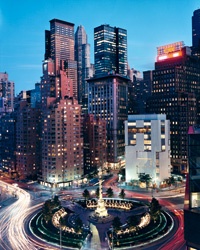

© Thomas Loof Manhattan’s New Museum of Modern Design

With the move to a boldly--and controversially--reimagined building in the heart of Manhattan, the Museum of Arts and Design arrives on the scene with a new name and an expanding cultural vision.

© Thomas Loof Manhattan’s New Museum of Modern Design

With the move to a boldly--and controversially--reimagined building in the heart of Manhattan, the Museum of Arts and Design arrives on the scene with a new name and an expanding cultural vision.

Occupying a trapezoidal island diagonally across from Central Park, the 12-story, white-marble building by Edward Durrell Stone stood for close to half a century at 2 Columbus Circle, near the geographic center of Manhattan; but around it lay a cultural wasteland. Today, it is the new home of the Museum of Arts and Design (also known as MAD) which, with the Time Warner Center and a revitalized Central Park, completes the rebirth of Columbus Circle as a major destination.

The building has been many things to many people: an architectural oddity (“a die-cut Venetian palazzo on lollipops,” according to former New York Times critic Ada Louise Huxtable); a wealthy dilettante’s cultural folly; later, an empty shell; and, lastly, an object of extreme nostalgia. Stone designed the 1964 building for A&P supermarket heir Huntington Hartford’s Gallery of Modern Art, the institution he created to display his collection and promote the cause of figurative art. It was a swank, frilly rejoinder to the high Modernist impulse in art and design, then enshrined as doctrine by New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA).

But times change. Supermarket fortunes are frittered away, institutions conceived as vanity projects close, buildings are handed over to the city and then abandoned for 10 years while someone decides what to do with them.

So it was that, earlier this fall, I found myself seated in a mahogany-paneled red-and-gold auditorium, whose ceiling, a vaulted web of circular brass tiles, pays tribute to Manhattan’s only traffic circle, just outside. In this meticulous re-creation of the room Stone designed, we were gathered to celebrate the Museum of Arts and Design, reopening with a new name and an expanded mandate after an intense preservation battle and a six-year redesign. MAD’s predecessor was inaugurated in 1956 as the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, and craft—as distinct from folk art—has evolved over the past 50 years, carrying on extended flirtations with the fields of art and design, while the museum itself has expanded its global reach.

In a controversial redesign, Brad Cloepfil, founder of Allied Works Architecture, based in Portland, Oregon, has remade the building from top to bottom. He preserved its quirky, curving shape, restored its auditorium, and kept its signature ground-floor arcade of lollipop-shaped arches, enclosing them in glass. (They now offer street views into the lobby and the museum’s gift shop, which sells mostly one-of-a-kind, artisan-produced objects.) But he also removed 300 tons of concrete from the structure, sheathing its exterior in iridescent ceramic tile and perforating it with strategic cuts that flood the once-windowless galleries with natural light. Graceful light- and art-filled stairwells allow visitors to spiral between four gallery floors up to the ninth-floor restaurant, which will feature panoramic city and park views when it opens early next year. The result is a rarity, post-Bilbao—an art institution conceived from the inside out. The emphasis is not on the museum as image or spectacle, but on people’s encounters with its art—punctuated by stunning views of Columbus Circle and Central Park—as they move through it.

“It’s the interior that really generated everything you see on the outside,” Cloepfil says on the morning of the opening. “The primary focus is engagement with the art,” but the views out on all four sides “also reconnect you with the city.”

It was tempting to draw a parallel with the mission of design itself, as bridging the gap between art’s ivory tower and real-world needs. Was that what philanthropist Aileen Osborn Webb had in mind when, responding to an increasingly technology-driven society, she established the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (devoted to a “plain cousin of the fine arts,” as Time magazine called it), in a refurbished Victorian brownstone on West 53rd Street, steps away from MOMA?Craft, for her, had always had a social dimension. A decade earlier she had funded educational programs for combat veterans returning from the dehumanizing traumas of World War II, in the belief that they might find solace in metalworking. Later, at the height of the Cold War, she organized international conferences where urban designers mingled with village artisans, in hopes that craft could promote world peace.

Meanwhile, under the directorship of Paul J. Smith, who led the museum from 1963 to 1987, the institution—renamed the American Craft Museum in 1979—continued to hack away at traditional aesthetic hierarchies—between high and popular culture presenting wildly innovative shows devoted to the likes of sound installations, the art of baking, and the like.

“Whirligigs and spinning wheels” are what Holly Hotchner says most people in the mid 1990’s, when she took over as director, mistakenly assumed the museum showcased. And that was if they had heard of it at all. By then, it had outgrown its second home on West 53rd Street, but membership and attendance were stagnating.

In the search for a new name, Hotchner says, “We realized that what was meant by craft at the time of the museum’s founding—with architects, designers, artists, and craftspeople discussing how art and industry could come together—actually gave a very sound direction to our future. We’ve chosen arts, plural, meaning the arts and crafts movement, decorative arts, applied arts—the coming together of many arts and design.”

