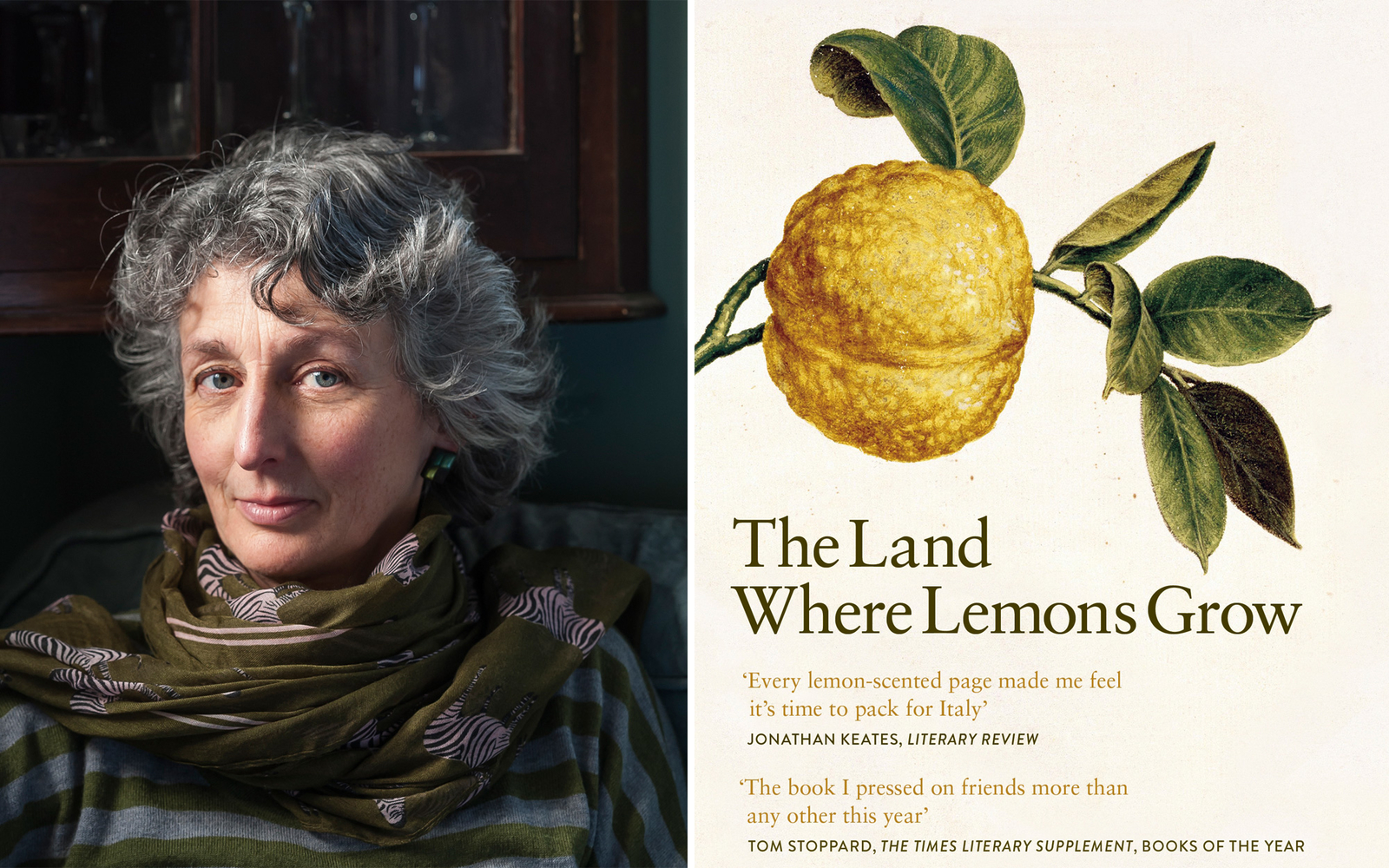

She published the Lemons book in 2014; subtitled “The story of Italy and its citrus fruit,” it’s a potent mix of history, botany, horticulture, art, first person travelogue, and recipes, and has won a clutch of awards—including the U.K. Guild of Food Writers Food Book of the Year, 2015. Attlee talked to T+L about her favourite citrus-related discoveries in Italy.

Initially, there were only three kinds of citrus fruit in the world: citrons from Assam in Northern India, mandarins from China, and pomelos (a grapefruit-like fruit) from Malaysia. But citrus is strange in that it will cross-pollinate with any other kind of citrus fruit—and today’s lemons, oranges, are all hybrids of these three ancient varieties. The first lemons and bitter oranges probably reached Sicily with the Arab settlements in 8 AD.

Calabria. A tiny stretch of coastline around Villa San Giovanni and Reggio Calabria produces the world’s best bergamot (a round, green, rough-skinned fruit), essential to the perfume industry; whilst the northern area between Tortora and Belvedere Marittima is famous for Diamante citrons, a large yellow fruit sacred to Lubavitcher Jews, to whom it’s know as esrog.

In Reggio Calabria, I recommend visiting the Museo del Bergamotto, which has a bergamot-themed restaurant; there’s also a tasting center in nearby Villa San Giovanni. I also suggest going to the seaside citron-growing towns of Santa Maria del Cedro and Scalea, for a wander around the citrus groves.

Villa Medicea di Castello, near Florence. The gardens contain part of the original Medici citrus collection, with a genetic line that goes back hundreds of years. During World War I, the limonaia became a hospital, and the trees were left out in the cold. But curator Paolo Galeotti has spent years restoring them. Viewing the plants is like looking at a picture gallery; each tree bears completely different kinds of fruit.

Most of the citrus fruit grown in Italy is naturally organic, and is, of course, more flavorsome. But the government stopped protecting the industry, so today, Italian fruit faces serious competition from countries that pay workers less.

Secondly, a disease appropriately called tristeza—a virus transmitted by an aphid, that causes dieback—has decimated the lemon and orange groves in the south. But growers are now replacing diseased trees with a more resistant kind of root stock, so the industry seems to be recovering.

Single-varietal marmalade from Marchesi di San Giuliano, in Sicily. Tiny bottles of Cedrello liqueur, made from citrons in the town of Santa Maria del Cedro, Calabria. Candied orange peel dipped in chocolate, which you can find, for example, at Giovanni Galli in Milan. Candied chinotto (a round, orange fruit), often preserved when green in Maraschino liqueur from Savona, Liguria. The taste is extraordinary.