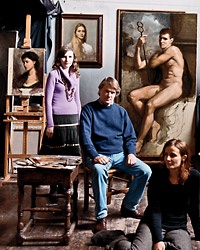

Andrea Fazzari Charles Cecil (center) surrounded by students and a model, in his drawing studio in Florence's Oltrarno district.

Andrea Fazzari Charles Cecil (center) surrounded by students and a model, in his drawing studio in Florence's Oltrarno district.

Florence produced some of the world's greatest painters—from Masaccio to Michelangelo. Charles Maclean enrolls in one of its best-known drawing schools and discovers that it's never too late to become a Renaissance man.

Across the river, in the blue-collar Oltrarno district, where for centuries the art of Florence has been made and mended in neighborhood workshops and bottegas, I enter with some trepidation the oldest operating atelier in the city: Charles H. Cecil Studios. In continuous use as a drawing studio since the early 19th century, the Cecil Studios is also one of the last schools of fine art in the world that teaches pupils how to draw like the Renaissance masters.

The volatile fug of oils and turpentine thickens as I climb the steep marble stairs from the street. A pretty woman in Levi's and a dark turtleneck drifts by with an armful of small mirrors. "Weren't we expecting you... yesterday?" she asks vaguely in an English accent and with a distracted manner reminiscent of Warhol Factory personnel circa 1979. "He's working. I'll see if he can be interrupted."

She leads me through a complex of rooms lit by high windows; we're in the roof space of a former church. Blackout curtains are pulled aside, and Charles Cecil, interrupted, emerges, palette in hand. A tall fiftysomething man in faded denim, with strong chiseled features and longish hair, he looks like everyone's idea of a master painter. Gravely exuberant (I half expect the shoulder clasp with which Charlton Heston greeted acolytes in The Agony and the Ecstasy), he welcomes me to the city of Michelangelo. On a whirlwind tour of the atelier—the cast room, the sculpture room, the gipsoteca, and the drawing studio where I will be joining the first-year life class—Cecil expounds on the importance of upholding the tradition of naturalistic figure painting. Cecil, who studied at Yale and apprenticed with two American painters, opened the school in 1983. He shows me some of his own works in progress. I'm struck by a Titianesque Deposition from the Cross and a small delicate portrait of Ann Witheridge, the woman in Levi's, who turns out to be one of Cecil's chief assistants.

Besides learning how to draw, I've come to Florence to fulfill another delayed ambition. Though my father grew up here, I have never stayed long enough to get to know the city. I want to discover the Florence that I dreamed about as a child, raised in Scotland on tales of the Medici and reproductions of Benozzo Gozzoli, whose Procession of the Magi hung above my bed. I want to see the houses where my grandparents Charlie and Gladys lived as part of a raffish, once glamorous Anglo-Florentine colony.

In the courtyard of a grand apartment building on Lungarno Amerigo Vespucci, their last address, the portiere bellows over the intercom that there's no one here called Maclean. When I explain that I'm talking about 40 years ago, she hangs up. Back at my hotel on nearby Via Montebello, I order a cup of tea with a nostalgic brand name, Sir Winston English Blend, that offers, absurdly, a soothing, if remote, connection to Charlie and Gladys. It was his lifelong friendship with Churchill that helped secure my grandfather, who had been disabled by wounds received at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, the post of British consul to Florence.

Following the daily route he took to the consulate, I wander up Via del Proconsolo to look at the sculptures in the Bargello museum. Onto the crowded sidewalk I project a Merchant-Ivory vision of Charlie: straw hat, white suit, glint of a gold watch chain, walking with the help of a black malacca cane. A simple, soldierly character, he seems an unlikely gamekeeper for Florence's famously louche expat community.

In an upper room of the Bargello, I stand spellbound by Andrea Della Robbia's glazedterra-cotta portrait of a young noblewoman. Her hair, scraped back into spiky plaits and adorned with rows of pearls, reminds me alternately of Beatrice's (I'm re-reading Dante's La vita nuova) and the retro-punk look favored by my teenage daughters. Her face, demurely reflecting the love it must have inspired, enchants me. I want to know who she was and whether her likeness in clay began life as a drawing... but I'm already late for my first class.

