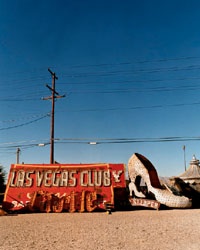

Trujillo/Paumier Retired marquees from Las Vegas, Nevada, resorts of an earlier era.

On a drive from Las Vegas (New Mexico) to Las Vegas (Nevada), James Crotty and Michael Lane discover faded Western glory, oddball characters, and a lost chapter of American history (in a Burger King)

Trujillo/Paumier Retired marquees from Las Vegas, Nevada, resorts of an earlier era.

On a drive from Las Vegas (New Mexico) to Las Vegas (Nevada), James Crotty and Michael Lane discover faded Western glory, oddball characters, and a lost chapter of American history (in a Burger King)

Las Vegas, New Mexico, isn't much of a town these days. Its tumbleweed look and feel make it seem more like an afterthought than a destination. In fact, after barreling along the eastern slopes of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains on the way down I-25, most travelers settle for a quick refuel, occasionally asking "Where are the casinos?" at local filling stations. If only they knew the town's history, such a question wouldn't be far off the mark.

From 1821 to the late 1870's, Las Vegas was a major stop on the Santa Fe Trail, bringing settlers west from Missouri (the Santa Fe Trail Interpretive Center, across from Rough Rider Antiques, tells the tale). But the pivotal moment in the town's history was the arrival of the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad on July 4, 1879. With it came legitimate businesses, as well as a fair amount of riffraff, including murderers, thieves, gamblers, swindlers, and gunmen. Chief among them were the wily Doc Holliday, Big Nose Kate,and noted desperado Billy the Kid. Indeed, the real Wild West started right here, 6,400 feet up in "the meadows" of New Mexico.

But these days, it's Las Vegas, Nevada, that gets all the ink. That got us thinking: Perhaps Vegas, Nevada, is the ersatz version of Vegas, New Mexico. Perhaps one is the reality, the other a tall tale writ large. What would a trek between these bookends of the Southwest tell us about each city, about the region, and even about America?

We'd always been interested in quests. In 1986 we left San Francisco and hit the road, publishing a public diary of our journey titled Monk, the Mobile Magazine from the dashboard of our 26-foot Fleetwood Bounder Monkmobile. We called ourselves monks because, like the Zen monks of Asia and the Christian peripatetics of Europe, we believed travel was transformative. Our quest at that time was to find the true spirit of each place we visited. This quest was similar: to travel from Vegas to Vegas in search of the real Southwest—except that we planned to complete this trip in four days, instead of 12 years.

Driving past the downtrodden outskirts of Las Vegas, New Mexico, we hit the town's dusty, historic core. Surrounded by bright blue sky and a gritty landscape exploding from rugged hills, we parked our aqua-green 1965 Chrysler Newport and walked past dirty pickups and scrubby pines. We felt like two outlaws in a spaghetti western. Like a lot of renovated towns, Las Vegas has a mismatch of landmarked buildings (more than 800 on the National Register of Historic Places) alongside drabpre-fab structures. The grande dame of the square is the three-story Plaza Hotel, which evokes the area's mining, gambling, and whoring boom. Pat Garrett and Voodoo Brown once stayed here, as did early cowboy-film star Tom Mix. Not much has changed since the glory days when the Plaza was the belle of the Southwest. The 36 rooms are still tall, quaint, and cozy. It feels like a good place to be trapped in a snowstorm.

A good hour west of Las Vegas on I-25 is Santa Fe, the epicenter of this region's philanthropic indulgence and, not coincidentally, the world capital of Native American schlock. Santa Fe, which bills itself as "the city different," is the nation's third-largest art-buying capital, even though it's really more about "arts and crafts." From the chintz and glitz of Canyon Road to the faux-Western shtick of the Cowgirl Hall of Fame restaurant, we decided that Santa Fe looked more like a theme park and less like the melting pot of the Southwest it pretends to be. So we found ourselves continuing on the Taos Highway in search of the real deal—except when most travelers to the Southwest go searching for the real deal, they mean humble potters working in quiet seclusion on one of the eight northern pueblos, or some rustic phantasm of Hispanic rural life conjured up after seeing The Milagro Beanfield War. But in northern New Mexico, Native American and Hispanic cultures are the mainstream. They form the basis of the area's huge tourism industry, including the annual Indian and Spanish markets, when thousands of locals make a handsome living off out-of-town collectors.

