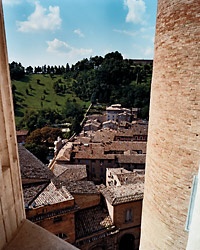

Simon Watson A view of Urbino's tiled rooftops, from the <em>studiolo</em> in the Palazzo Ducale.

Far from Capri's crush and Tuscany's throngs lie the untrammeled Adriatic beaches and pristine hill towns of Le Marche. Gini Alhadeff takes in venerable renaissance treasures—and some really superb fritto.

Simon Watson A view of Urbino's tiled rooftops, from the <em>studiolo</em> in the Palazzo Ducale.

Far from Capri's crush and Tuscany's throngs lie the untrammeled Adriatic beaches and pristine hill towns of Le Marche. Gini Alhadeff takes in venerable renaissance treasures—and some really superb fritto.

The artist Enzo Cucchi, one of Italy's finest, and a native of Le Marche, has a craggy profile that competes with the craggy cliff of Conero, where he told us to meet him at the Hotel Emilia, or rather, hotel emilia, as it modestly bills itself. Not modesty but frill-lessness, one soon discovers, is what the hotel offers, and when we got there and saw its unadorned white masses, which look like someone's demurely grand villa set into a green plain overlooking a dizzying drop to the sea, I instantly knew my story on Le Marche was on solid ground from the I-don't-care-if-I-never-go-anywhere-else point of view. The spare interiors, punctuated by Achille Castiglioni lights, and the 1970's structures that look like they might have been built by a cousin or disciple of Le Corbusier (but were in fact designed by Paola Salmoni, an architect from Ancona) go well with the hotel's guests, who come in various nationalities but share one distinguishing trait: they all speak in low voices. And they are all quite thin—though the food at the Emilia is fabulous, by the pool as in the dining room. You can eat your spaghetti with cozze (mussels) while absentmindedly following the movements of a young lissome couple playing Ping-Pong in white bathing suits or a sunbather wearing a triangular black tulle pareo embroidered with tiny mirrors over her thong bikini when not reclining on a chaise covered by the hotel's signature lilac towel. Cucchi likes to walk down to the beach of Portonovo below (no doubt in his biscuit-colored moccasins) and take a cab back up, since it's quite a climb. The Emilia provides a shuttle to and from the beach, which has white and black pebbles and is, according to Cucchi, the most beautiful on the entire Adriatic coast.

At six that day, I followed Cucchi's speeding BMW down the winding narrow road to the straight coastline of Senigallia. We parked and went to sit on the terrace of a café called Mascalzone, "the Lout." There I had an orange-colored Crodino, a bittersweet nonalcoholic drink of mysterious composition, and Cucchi had a glass of Verdicchio, a dry white wine that was one of the first to be exported to America. The drinks and green olives were brought to us by a sultry pirate in a black stretch hair band, low-slung black harem pants, and a black tank top, with pink bra straps peeping through. The terrace faces the street, but I sat with my back to it so I could see the beach and a volleyball court with an ongoing game. Everyone played in bathing suits; the women reminded me of the mosaics at the ancient Roman Villa Casale in Sicily's Piazza Armerina, which show women playing ball in bandeau tops and briefs—an early version of the bikini. The popes may have stuck their golden staffs and built their churches and monasteries all over the hills, but here the way of indulgence has won over that of penance.

A schizophrenic existence is possible in Le Marche, as one shuttles back and forth between the austere hill towns and the sybaritic resorts and bathing establishments along the Adriatic, where for four to five months of the year raked sands are ornamented by a forest of striped, polka-dotted, and bright-colored umbrellas, and neat rows of deck chairs and sun beds present a world dedicated to rest and recreation, set within a "real" one of small cities, traffic, shops, and bustling life. People come from all over Europe to places like Senigallia, whose medieval center not all visitors notice and where a few hundred cafés and bagni are packed from late morning until sunset.

Le Marche is a lesser known part of Italy, with a 111-mile-long coastline—a protruding left hip on the Adriatic Sea—and stretches of unspoiled countryside extending into Umbria. The hills are the real monument here, and the way to see them is by accumulating hours driving through them or observing them from a window in a house on top of such a hill, like the one where my friends Remo Guidieri and Danielle Van de Velde live and write when they are not in Paris, in a town called Moresco. From most of the windows of their house, you can see snow-capped mountains on one side and the Adriatic Sea on the other. In between are the hills.