I pass through the gipsoteca—a silo-like space that soars 90 feet high—and enter the studio. There's a disquieting moment as I realize I'm the only male in a room full of women, one of them nude. Nobody else seems to notice or care. Throughout the studio, kept steamy as a sauna for the life model's comfort, there is a hushed concentration.

With Ann's help, I set up my easel, and get to work. I learn the sight-size method—standing back from the easel, I visually fit the model onto the paper, using a piece of string as a plumb (perpendicular) line to take measurements. In the beginning, I find working on a vertical plane a challenge. (Though I've painted and drawn before, this is the first time I've used an easel.) But I soon get the hang of holding a pencil like a brush, walking back and forth between the plumb line position and the easel, making little marks on the paper that grow into a forest of coordinates as the image slowly takes shape.

The moment of truth comes when I look back through a mirror at what I've done. Maybe I stopped measuring and started connecting the dots too soon, but the mirror—il vero maestro, as Leonardo da Vinci called it—doesn't lie: the mistakes are glaring. I've no choice but to erase and start over.

For the next three hours I remain lost to the world. When the session ends, the studio empties fast. Leaving strips of tape on the floor to mark easel positions, the students (mostly twentysomething Brits and Americans) gossip, roll cigarettes, and make plans on their cell phones as they clatter down the hall and out into the street. They seem at home here, enjoying the safe, bohemian-lite way of life that has long been part of Florence's allure. It was not so different in Charlie and Gladys's day, when the insider status assumed by foreign residents was founded upon a sentimental view of Florence as an art-lover's protectorate.

It feels like early spring as I walk up the Viale Galileo Galilei. With the help of an old map, I find the Villa Arrighetti, where my grandparents lived from 1922 to 1948. The handsome building, now owned by a religious order, has been renamed Villa Agape and turned into a spiritual retreat. The grounds—an avenue of cypresses, a sloping grass path, olive orchards—are exactly how I imagined they would be.

At the bottom of the garden, I discover the iron gates to the Viale, where in May 1938 Gladys stood and watched Hitler and Mussolini drive by in a convertible on their way to San Miniato. She refused to wave; instead, she turned to her companion, Miss Good, and said, "Darling, if only we had a bomb. Imagine... "

The war, when it came, stranded my grandparents in Switzerland, where they were interned. The Villa Arrighetti was closed, and their few valuable possessions were taken into safekeeping by their friends the Fioravantis, an unconventional family who enjoyed dancing Highland reels and kept a crocodile as a garden pet. The Fioravantis hid the Maclean candlesticks from the Nazis—just as many villa owners bravely concealed the great art treasures of the city—by burying them in their olive groves on the other side of the Porta Romana.

Looking at art is part of the atelier's curriculum, and with Charles Cecil's help, I make a plan of what to see while I'm here. It is said that one-third of the world's most important works of art are located in Florence. A lifetime isn't long enough—I have a week. Cecil's strategy is based on opening hours: museums in the morning, churches in the afternoon.

First encounters with famous pictures can be awkward. Face to face with Leonardo da Vinci's Annunciation, Uccello's Battle of San Romano I, Botticelli's magical Primavera, I feel an elation tempered by the shock of the familiar, as if reproduction has sucked the life from some images, disconnected their power to astonish. In the flesh, so to speak, Botticelli's women still look to me like English girls of the hippie era, when the poster was king.

Tour groups, ruthless as piranha shoals, boil around the great canvases. While the stars are under siege, I discover lesser-known paintings and enjoy the views from the gallery windows. There's a corner of the Uffizi from which you can look down on one side to the Piazza della Signoria, where the Neptune fountain and the colossal statues of David and Hercules are lined up under the façade of the Palazzo Vecchio, and on the other follow the sludge-green Arno, spanned by five of its bridges, to a vanishing point on the plains of Tuscany.

The intimate scale of Florence makes it easy, if hazardous, to get around on foot. Plagued by noise and traffic, this is a modern working city that stubbornly resists becoming a shrine to the past. Yet the ghosts of the Renaissance shine on. On every street I recognize faces from paintings in the museums. A brush with a scooter at an intersection reveals a proud beauty by Raphael... the Madonna of the Vespa. I glimpse an old man tending a tower of canary cages inside a doorway and recall Ghirlandaio's tender portrait of an old man and his grandson. Even the huge mastiffs that drag their fashionable owners past the dazzling storefronts on Via Tornabuoni could have bounded from a hunting scene by Uccello or Vasari.