Hotchner hopes museumgoers will begin their visit on the sixth floor, with the new open-studio program, where a rotating roster of artists-in-residence will offer the public a window onto the creative process. There, on the morning of the opening in September, in one of three luminous, linked ateliers, the conceptual potter and performance artist Zack Davis was throwing tiny pots on a wheel, then cramming the still-wet forms into an attaché case. “I tried to stick with something that was true to midtown,” he said, explaining that this “dirt in a briefcase” was his impromptu response to that day’s turmoil in the financial markets.

One flight below him, Hew Locke, born in Edinburgh, raised in Guyana, and now residing in London, stood next to a fantastic trio of model ships he’d fastened together from dime-store baubles—plastic swords and shields, metal chains, Christmas decorations, artificial flowers, toy guns. Titled Golden Horde in honor of Genghis Khan’s marauding troops, the work deals with “fears of immigrants,” he explained. “But the work is also about immigrants’ dreams of streets paved with gold, and then too about my love for Baroque saltcellars and Mexican Madonnas, and my interest in a broken kind of beauty.”

Locke’s work is featured in the inaugural exhibition, “Second Lives: Remixing the Ordinary,” which runs through mid-February. It spreads out over two floors, and showcases 51 artists and designers who transform discarded or commonplace objects—from disposable chopsticks and telephone books to toothpaste tubes—into materials for creation. “For the most part, the museum’s focus has been on ceramics, glass, metal, fiber, wood—all of the standard craft mediums,” says curator David Revere McFadden, who organized the show with his co-curator, Lowery Stokes Sims. “One of the reasons to do “Second Lives,” he continues, “was to rethink the entire idea of what material means.”

Luminous chandeliers, wittily put together from cascading prescription eyeglasses (Stuart Haygarth) or hypodermic needles ominously mingling among Swarovski crystals (Laurel Roth and Andy Diaz Hope), hang from the ceiling. Michael Rakowitz’s re-creations of plundered and lost antiquities from the National Museum of Iraq, in Baghdad, made from Arabic newspapers and Middle Eastern food packaging, are uncannily moving. Tara Donovan’s ethereal sculpture of a coral reef reveals itself, upon closer inspection, to be composed of clear plastic shirt buttons, endowed by the artist with an undersea beauty.

“Increasing numbers of artists in the fine-arts world are very process-and materials-oriented,” says Sims, who came to MAD after long tenures at the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “They don’t necessarily think of themselves as craftspeople,” she explains. “They exist in the space between what we traditionally call art and craft, while craft artists are becoming increasingly theoretical and conceptual.” Take Johnny Swing’s Quarter Lounge, for example. The craft-intensive labor of soldering together some 5,250 coins that went into its creation renders the quarters worthless as money, but endows them with the values of art instead.

Art, craft, and design also rub shoulders in the third-floor display dedicated to the permanent collection, which benefits from its own gallery for the first time in the museum’s history. Take just the ceramics, for example. The works on view range from a large blue-green bowl made in 1946 by Viennese exiles and West Coast husband-and-wife potters Gertrud and Otto Natzler, whose signature crater glaze gives it the appearance of some volcanic artifact; to contemporary avant-gardist Eva Hild’s undulating abstractions in stoneware. There are pieces by fine artists—dabblers in the medium such as Cindy Sherman, whose image, disguised as Madame de Pompadour, appears on a Nymphenburg porcelain soup tureen—and lifelong potters like Betty Woodman, whose classically puffy Pillow Pitcher seems endowed with a quirky, Etruscan grace.

Just below, in the newly opened jewelry gallery (among the first of its kind in this country), the works of 1940’s Greenwich Village bohemians like Sam Kramer—a silver bird pendant, for example, set with a taxidermied eye and betraying the twin influences of biomorphism and surrealism—share space with a distinguished collection of ethnographic jewels and pieces by contemporary conceptualists such as Otto Künzli, whose ironic commentary on our fixation with precious metals takes the form of a gold bracelet entirely encased in black rubber.

With its unique mandate and location, Hotchner fully expects MAD to become a major tourist draw. The museum’s consistent focus on process sets it apart, she says. “We probably wouldn’t have a basic toaster in our collection,” Hotchner explains, “but if we did, we’d have the prototypes and the drawings, and perhaps a film of the artist talking about how it came to be and what forces at the time moved the piece in that direction—whereas MOMA’s design department would put it on a pedestal and declare, ‘this is an important toaster.’”

Still a fly in MOMA’s eye, then?That alone might reassure Huntington Hartford that his building, in MAD’s daring adaptive reuse, had not strayed too far from its original mission. And don’t underestimate the childlike fascination that the process of making things still arouses in people. “In the old days, on 53rd Street,” Hotchner recalled, “the museum used to have a weaver working at a loom in the window. And people would pile up outside to watch her.” Today, visitors to MAD can watch a contemporary woodworker on film or stand right next to the spinning potter’s wheel. Location is everything.

Direct flights to the New York City area are available through JFK, LaGuardia, and Newark airports.

Great Value 44 W. 63rd St.; 212/265-7400; empirehotelnyc.com; doubles from $399.