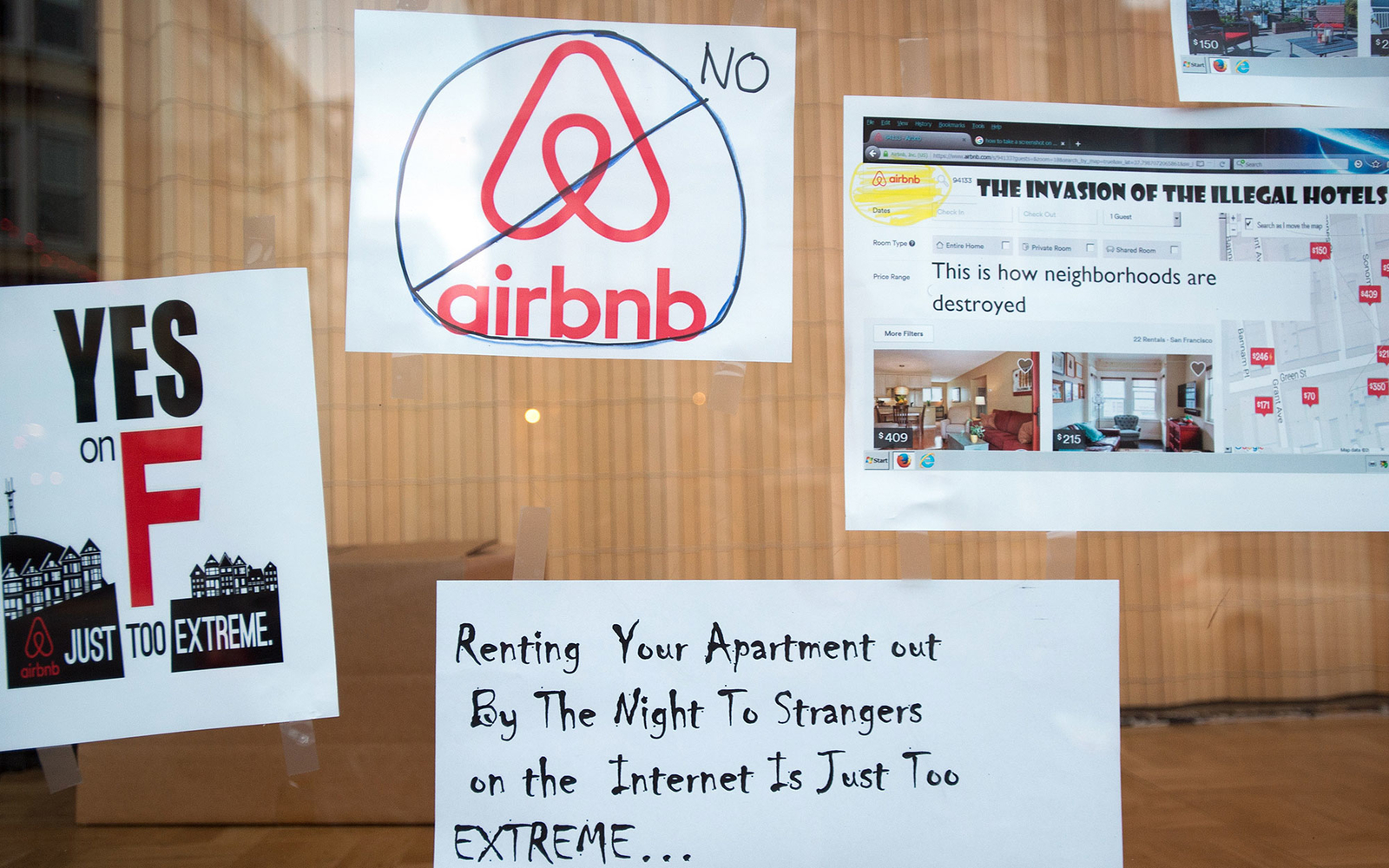

San Francisco voters will cast their ballots Tuesday on whether to restrict Airbnb and its competitors.

San Francisco is suffering from a housing crisis that has propelled rents into the stratosphere. And according to the supporters of a ballot measure to be voted on next week, the culprit is none other than home sharing service Airbnb.

The local ballot measure, Proposition F, seeks to impose a stricter limit on the number of nights landlords can rent their homes and apartments through Airbnb and other similar services.

Currently, they can rent 90 days annually if they aren’t present and an unlimited number of days if they are. But if the initiative passes, they would only be able to lease their places for 75 days, regardless of whether they are present.

Additionally, neighbors would be able to file complaints and lawsuits against landlords—and collect damages—even if the city has already cleared them of wrongdoing. Opponents, however, have attacked the possibility in their onslaught on television commercials by raising the ugly specter of neighbors spying on neighbors.

Prop F, as it is more commonly known, has arguably become the most talked about measure on this year’s ballot in San Francisco. In a city with a huge influx of tech wealth, it has become ground zero in a fight between the haves and the have-nots.

Airbnb has poured in more than $8 million of dollars into defeating the measure, which it fears could threaten its revenue in its hometown and set off a wave of similar ordinances around the country. The money has funded a series of television commercials, billboards, and stacks of direct mail.

The initiative’s supporters, on the other hand, have raised more than $482,000, of which $410,000 came from a hotel workers union. They have run a mostly shoe string campaign that has relied mostly on newspaper op-eds and online videos to spread its message.

The proposition is the brainchild of Share Better SF, the local branch of a New York City-based coalition of politicians and local groups. The organization has been fighting Airbnb and other home-rental companies like HomeAway’s VRBO in New York City, where last year, Airbnb was forced to turn over data on more than 10,000 hosts suspected of violating laws.