Le Marche was so named in 1105 when three marches, or border regions, between papal and imperial lands were joined by the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV. One can go practically anywhere in Le Marche, taking the highway along the coast when necessary for speed, and be back by nightfall. Every evening of my stay with the Guidieris, after scouring the countryside, I would return to the long refectory table in their dining room and sit on the wooden bench next to Remo or Danielle to plot the following day's itinerary.

Moresco, a fortress with some 400 inhabitants, about 40 miles south of Conero, is the same small town the Guidieris came to about 20 years ago, when Le Marche was the not-Tuscany, not-Umbria of Italy if you'd arrived too late in either of those regions to buy or rent anything. A heptagonal Moorish tower dominates a triangular settlement built mostly of stone. On a Sunday morning, the streets and square look as they must have centuries ago: deserted and quiet till the doors of the church open and the parishioners all spill out, chattering among themselves.

One Sunday Remo came as my guide, and a few hours expanded to what seemed like days as we drove around the more hidden Marche that he seemed to know intimately. Like the hills that can only be "seen" in increments, through a progression of miles and hours, Le Marche's treasures are scattered all over the region—a few, sometimes one, to every hill town.

Near Montecosaro, the bare-brick Romanesque church of Santa Maria a Pié di Chienti, flanked by a smoke-filled café teeming with men playing cards, has veined alabaster windows that look like abstract stained-glass designs and bathe the interior in pale golden light. En route to Fiastra, we passed the Marchigiano designer Diego della Valle's immense new shoe factory. Shoes constitute the chief industry of Le Marche, aside from tourism.

At the abbey of Fiastra it occurred to me that cloisters might have been the draw, or at least the consolation, of a monastic life. Fiastra is one of the most serene, with a shaded portico and an ample courtyard that has a well at the center. The windows of the monks' cells line the story above the arches. Fiastra is surrounded by a large park and a nature preserve of some 4,000 acres; in their private yard by the abbey the monks could be glimpsed tending to the plants and trees.

We went to Monte San Giusto to see Lorenzo Lotto's Crucifixion, the altarpiece in a tiny church, Santa Maria in Telusiano. At the top are depicted three crucifixes, Christ and the two thieves; then soldiers on horseback, holding lances poised at all angles; and below, Mary, wrapped in a dark blue veil, collapsing to the ground at the dark heart of the painting, her arms flung out, a man holding her up on one side, a woman on the other, as though she, too, were being crucified. The thieves, their white loincloths flapping in the wind, seem about to fly off their crosses.

In Fermo, we stopped briefly to see the late archbishop, Don Gennaro, who had grown up in the north, by Lake Iseo, and was the neighbor of an old friend of mine. I made a faux pas by inquiring whether Loreto came under his jurisdiction. It doesn't; as one of Italy's most important sanctuaries, along with Assisi, it has its own see. Pilgrims flock from all parts of the world to worship the Madonna of Loreto, who appears black because the original statue was made of dark wood. She is wrapped tightly in a brocade cone decorated by horizontal crescents, with the baby Jesus swaddled so that his smaller head protrudes next to hers. She looks a bit as if she had materialized from another planet, and her house is reminiscent of a Hindu temple—dark, the bricks blackened by time and candles, and packed with so many faithful you can barely find a place to stand. Legend has it that the Madonna's humble dwelling in Nazareth flew itself, or was carried by angels, all the way to Loreto from the Holy Land. Actually, according to more recent findings, it was built next to a cave, then moved to Italy by ship at the time of the Crusades. The Holy House, one of the most beloved Catholic shrines, was encased in sculpted marble panels by the architect Donato Bramante, as it seems the original construction was thought too "rural." Those are, in turn, contained in a basilica, so it is a shrine within a shrine within a shrine.

The Madonna of Loreto and Saint Joseph of Copertino, whose sanctuary is in Campo Cavallo near Osimo, about 12 miles to the north, are both said to protect fliers, or aeronauts, as they used to be called. Apparently Saint Joseph could float off the ground; the current monks at the saint's former convent say he "took God so seriously he could literally fly." Flying is an appealing prospect from the cliff of Conero or from the walled ramparts of Recanati.