Thursday is lecture night at the atelier. Cecil's scholarly talk on Masaccio, the first apostle of humanistic realism, attracts a wide audience from Florence's English-speaking community. Afterward, we stand around drinking wine from paper cups and talking earnestly about tradition versus Modernism. My uneasy defense of contemporary art is swept aside by Cecil's magisterial vision of a chain of ateliers extending back to Titian, Velázquez, Van Dyck—and forward to a new renaissance. The discussion continues over roast duck at a restaurant in the Oltrarno, where more- adventurous visitors have always come looking for the "real" Florence.

Next day, after class, I visit Santa Maria del Carmine's Brancacci Chapel and see for myself Masaccio's groundbreaking use of light and shade in the folds of a beggar's cloak. At San Marco, which was my grandmother's favorite church, I detect pencil-work behind Fra Angelico's pious frescoes—the drawing under the skin. My apprenticeship is opening my eyes, learning about line and form is helping me to unlock the secrets of the early masters.

I get "fresco neck" from constantly looking up. In the black and white marbled baptistery, where the visual miracle of Florence began, I notice a pew full of French nuns comfortably studying the ceiling mosaics in vanity mirrors, which gleam from their laps like gold plates.

Back in the studio, Ann makes regular rounds of the students' easels. I overhear phrases: "building up the values" and "getting the contouring right," and "might need to re-plumb... this leg, that arm... don't shade in too quickly."

There are 14 of us in the life class, 35 in the whole school (the atelier method discourages big numbers). Some are here short-term, to do a year's foundation course for art college or university; others, like Danielle DeVine, a willowy Bostonian, and the wonderfully named Ardis de Fries, from Portland, Oregon, are committed to becoming painters. The training is rigorous and intensive, and, looking around at the easels during break, I can only envy the promise on display.

"We always get a few who don't work out," a teacher explains tactfully. "You can tell by their attitude more than anything. They miss classes or they're not driven, they lack that passionate fury in their eye when they draw."

The moment I enter the studio and get settled at my easel, I become instantly and wholly absorbed. Time stands still, the universe contracts—I even forget a nagging toothache. Fred Hohler, a high-flying executive who attended Cecil Studios' summer school a few years ago, told me that the experience of learning to draw changed his life. I can see what he meant now. I think I may have got the "passionate fury" in my eye.

On Cecil's designated two days for teaching, the master stalks the studio floor using his charisma to breathe fire into our amateur souls. By the time he gets to me, I am eager to hear a critique, which, if you buy his continuity theory, carries an authority invested in him by, well, Michelangelo. He stands back, strokes his jaw (another Charlton Heston moment), and frowns alarmingly at my drawing.

"Lots of good things happening here. Contour is good...that is a likeness. Ideally you would have had more demarcation between light and shadow, then put your sfumato—the smoky transition from light to shadow—on afterward. You have a very fine outline. If you'd had another week, there's no telling what you would have done."

His enthusiasm is contagious, but I am under no illusions. I joined the atelier to learn an endangered craft, much as if I'd apprenticed myself to an artisan turning out faux antiques in an Oltrarno workshop. But I can't say that I haven't been affected by the experience. My days at the studio have taught me to look more intently not just at paintings but also at the world around me, and I want to go on doing this.

The myth of the first drawing, recounted in Pliny the Elder's Natural History, tells of a Greek maiden who watches her lover asleep by the fire and longs to preserve his beauty. Taking a charred stick from the embers, she traces his shadow, thrown onto the wall by firelight, and so makes permanent his presence in the world. The result may not have achieved all she hoped it would, but in her instinctive urge to make a mark, to record and so stay the fleeing moment, there lay an antidote to the human condition.

