Gamma Liason

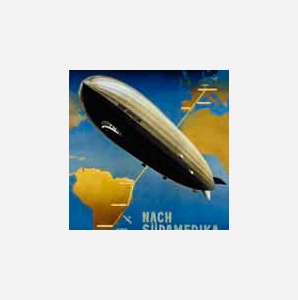

A hundred years after the first zeppelin flight, a new generation of passenger airships is taking to the skies

Gamma Liason

A hundred years after the first zeppelin flight, a new generation of passenger airships is taking to the skies

Engines buzzing, the great craft tilts upward and begins to rise. As the ground falls away, the verdant slopes and rocky outcroppings resolve into the craggy splendor of the Swiss Alps. A moment later the ship levels off once more, gliding with stately purpose amid the fleecy clouds of the crisp bright day. The glissando of a Chopin étude wafts through the cabin, nearly muffling the faint drone of the engines. A white—jacketed steward brings a glass of champagne. Lulled by the gentle swaying of the hull, you drink too quickly, and find yourself overwhelmed by the giddy urge to stick your head out the window. So you do. Unfastening the latch, you slide back the pane, and there you are, the Alpine air whipping through your hair. As you gaze at flocks of tiny cattle a thousand feet below, you think: This is how flying ought to be.

Well, that's how it used to be. And, if all goes according to plan, that's how it will be again, soon.

Eighty years ago, dirigible airships seemed the likely future of travel. Compared to the rickety airplanes of the day, airships had enormous range and lifting power. White-linen dinner service aboard stately German zeppelins was the byword of futuristic luxury. The British and Americans also planned substantial dirigible fleets. The British R101, launched in the autumn of 1929, held sleeping berths for 100 passengers, a promenade deck, and a smoking room.

Of course, the airship's heyday was short-lived. About a year after its launch, the R101 crashed during testing in France, killing 48 of the 54 people aboard. In 1932 the U.S. flying aircraft carrier Akron broke apart during a storm; three years later her sister ship, the Macon, met a similar fate. The death knell of airships was sounded in 1937 by the famous disaster at Lakehurst, New Jersey, when the 804-foot-long Hindenburg crashed and burned, killing 36.

With the coming of World War II, and the dawning of the jet age thereafter, the era of grand passenger airships became a historical footnote. Were it not for Goodyear and its fleet of advertising blimps, the airship might have become entirely extinct.

But today, like some giant gaseous phoenix, the passenger airship is rising again. Most of the pioneering work is being done in Europe—on both rigid airships, or zeppelins, whose gas envelopes contain an internal skeleton, and blimps, which keep their shape from gas pressure alone. Airship Technologies, a U.K.—based blimp manufacturer, is now building a dirigible capable of carrying as many as 52 passengers. Dubbed the AT—04, the 269—foot—long airship is scheduled to make its first flight this fall and be certified for sightseeing excursions between London and Windsor Castle sometime in 2001.

And this July 2, exactly a century after Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin's first airship took to the sky, the German company that bears his name—Zeppelin Luftschifftechnik—will christen the 246-foot-long, 12-passenger LZ N07, the first rigid airship to fly since World War II. Thanks to the ship's carbon-fiber skeleton, the engines on the LZ N07 can be positioned away from the gondola, reducing noise. The engines will have an advanced tilt-rotor design, making the airship far more maneuverable than conventional designs and requiring fewer ground crew members. Zeppelin Luftschifftechnik expects to make passenger trips starting next year (itineraries haven't yet been determined).

Meanwhile, a Swiss company, Skyship Cruise, plans to take sightseers on hour-long zeppelin flights over the Alps sometime in 2001, with a tentative price of $250 per person.

On this side of the Atlantic we don't have to wait: in Las Vegas, the Lightship Group, which operates 16 advertising blimps around the world, is now offering nightly one-hour rides aboard the 165-foot-long Las Vegas Airship. Carrying nine passengers, the blimp cruises at 1,300 feet above the pulsating neon of the Strip. The Lightship Group's bread and butter remains the advertising dollar—in this case, from the promotional Web site Vegas.com, whose giant logo is emblazoned on the sides of the airship. Passenger fares are simply an afterthought.

The day's first sightseeing flight begins at dusk and departs from an unassuming dirt lot at the North Las Vegas Airport. As each passenger climbs aboard, crew members remove 25-pound bags of lead to compensate for the additional weight. As in all blimps, the engines attach directly to the gondola, so the noise is substantial, though not overwhelming—something like being in a laundromat full of washing machines on spin cycle. To dampen the noise, everyone wears a headset with microphone, which also lets them listen to a recorded tour offered in five languages.

When everyone's aboard, the pilot revs the engines, the ground personnel release the restraining ropes, and the glowing white orb buzzes off into the sky. Soon the ring of mountains around Vegas is glowing orange in a desert sunset. The tip of the 1,150—foot Stratosphere tower slips past, nearly level with the side window.

Alan Judd, a blimp pilot for 16 years, has an instinctive feel for the lumbering behemoth. He's able to match its speed to the wind outside so that the blimp hangs motionless over the ground. Unlike a plane, which bounces over pockets of turbulence, the airship eases through them as a ship rides swells. Indeed, the sensation is more nautical than aeronautical. "It's like sailing a big yacht," says Judd.

The cabin isn't exactly spacious—only 14 feet long, with a single aisle down the middle—but there's plenty of headroom, and passengers can walk around freely, without fear of being toppled by turbulence. There's even a small window that they can stick their heads out of. (Spitting is discouraged.)

The sunset flight is billed as a "Champagne cruise," but the little blimp, one—hundredth the size of the Hindenburg, doesn't offer the same quality of service as the old liner. There's no room for a steward, so each passenger is handed a paper bag with a half—bottle of sparkling wine and a plastic flute. But the experience is nonetheless intoxicating. After all, there are fewer than 30 airships worldwide, and the Las Vegas Airship is for now the only one selling tickets. For some passengers, the ride is a foretaste of what might be a new golden age for blimps. For others, it's a way of reviving a dream from long ago, when air travel meant more than a cramped and hurried dash between points A and B. "The other day, a lady came up to me and said, 'I'm seventy—eight years old, and I've wanted to do this since I was twelve,' " says Lightship mechanic Al Williams with a smile. "A lot of our customers are like that."

Lightship Group 877/582—5467 or 702/646—2888; one—hour flights start at $179 per person.

BUT HOW SAFE IS A BLIMP?Despite the example of the Hindenburg, the answer is: very safe. Modern airships float on helium instead of the explosive hydrogen that doomed the Hindenburg. They're considered one of the safest forms of aviation today. Goodyear, for example, hasn't had a single fatality in more than 50 years of operating its blimps.