Recanati is a pilgrimage site for writers. Its glory is the 19th-century poet Giacomo Leopardi, who railed against his native town and the straitlaced atmosphere of Le Marche. His only distractions were the extraordinary library (which can be visited) assembled by his father, Count Monaldo, the sweeping views, and a hill he immortalized in "The Infinite," Italy's most celebrated sonnet. Now one ventures out to see Lorenzo Lotto's Annunciation at the small Colloredo-Mels museum in the historical center of town. It is a thrilling interpretation of the event: a muscular, wild-eyed, blue-winged angel lands bearing a tall white lily, a tabby cat leaps out of the way, arching its spine, and the Virgin Mary—a brunette for a change and apparently no older than 16—throws up her hands and ducks, as though the angel had landed with a crash, taking her by surprise. Lotto, who was born in Venice around 1480 and lived in Le Marche early in his career, moved back there toward the end of his life, becoming a lay brother at the monastery of the Holy House in Loreto. He was poor and, by most accounts, racked by religious doubt. As for Leopardi, he fled from his chilly parents and his father's library, where in seven years he had taught himself everything from the classics to astronomy, and died of typhoid in Naples, possibly after eating a gelato. Gelati are no longer lethal, and an attack of melancholy in Le Marche can be cured by a two-hour drive to Rome, or a 10-minute one to the sea.

Even in the fall and winter, except perhaps over the Christmas holidays, one can go to a wonderful fish restaurant like Uliassi in Senigallia, run by the chef Mauro Uliassi and his sister, Catia, and on a sunny day have lunch on the terrace and look out onto the sandy beach and a limitless expanse of gray-green Adriatic. There we tasted a fritto—assorted fried fish and vegetables—that had the best aspects of tempura and Italian frying combined: tiny tender octopus, sticks of zucchini and eggplant, a zucchini flower splayed out in a fan shape on the wooden tray it all came on. The delicious squid-ink strigoli—a tubular pasta—came with clams, octopus, and cherry tomatoes.

The previous evening, Enzo Cucchi had arranged for us all to have dinner at La Madonnina del Pescatore, in Senigallia's Marzocca area. There is a statue of the Madonna that fishermen pray to before setting out to sea—hence the name of the restaurant. That's where the quaintness stops, since the place, which opened in 1984, is a minimalist concrete box with a glass façade. The waitresses dress in beige. As soon as we sat down, they brought us Parmesan sorbet in crisp cylindrical wafers. We had eight light-handed courses in all, including raw shrimp marinated in orange sections, fried whitebait (bianchetti) as small as paper clips, and a Senigalliese brodetto, or fish soup. It was a kind of culinary magic show.

To reach Le Marche from anywhere else in Italy, sooner or later one must scale the Apennines, so it is with eyes washed in snow and dazzled by peaks that one comes to the rolling hills of Le Marche, especially in winter.

Even Urbino, the masterpiece of Renaissance architecture described by Baldassare Castiglione in the opening lines of The Book of the Courtier as a city in the form of a palace, would be hard to imagine without the surrounding landscape, which is visible from every balcony and window of the Palazzo Ducale.

Like other Italian "capitals," Urbino is a small town that someone, in this case the Duke of Montefeltro, suddenly envisioned as the center of the universe. The duke, judging from Piero della Francesca's portrait of him, must have had an appetite for the truth, for it is not a flattering picture—his beaklike nose appears broken at the bridge, and he has a wart beneath one ear, dark circles around his hooded turtle eyes, thin lips. But the red hat the duke decided to put on does ennoble the whole and is as brilliant a solution as any he made in the course of transforming Urbino into a Renaissance hub. He was the Lorenzo il Magnifico of this part of Italy. An admirer of Macchiavelli, he arranged to have his half-brother killed in a court intrigue, after which the people of Urbino called on him to be their ruler. We may have his guilty conscience to thank for one of the most wondrous commissions inside the exquisitely unusual ducal palace Francesco di Giorgio Martini designed for him: the very moving Cappellina del Perdono, or Chapel of Forgiveness.