The proposition has also received support from local organizations and politicians, such as U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.).

Born in 2008 out of two friends’ need to rent out their apartment to help pay rent, Airbnb lets regular people rent out space in their homes for short or long stays. The company has since raised skyrocketed in value to $25.5 billion and into one of the most prominent faces of the so-called “sharing economy.”

In September, Airbnb hired Chris Lehane, a former White House advisor to Bill Clinton whose firm represented Goldman Sachs during the recession, among other clients, as its head of global policy and public affairs. The hiring signaled how seriously the company takes potential regulatory obstacles to its business, which is already under attack in a number of cities and states.

“We want to work in partnership with cities,” Lehane said in an interview with Fortune.

The debate over the proposition — and San Francisco’s overall housing crisis — is complex. But it mainly revolves around two issues.

First, is the question of Airbnb’s impact on the San Francisco’s housing. In the last few years, rents have soared while affordable housing has seemingly disappeared. Because renting out an extra room, and especially an entire unit, for a short term is a lucrative business, some San Francisco residents have done so from time to time to make a little extra money.

“Airbnb was created to keep people in their home,” Lehane told Fortune, adding that the proposition is an “attack on the middle class.”

Another set of hosts, however, use the service to rent out an entire unit or home—sometimes a second home or additional properties they own—year-round. They collect big money from renting to tourists instead of finding long-term tenants.

And it’s that second case that’s problematic, according to Prop F supporters. For the last few years, newspapers have featured articles about landlords evicting long-term residents to turn their units into Airbnb hotels and people renting second homes through the site that could otherwise house long-term residents. It’s these commercial hosts, as they’re called, that are the problem.

But, of course, there’s a lot of disagreement over how often this truly happens. In May of this year, the city issued two separate reports on the impact of short-term rentals on housing. One, from San Francisco’s Budget and Legislative Analyst, concluded that between 925 and 1,960 units were likely removed from the market because their owners listed them on Airbnb instead.

The other report, authored by the city’s chief economist, didn’t come to a definitive conclusion about short-term rentals—and Airbnb’s—impact on the strained housing stock. Although the report did find that there was likely some connection, it also said that because of a lack of data, it’s impossible to really know.

Airbnb’s own analysis, released the following month, of course, found that its business only had a negligible effect on the rental market. The company also argued that the number of vacant units in the city has remained unchanged between 2005 and 2013.

The other main topic of debate centers around zoning laws. Or, in the eyes of Prop. F supporters: San Francisco residents’ rights to a quality life in a residential area, and not a neighborhood of defacto hotels.

Proponents of ballot measure say they have no problem with homeowners having guests staying with or without them a couple of times a year. Rather, the problem arises when a steady stream of strangers comes and goes, creating noise and raising safety concerns for neighbors.

When asked about those complaints, Lehane said that Airbnb’s community does a good job at policing itself. Bad hosts and guests are naturally weeded out because they receive bad reviews and ratings by other users.

Lehane added that the company has created a hotline for neighbors to report bad behavior. However, it is difficult to find on the company’s website because it is buried in the section for hosts.

Prop. F authorizes anyone who lives within 100 feet (not just residents of the building, as the current law states), homeowners’ associations, and housing non-profits to file lawsuits to punish the most egregious landlords. They would be able to do so even without the city finding a violation under existing law, which was voted on last fall and went into effect in February.

In speaking with Fortune, Lehane pointed to a previous 30 year-old proposition dealing with clean drinking water and toxins that has been criticized for fueling private lawsuits against businesses for pollution. Many of the litigants sued solely to make money without any improvement in the environment for the community, he said.

But Share Better’s spokesman, Dale Carlson, called that interpretation an exaggeration used by Airbnb to scare voters. Filing a lawsuit involves a lot of work, he said, and that reasonable people would only do so if they have a legitimate complaint.

And it’s part of a larger point Carlson makes, which is that the city’s current rules and the new office it has set up to police short-term rentals simply aren’t effective enough to keep hosts in line. “The laws and regulations that the city has put forward have been examined by experts and they’ve determined that the laws are unworkable,” Carlson toldFortune.

This is also why Prop. F would put the burden on Airbnb and other websites to track how many days a unit has been rented and block those that have reached their limit from being listed. According to Carlson, the city government doesn’t have the resources or information to track down scofflaws. As part of the amendment to the current law that passed in July, the city has set up a new office to handle host registrations and enforce rules, but Carlson says it’s understaffed and ineffective.

Prop. F also requires hosts to report quarterly the number of days they’ve rented out their units and how many nights they’ve spent at home. It’s already required, in theory, but relatively few landlords have registered so far.

“No one is the world requires you to actually register with the government the number of nights that you’re sleeping in your own bed,” Lehane says, which he described as draconian. Even Taliban and ISIS don’t go to such lengths in the Middle East, he said.

Airbnb argues that it has no way of knowing if a unit has been listed and rented out through a different service. The company has also been opposed to sharing this data with city officials, stating concerns over its users’ privacy.

Still, the debate over home-sharing services like Airbnb and VRBO is just as complex as the housing crisis itself. Tuesday’s vote marks just the latest incarnation—the first referendum on Airbnb itself.

More good reads from Fortune:

• Protesters occupy Airbnb HQ on eve of San Francisco vote

• Amazon Is Opening An Actual, Real-Life Bookstore

• See China’s first jet that will compete directly with Boeing’s 737