On my last evening, up at the Villa Fioravanti, I try to explain to the owner in halting Italian that during World War II my grandparents' tesoro was buried in her garden. When language fails me, I use my new skills to sketch a coffer and an open trench under an olive tree, which causes a bewildered Signorina Fioravanti (distantly related to Charlie and Gladys's friends) to comment brightly, "Ahhh... il coccodrillo!" Disappointing, perhaps. But then she asks if I would like to see the crocodile, which I've heard was given an elaborate funeral in the garden many years ago. She takes me upstairs to a room with panoramic views of Florence, and there on the wall above the TV, stuffed and glaring, hangs the once formidable guardian of our family silver.

Alitalia, Delta, and Continental fly to Florence from New York or Newark via Rome or Milan.

Charles H. Cecil Studios

Amateurs can sign up for the July session (from $2,541); serious students have to enroll for at least a year ($10,692) and must submit artwork to be considered for one of 12 spots. 68 Borgo San Frediano; 39-055/ 285-102; www.cecilstudios.org. Florence Academy of Art The school runs an all-year drawing program and, in July, month-long courses taught in English, including Anatomy and the Figure: Drawing in the Renaissance Tradition. 21R Via delle Casine; 39-055/245-444; www.florenceacademyofart.com. Cartoleria San Frediano A fantastic art-supply store that carries thick drawing paper, paintbrushes, and oils. 5R Via San Onofrio; 39-055/295-040.

Gallery Hotel Art

Just steps from the Ponte Vecchio, this sleek spot is part of the Ferragamo family's group of fashionable Florence hotels. (Its sister property, the Continentale, is across the street.) True to the hotel's name, art takes center stage: the reception area doubles as a gallery, showcasing works by contemporary photographers and painters. 5 Vicolo dell'Oro; 39-055/27263; www.lungarnohotels.com; doubles from $414.

Hotel Savoy

Grand and glamorous, the Savoy was given a refined $17 million overhaul by international tastemaker Olga Polizzi. Even if you're not planning to spend the night here, a visit to Florence isn't complete without an après-shopping cocktail on the square. 7 Piazza della Repubblica; 800/223-6800 or 39-055/27351; www.hotelsavoy.it; doubles from $556.

J. K. Place

This small, welcoming property quickly established itself as a home away from home for chic travelers who like to chat up their fellow guests around the communal breakfast table. 7 Piazza Santa Maria Novella; 800/525-4800 or 39-055/264-5181; www.jkplace.com; doubles from $343.

Garga

Behind the hole-in-the-wall façade, small linked dining rooms hum with fun and glamour. Service is deft and friendly, displaying justified confidence in dishes such as asparagus risotto and scaloppine di vitella al limone (veal scallops with lemon). 33/R Via San Zanobi; 39-055/475-286; dinner for two $105.

Simon Boccanegra

With its perfectly mottled stone walls, mismatched wooden tables, and adventurous Tuscan menu, it's no wonder this tiny trattoria across from the Teatro Verdi is always packed. 124R Via Ghibellina; 39-055/200-1098; dinner for two $85.

Trattoria Armando

Family-run, rustic but elegant, this half-century-old establishment serves some of the best Tuscan food in Florence. The chef's forte is making standbys like ribollita (cabbage-and-bean soup) and trippa alla fiorentina con fagioli (tripe with cannellini beans) taste delicious. Try the homemade pappardelle with wild-boar sauce. 140R Via Borgognissanti; 39-055/ 216-219; dinner for two $82.

A Room with a View

By E. M. Forster

A brilliant, gentle satire of the Edwardian art tourists who made Florence their own and put it back on the map after a long period of decline.

The Stones of Florence

By Mary McCarthy

This classic history of the art, architecture, and culture of the city paints a sharp portrait of the Medicis. Written in 1959, it contains amusing and telling meditations on then contemporary Florence.

Lavender Hill Studios

Co-run by a Charles H. Cecil Studios alum, Lavender Hill offers an informal sketch club and atelier sessions for amateurs as well as more advanced drawing and painting classes. Unit 101, Battersea Business Centre, 99109 Lavender Hill, London; 44-20/7801-3444; www.lavenderhillstudios.com.

Sarum Studio

Nicholas Beer, a former Charles Cecil pupil and instructor, teaches two-week classes in the sight-size method.

43 Park St., Salisbury, Wiltshire; 44-779/313-9563; www.sarumstudio.com.