His study, the Studiolo del Duca, is a cubicle completely paneled with intricately inlaid wood depicting arches through which you see unlimited landscapes—one shows a squirrel devouring a nut, another a cupboard stacked with books in haphazard piles. In that inspiring cell he may have thought up his plan to invite Piero della Francesca to Urbino to paint his Flagellation of Christ and portraits of his wife and of himself. (At his court lived another painter whose son, Raffaello Sanzio, became known to the world as Raphael, and whose house is only a few blocks away.) One can also visit the immense vaulted spaces of the stables, the kitchens, and the duke's bathing chamber in the basement.

I asked Remo's friend Nello, the pharmacist of Moresco, who still mixes his own remedies and collects Byzantine icons, to characterize the cooking of Le Marche, and he said, "Not chiles." So if not chiles, I pressed him, then what?"Cloves," he replied. A recipe for the most typical local dish, a lasagna called vincisgrassi, invented in 1799 in honor of Prince Windischgrätz, an Austrian general stationed in Le Marche, also includes cinnamon and nutmeg in a sauce of sweetbreads, calf's brains, prosciutto, porcini mushrooms, and, naturally, béchamel. Driving from Moresco to Ascoli Piceno, home of the Venetian Renaissance painter Carlo Crivelli (and of the stuffed and fried green olives called ascolane, which you eat with creme, dollops of sweet fried custard), the rhythm of the rippled landscape becomes hypnotic. The first glimpse of Ascoli is of its many bell towers (there were once 200), a surreal gathering one can imagine holding a rarefied philosophical discussion when no one is watching. In the restored Art Nouveau Caffé Meletti, we had a tuna-and-artichoke sandwich on white bread, which seems to be a staple at most cafés in Le Marche.

Between hill towns, we visited Pesaro, a genteel turn-of-the-19th-century beach resort with tree-lined avenues and freestanding Art Nouveau villas, and ate at Il Cortegiano, a restaurant set in a neo-Gothic palazzo, where we were given a table with a view of a shaded garden and a wall inset with majolica. This town's reigning spirit is Gioacchino Rossini, who is celebrated every August in a festival exclusively dedicated to the performance of his operas.

On our arrival in Le Marche, we had driven up the highest hill overlooking the Adriatic, to the medieval Cathedral of San Ciriaco. In it, aside from the saint's relics, was a painting of the Virgin said to protect travelers from storms at sea. Then we headed toward Iesi, the hometown of the composer Pergolesi. It started to rain. We wanted to stop for lunch but could barely see the road, and then, on an incline, the engine flooded and we stalled. Suddenly a car appeared, overtook us, then stopped. Using a nylon rope he happened to have with him, the driver hitched us to his car, then hauled us up the hill till our engine started again. We asked for directions to a restaurant, and he said we should follow him, since he was on his way to lunch. He led us through the deluge to the middle of a flat plain and a trattoria that looked nothing like a restaurant: it was hidden, like most treasures of Le Marche, for all to see.

You need to be a good driver in Le Marche; the roads are narrow and often steep. Fly to Ancona and rent a car. For speed, take the A14, connecting the entire region along its 111-mile coastline, from Pesaro in the north to Ascoli Piceno in the south. For pleasure, drive the strade statali through Le Marche's beautiful landscapes.

Most hotels are along the coast or in the Conero area, near Ancona. For a feel of hill-town life, rent a house. Le Marche Explorer Rental Properties represents an extraordinary selection of restored farmhouses, convents, and apartments at rates from $885 a week. Or try a room or suite in an agriturismo villa or bed-and-breakfast like Palazzo dalla Casapiccola.

Hotel Fortino Napoleonico

A converted fortress, with a swimming pool, a garden, and endless curving

beaches in front and on either side. 166 Via Poggio, Portonovo; 39-071/801-450; www.hotelfortino.it; doubles from $375 a night, seven-night minimum stay.

Hotel Emilia

Poggio di Portonovo, Ancona; 39-071/801-145; www.hotelemilia.com; doubles from $275.

Albergo San Domenico

Set in a 14th-century monastery and 16th-century convent, facing the ducal

palace. 3 Piazzale Rinascimento, Urbino; 39-072/22626; www.viphotels.com; doubles from $138.