If you want real in these parts, you have to travel outside the Native American-Hispanic nexus. And once you do, it isn't long before you uncover a theme that unites all areas and peoples in the Southwest: the United States government. Not only are the feds the region's largest landowner and employer, but they've used the area as a vast nuclear playground, from the Trinity atomic site in Alamogordo, New Mexico, to the outskirts of Santa Fe, traversed by WIPP nuclear waste trucks. Nowhere is the federal presence more apparent than in the former "secret city" of Los Alamos, New Mexico. It was here, at the Los Alamos National Laboratory (better known as the Lab), that scientistscreated the world's first two atomic bombs.

We turned onto Highway 502 at the Cities of Gold Casino, our destination not the Lab, but rather an infamous repository of Lab detritus called the Black Hole, where Ed Grothus, a former Lab machinist, has spent the past several decades collecting experimental cast-offs and other non-radioactive junk. Approaching the Black Hole, we noticed a row of obsolete bombs lined up near the fence. Ed—or Atomic Ed, as folks around here call him—warily greeted us from his storefront as we examined water mines, bomb encasements, and large rectangular metal objects that looked similar to high-priced sculptures we'd seen earlier that day in Santa Fe.

Ed launched into a lengthy description of his collection, which soon segued into rants about government waste and cover-ups. But probing his wizened face, you might feel a little paranoid, too, knowing that he's been up close to what

J. Robert Oppenheimer called "the destroyer of worlds." Ed views the Black Hole as an unofficial museum of the nuclear age, a place where Lab artifacts are stored and often placed on sale. For $300 we could have driven away with a 1,000-pound bomb strapped to the roof of our Chrysler.

Leaving Los Alamos, we drove south on Highway 4 to San Ysidro, then north on 550 past Chaco Canyon, and up into northwestern New Mexico on Highway 64. At the junction of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah, we found the Four Corners, a pointless (except maybe to play Four Corners Twister) tourist stop saved only by its proximity to some of the country's most stunning landscapes. Heading north from Kayenta, Arizona, as we drove past towering golden-red rocks looming like earthen cathedrals we witnessed an explosive light show from rolling thunderheads. Pitch-black clouds dumped torrents of rain in the distance while an electric storm seemingly orchestrated by Thorsent bolts of lightning across the horizon and down to earth while the descending sun shone brightly across the desert floor, flooding the valley with a near-blinding luminescence.

Just beyond Monument Pass, as we entered Utah, we made a right turn on the road adjacent to Monument Valley Park. Photographers have come here since the days of Ansel Adams, but the marketer who saw the early commercial potential of the valley was Harry Goulding, who persuaded director John Ford to shoot his Hollywood westerns in the area. Across the valley, going west down the same road that took us to the trading post, we spent the night at Goulding's Lodge, where the front desk carries all the movies that Ford filmed here, such as Stagecoach and The Searchers. One can see the real thing by day and watch the Hollywood version at night.

From Monument Valley, we headed south on Highway 163 and returned to Kayenta, making a quick stop at Burger King, which is a very odd place to encounter Navajo history. But inside is an exhibit on Navajo code talkers, the subject of the 2002 John Woo film Windtalkers. Most of the artifacts come from King Mike, a code talker and Marine private first class in the Pacific theater of World War II. The exhibit was put together by Richard Mike, King Mike's son and owner of the Burger King. It chronicles the vital role the code talkers played in rendering Allied code indecipherable to Japanese intelligence, thus helping to win the war in the Pacific. The day we were there, a Navajo family of four was dining on Whoppers, fries, and milk shakes;next to them was a posse of Japanese tourists enjoying the same. Old enemies, brought together over an icon of the New West, the fast-food hamburger.

The next day, we followed local roads west, crossing the border into Utah before picking up I-15 and zooming down to Las Vegas, Nevada. There we saw some of the great themes of the Southwest—fierce libertarianism, epic grandeur, unabashed mythmaking—manifested in dazzling multicolor palettes, as if the collective id of the American frontier were being spilled forth wholesale onto the desert tarmac.

