David Nicolas

The Lincoln Highway, which once stretched from coast to coast, invited drivers to see the U.S.A. in their Model A's. Jeff Wise ponders the manifest destiny of car travel, and the road ahead

David Nicolas

The Lincoln Highway, which once stretched from coast to coast, invited drivers to see the U.S.A. in their Model A's. Jeff Wise ponders the manifest destiny of car travel, and the road ahead

It started at a Los Angeles flea market. I was foraging casually through rows of card tables when I spied a book of old postcards: ALONG THE 'LINCOLN HIGHWAY.' The pictures showed scenic spots on a road that didn't look like a highway. It was more a two-lane blacktop, not even a line down the middle.

I was curious enough to pay $5 and take the postcards home, where a few minutes on the Internet revealed the significance of my find. I had stumbled upon a souvenir of the first road that went all the way across the United States—the granddaddy of the American highway system. The more I investigated, the more intrigued I became. Finally, I just had to drive it. At least, the rugged, westernmost thousand miles of it, in a trip that would turn out to be half wilderness adventure, half time travel. The road, which had been state-of-the-art 90 years earlier, would prove more primitive than I could have imagined—a blunt revelation about how much the nation and its transportation system had changed in a century. If the next 90 years bring anything like the same kind of transformation, the future will hardly be recognizable.

Our restless nation has grown ever more restless over the years, zooming from here to there at airplane velocity. Dirt roads gave way to gravel, gave way to blacktop, gave way to the interstate system, where everything is sacrificed in the name of speed. These days, you can cross entire states in the time it would have taken someone to drive just a few miles in the early 1900's. It's difficult to believe now, with the open highway such a defining facet of our American identity, but at the turn of the last century there were no paved roads outside cities and towns. Anyone going any distance at all went by train. Traveling across the United States by car made as much sense as going by pogo stick.

But by the teens, some forward-thinking minds were beginning to envision a bright future for the horseless carriage. (Some preferred the more sophisticated French term, automobile.) One of the biggest dreamers was Carl Fisher, who in 1909 had paved a racetrack with bricks in his hometown and called it the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. He also owned the Prest-O-Lite headlight company, and he knew that Americans wouldn't embrace automobiles (or headlights) until they had somewhere to drive. What the country needed was a road, a road paved all the way across the continent, from Times Square to the Golden Gate. Sure, it was crazy, like saying you were going to put a man on the moon, but Fisher knew that only a grand scheme would capture the public imagination.

Underneath all the hype, however, Fisher was a realist—he knew that no one could actually build such a road. His plan was to mark a route across the country and cajole communities along the way to improve their sections. For the time being it would be what were called natural roads (really just unimproved dirt).

When the route was officially announced in September of 1913, the country lapped it up. In the days before extreme adventure vacations, the Lincoln Highway—less a "highway" than a cobbling together of farm roads and stagecoach trails—was a thrilling romantic challenge, a sort of automotive Mount Everest. Many songs, articles, and books were written about it, including a volume by Emily Post (who got as far as Cheyenne, Wyoming, before giving up and turning south).

Eventually, though, the Lincoln Highway fell victim to its own success. In the mid twenties, the federal government introduced interstate highways, and the Lincoln was split up among newly designated numbered roads. Today, most of the Lincoln Highway lies buried under, or decaying alongside, at least a dozen modern routes. But in the far West, much of the road between Utah and Nevada was bypassed by later development, and some 150 remote miles of it remain unpaved. I flew to Salt Lake City, ready for the worst the old relic could throw at me.

My timing was not great. It had been raining all week when I arrived in Salt Lake, and by all accounts the dirt road would be in bad shape. I waited for the rain to end and began my trek the next morning, keeping an eye out for the original roadway. Near the mining district of Flux, I caught my first glimpse of it: a narrow strip of crumbling pavement that ran alongside the newer asphalt state road for a mile or so. A few miles farther on, where the Lincoln Highway curved south into Skull Valley, I found a muddy, potholed track, barely wider than my rented Ford Explorer, running through the sagebrush. I veered off the modern road and plowed along it for a few miles, drenching the windshield with mud.

Such sections, I found, are never drivable for long. Unprotected for 80 years, the weathered road has suffered any number of indignities: being buried under newer roads, fenced off by private land, washed away, or simply grown over. Forty miles past Flux, I reached Orr's Ranch, once a major stopping point. Now, as it was then, it's a working farm, a motley collection of outbuildings and ramshackle fences that sprawl under the serene snowcaps of the Stansbury Mountains. A long section of the original highway is still in use as an access road, and you can see the log cabin where travelers were once fed and lodged.

After a pit stop, I was tearing across the basin, enjoying clear skies and open country. When they laid out the road across central Utah, the Lincoln Highway Association chose to follow the general route of the old Pony Express. Thanks to the enthusiasm of modern-day tourists, a broad, well-maintained gravel road now overlies both bygone routes. The old stage stations are still there, mostly reduced to crumbling cairns surrounded by chain-link fence: Simpson Springs, Boyd Station, Canyon Station. I stopped at each to stretch my legs and savor the lonesomeness that such a posting must have entailed. This is basin-and-range country, an endless alternation of upthrust ridges and flat seas of sagebrush. The air was so clear, the vista so wide, that it deceived the eye; a valley that looked a mile across turned out to be 10. I encountered only one other car, driven by a dusty-looking fellow who stopped to chat as we drew alongside each other; turns out he was a geode prospector, coming from his claim.