Palazzo dalla Casapiccola

Ten suites in a 1600's mansion in the historic center of Recanati, with a

beautifully maintained garden. 2 Piazzola Vicenzo Gioberti; 39-071/757-4818; www.palazzodallacasapiccola.it; suites from $65.

As in the rest of Italy, lunch or dinner in Le Marche is a perfect pretext for a drive.

Da Andreina

Charcoal-grilled game in a brick house on the outskirts of Loreto. 14 Via Buffolareccia;

39-072/164-934; dinner for two $100.

Il Castiglione

Baked branzino in the elegant dining hall of a 1900's villa. 148 Viale Trento, Pesaro;

39-054/164-934; dinner for two $60.

La Madonnina del Pescatore

11 Lungomare Italia, Marzocca di Senigallia; 39-071/698-267; dinner for two

$125.

Migliori

A food shop for ascolane (stuffed olives) and creme (dollops of custard), ready to be fried

and eaten (together). 2 Piazza Arringo, Piceno; 39-0736/250-042.

Ristorante Farfense

Potato dumplings in meat sauce, served in a brick-vaulted dining room in a former

monastery, with views of the sea 25 miles away. 41 Corso Matteoti, Santa Vittoria a Matenano (near Ascoli Piceno);

39-0734/780-171; dinner for two $75.

Il Saraghino

On the beach at Numana, mixed fried fish and vegetables and tagliatelle with squid ink.

209 Via Litoranea, Lungomare di Levante, Numana, Marcelli; 39-071/739-1596; lunch for two $100.

Susci Bar Clandestino

Young chef Moreno Cedroni, who has developed an Italian version of sushi (he

spells it susci), and his wife represent the new face of Le Marche cuisine. Baia di Portonovo; 39-071/ 801-422; dinner for

two $190.

Uliassi

6 Banchina di Levante, Senigallia; 39-071/65463; www.uliassi.it; dinner for two $250.

Caffé Meletti

Aperitifs and antipasti in an authentic Art Nouveau setting. Piazza del Popolo,

Ascoli Piceno; 39-054/191-6145.

Galleria Nazionale delle Marche

Paintings by Paolo Uccello and Piero della Francesca. Palazzo Ducale,

3 Piazza Duca Federico, Urbino; 39-072/22760.

Raphael's Birth House

The artist was born and taught to paint by his father here, though none of his

paintings are on display. 57 Via Raffaello, Urbino; 39-072/232-0105; www.accademiaraffaello.it.

Rossini Opera Festival

Performances of works by the native-son composer, every August in Pesaro.

39-072/1380-0294; www.rossinioperafestival.it.

Pinacoteca e Museo delle Ceramiche

Ceramics from the 1500's to the present, including 1900's

majolicas of Pesaro's Ferruccio Mengaroni. 29 Piazza Toschi Mosca, Pesaro; 39-072/138-7541; www.museicivicipesaro.it.

Villa Imperiale

A fortress plus a Renaissance villa, built in four levels on a hillside, with

geometric gardens. 63 Strada San Bartolo, Pesaro; 39-072/169-341.

Santa Casa and Basilica

The Holy House of the Black Madonna. The surrounding area is full of shops

selling fascinating souvenirs. Palazzo Apostolico, Piazza della Madonna, Loreto; 39-071/970-104.

Museo Villa Colloredo Mels

Recanati; 39-071/757-0410.

Santa Maria a Pié di Chienti

Montecosaro, Macerata; 39-073/386-5241.

Church of Santa Maria in Telusiano

Monte San Giusto, Macerata; XII Via Gregorio.

Abbadia di Chiaravalle Fiastra

Via Abbadia di Fiastra; 39-0733/202-942; www.abbadiafiastra.net.

La Basilica di San Nicola a Tolentino

Another glorious cloister, from the 14th century. Tolentino,

Macerata; 39-0733/976-311.

Other Towns Worth Seeing San Leo, Fano, Senigallia, Fermo, Osimo, Camerino, Iesi, Fabriano, Cupramontana, Torre di Palma, and San Severino Marche.

Leopardi: Selected Poems

Translated by Eamon Grennan. Work by Le Marche's most famous author.

Cucina of Le Marche

By Fabio Trabocchi (Ecco, October). A cookbook-memoir tribute to the

region's culinary bounty.