Indeed, if Vegas, New Mexico, is the understated, genuine Wild West, then Vegas, Nevada, is a fabrication made attractive to the masses. To see how Las Vegas played on this theme, we headed to the old downtown casinos along Glitter Gulch. The city's signature neon creation, a cowboy named Vegas Vic, greets visitors from atop the old Pioneer Club, and the Wild West lives on at Binion's Horseshoe and at Sam's Town, a casino known for its wilderness and mining-town façade. But according to local Anthony Bondi, who grew up in Las Vegas during the heyday of the Rat Pack and whose father was a marker at the casinos before electronic boards killed his job, it was the gamblers from back East who wanted to see Vegas as the Wild West. After all, Easterners had been reinventing themselves out West since Brooklyn-born William H. Bonney (a.k.a. Billy the Kid) hit the region just after the Civil War. The casino operators simply played on that deep-seated mythopoetic longing. They continue to do so to this very day. Not with Wild West icons, but with the flip side of the Western imagination—the larger-than-life, the improbable, the genuinely fantastic. Bob Stupak's Stratosphere Tower is a testament to the city's propensity for tall tales. So, too, is the ornate Venetian, which, with its Sistine-like frescoes, earnestly tries to complete the circle back to the settlers' myth of their own refined European roots.

The Southwest is a land of opposites: unmatched beauty is mixed with unparalleled destruction, worship of the land with worship of technology, unbridled greed with profound spirituality, humility with hubris. Throughout our journey we found hints of the region's fiercely independent eccentrics, but we also found those who authentically engage native ways. From their bold fusions—earth-centered yet cutting-edge, entrepreneurial yet egalitarian—a new, and often deeply true, Wild West is being born.

JAMES CROTTY and MICHAEL LANE are the authors of Mad Monks on the Road, The Mad Monks' Guide to New York City, and The Mad Monks' Guide to California.

Day 1: 67 miles Take I-25 from Las Vegas, New Mexico, to Santa Fe.

Day 2: 405 miles Drive north from Santa Fe on 285, taking 502 west to Los Alamos. Get on 4 south, passing through Jemez Springs and San Ysidro; turn north on 550, then take 64 west and enter Arizona. Drive north on 160 to Four Corners, returning south to Kayenta. From Kayenta, head north on 163 to Monument Valley.

Day 3: 292 miles Drive 163 south back to Kayenta. Take 160 west to 98. Follow it north past Page, Arizona, and the Glen Canyon Dam, taking 98 into Utah (it becomes 89). Take 89 to I-15 shortly after Hurricane, Utah; drive south to St. George.

Day 4: 118 miles Hop on I-15 south out of Utah, heading straight for Las Vegas, Nevada. Cruise the Strip—both the newer version and its Rat Pack ancestor.

The FactsWHERE TO STAY

The Plaza Hotel DOUBLES FROM $96. 230 PLAZA, LAS VEGAS, N. MEX.; 800/328-1882 OR 505/425-3591; www.plazahotel-nm.com

Inn of the Anasazi DOUBLES FROM $199. 113 WASHINGTON AVE., SANTA FE; 800/688-8100 OR 505/988-3030; www.innoftheanasazi.com

Goulding's Lodge DOUBLES FROM $68. MONUMENT VALLEY, UTAH; 435/727-3231; www.gouldings.com

BEST VALUE Sam's Town Hotel & Gambling Hall DOUBLES FROM $50. 5111 BOULDER HWY., LAS VEGAS, NEV.; 800/634-6371 OR 702/456-7777; www.samstownlv.com

PLACES TO SEE

Black Hole 4015 ARKANSAS ST., LOS ALAMOS, N. MEX.; 505/662-5053

Four Corners RTE. 160 AT THE JUNCTURE OF ARIZONA, UTAH, COLORADO AND NEW MEXICO

Navajo Code Talkers Exhibit BURGER KING, KAYENTA, ARIZ. OPEN DAILY 6 a.m.-10:30 p.m.

Vegas Vic FREMONT AND FIRST STS., LAS VEGAS, NEV.

Binion's Horseshoe Hotel & Casino 128 E. FREMONT ST., LAS VEGAS, NEV.; 800/622-6468 OR 702/382/1600; www.binions.com

Stratosphere Tower 2000 S. LAS VEGAS BLVD., LAS VEGAS, NEV.; 800/998-6937; www.stratospherehotel.com