The sun was slinking toward the mountains as I arrived at Fish Springs, once a ranch owned by a legendary codger, John Thomas. A sign out on the salt flats read, IF IN NEED OF TOW, LIGHT FIRE. Back in the day, folks would bog down, put a match to a pile of brush, and out Thomas would come with his draft horses. He'd size them up, quote a price—a dollar a foot was the norm—and if they didn't like his rate, he'd keep raising it until they agreed. Today Fish Springs is a National Wildlife Refuge, overseen by ranger Jay Banta, the Utah director of the current Lincoln Highway Association. Jay took me to a pristine section of the 1913 road. "The Pony Express is so romanticized, but all it proved was that mail couldn't profitably be moved overland," he said. "The Lincoln Highway kicked off the whole concept of automobile touring."

The next day, I passed through the remote community of Callao, Utah, where Kearney's Ranch hotel still sits by the side of the road like an empty ghost. I then crossed over Schellbourne Pass to the Steptoe Valley, hitting asphalt again on U.S. 93 in Nevada. Forty miles south, in Ely, I picked up Highway 50, which roadside signage touts as THE LONELIEST ROAD IN AMERICA. Every few minutes another car or truck passed. After the solitude of the Pony Express Trail, it felt like Mardi Gras. From time to time I thought I could spy traces of the old highway: a dirt track winding through the hills around me.

Small towns along the way testified to the cyclical nature of Nevada's mineral wealth. In Eureka, I knocked on the door of the Jackson House Hotel, an 1880 brick edifice that stands alongside the grand Eureka Opera House. Too late: it had closed two weeks before. "Not enough business," said the proprietor of the restaurant across the street, "since the mines laid off a thousand people last December." (It turns out the hotel closes during the winter, but opens again come spring.) In the threadbare mountain town of Austin, 70 miles up the road, I peeked into the splendidly creaky International Café, a former hotel shipped in its entirety from Virginia City, Nevada, in 1863. Two of the three mirrors over the ornate bar are original; the third was shattered long ago by a bullet that had passed through the skull of a patron.

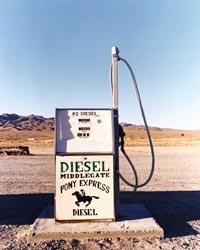

If jobs were scarce, enthusiasm for the Lincoln Highway was not. At the hamlet of Middlegate I chatted with Russ and Fredda Stevenson, owners of the Middlegate Station honky-tonk, who invited me to drive the mile-long stretch of original Lincoln Highway on their property. As I crossed the California border and passed through the mountain town of Truckee, I remembered something that Jay Banta had told me: "Someday I'm going to drive the whole highway in a Model A," he said, "meeting nuts like me along the way."

After three days in the desert, I thought the forests of the Sierra Nevada were paradise. The first drivers must have felt the same. When they crossed into California, the hard part of their journey was behind them. It was just a couple of hundred miles to the highway's end in San Francisco, all of it well paved. One traveler who rode the Lincoln Highway in 1919 noted appreciatively, "Entire route down grade over bitumen surfaced concrete roads lined with palm trees, through peach, orange, and olive ranches and vineyards." (Californians have always loved their asphalt.) The old road is not just remembered here, it's celebrated—you can still find streets called Lincoln Way or Lincoln Highway. In Auburn, a historic mining city in the Sierra foothills, Lincoln Highway markers are posted along the route at almost every intersection.

Descending into the Central Valley, I was sucked into the maw of the California superhighway system and propelled southward like a jet. Blinkered by concrete walls on either side, I was making good time but had no idea where I was or whether I was passing through farmland or desert. Then I hit bumper-to-bumper traffic and within an hour, I was fighting my way over the Bay Bridge at rush hour. By the time I reached a friend's house downtown, I was exhausted.

The next morning I drove from the Castro to Lincoln Park,near the Golden Gate Bridge. The official end point lay near the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, a fine-arts museum. A marker once stood in front of the museum, near where a blue-tiled fountain sputters today. I assumed that it had long since vanished, but then I saw it off to the side, near a bus stop overlooking a golf course: WESTERN TERMINUS, LINCOLN HIGHWAY.

What I felt must have been a hundredth of the bittersweet emotions those words no doubt brought to adventurers who endured mud, rain, breakdowns, and weeks on the road to read them (my journey took only four days). Looking around at the people strolling about, I couldn't imagine that many ever noticed the tiny obelisk, let alone understood its significance. And if they did, I doubted they knew the vastness it demarcated, the toil and patience it implied. I stayed for a few minutes, gazing out over the golf course. Then I got back in the car and drove away.

JEFF WISE is a contributing editor for Travel + Leisure.

THE FACTS

WHERE TO STAY

Peery Hotel DOUBLES FROM $129. 110 W. BROADWAY, SALT LAKE CITY; 800/331-0073 OR 801/521-4300; www.peeryhotel.com

Truckee Hotel DOUBLES FROM $125. 10007 BRIDGE ST., TRUCKEE, CALIF.; 800/659-6921 OR 530/587-4444; www.truckeehotel.com

Fish Springs National Wildlife Refuge Campsites nearby. UTAH; 435/831-5353; fishsprings.fws.gov

HIT THE ROAD

Lincoln Highway Association Twelve state chapters across the country. 815/456-3030; www.lincolnhighwayassoc.org

READING LIST

The Lincoln Highway: Main Street Across America, by Drake Hokanson (University of Iowa Press, $21); www.amazon.com

A Complete Official Road Guide of the Lincoln Highway, Fifth Edition (The Patrice Press, $23); www.patricepress.com