From the early 19th century through the end of the Vietnamese monarchy in 1945, Hue’s Imperial City (23 Thang 8, 7am-5:30pm daily, VND150,000) housed an impressive cache of temples, palaces, and administrative buildings belonging to the 13 kings of the Nguyen dynasty. On the northern side of the Perfume River, the walled Citadel complex reached a total of 148 buildings during its prime, most of which were constructed between 1802 and 1832. Today 20 remain, making for a captivating sight. Wide, opulent palaces and dimly lit temples pepper the now-overgrown grounds, boasting a mix of traditional Vietnamese architecture, vibrant lacquered woodwork, and ornate rooftops, not to mention 143 years’ worth of imperial history.

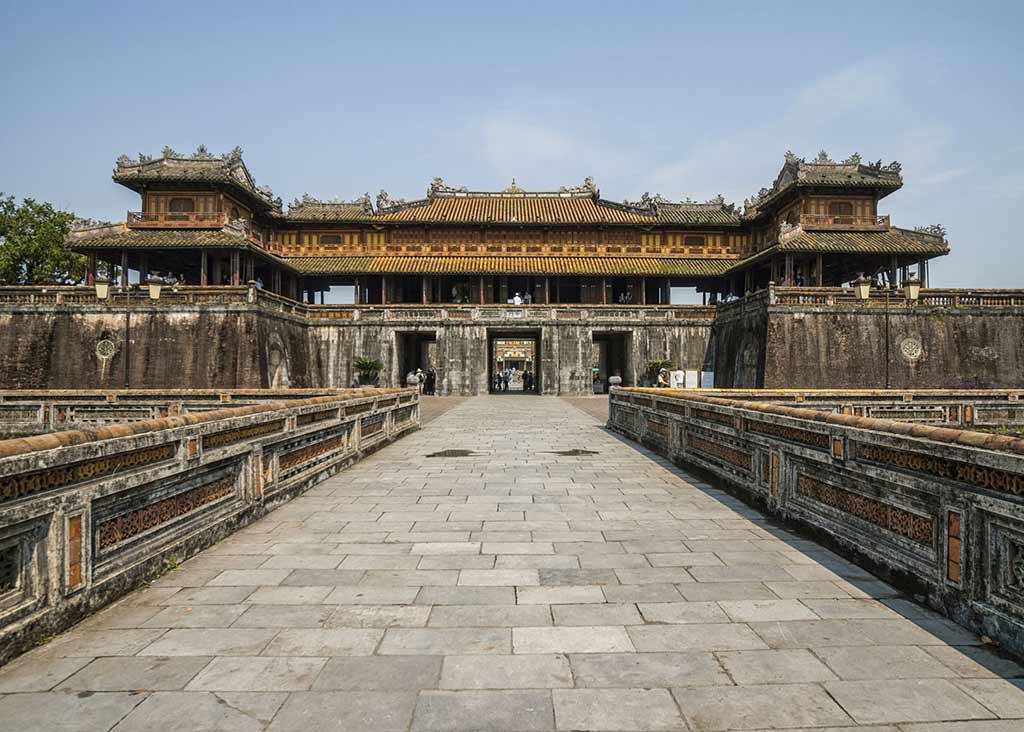

The Imperial City Gate. Photo © Dana Filek-Gibson.

English-speaking guides are in high demand, so call the Hue Monuments Conservation Center ahead of time to reserve a guide.Avoid heat and crowds by turning up in the early morning. Allot at least 1.5 hours to explore this sight at your own pace; there is a fair bit of ground to cover and you’ll likely want to stop and take photos or rest at some point. Electric car services are available, as are tour guides (VND100,000). English-speaking guides are in high demand, so call the Hue Monuments Conservation Center (23 Tong Duy Tan, tel. 05/4351-3818, 7am-5:30pm Mon.-Fri.) ahead of time to reserve a guide. Guides hired at the Imperial City tend to lead only a “greatest hits” tour, skipping the mostly destroyed Forbidden Purple City and the Thai Binh Reading Pavilion to swing by the Mieu Temple Complex, and can sometimes push hard for a tip. Hiring a guide is not a bad option for someone who has time constraints and a limited budget, but if you’re looking to get the whole story then you’re better off arranging a private guide or hopping on a public tour with a more knowledgeable leader.Before you pass through the enormous Ngo Mon Gate (Noon Gate), take a moment to look toward the equally huge flag tower flying Vietnam’s colors on the opposite side of the road. This tower is Hue’s most recognizable icon. The massive three-tiered stone structure has been around since 1807 and is as much a symbol of the city and central Vietnam as anything else within the Citadel complex.

Ngo Mon Gate. Photo © Caludine Van Massenhove/123rf.

To enter the Imperial City, visitors cross over a small moat and go through one of the five doors at Ngo Mon Gate. In addition to providing access to the administrative buildings and living quarters of the royal family, the top of this structure was once reserved for the king during special ceremonies and Lunar New Year celebrations. In the days of the monarchy, the pavilion was reserved strictly for men; no women were permitted to ascend its stone steps until the tail-end of the Nguyen dynasty, when emperor Bao Dai invited his queen to stand beside him. Below, each of the gate’s five doors granted access to a different group of individuals, with the central opening kept strictly for royalty, the two beside for civil and military mandarins, and the far doors used for elephants.

On the other side of Ngo Mon is the Salutation Court, a large open space often used for royal celebrations, such as birthdays, as well as the twice-monthly Grand Audience, an event in which the king and all high-ranking mandarins gathered within the Imperial City. Beyond a rectangular fishpond, the clearing’s three levels were used to organize civil and military mandarins into their respective ranks, lining up single-file beside the miniature stelae bordering either side of the courtyard today. Lesser members of the royal family, relatives of the Queen Mother, for example, were relegated to the back, near the entrance; soldiers, horses, and elephants took up the pair of green lawns beside the stone courtyard.

At the far end of the Salutation Court is Thai Hoa Palace, the Imperial City’s largest and best-preserved structure. Wide and rectangular, this double-roofed building holds the original throne of the Nguyen dynasty. Its exterior, decorated with yin-yang tiles and vivid mosaic facades, captures the spirit of the Imperial City’s heyday. Inside, the palace’s pair of roofs are bolstered by 80 solid ironwood columns lacquered in red and gold. Up above, decoration alternates between a series of poems and picture characters just below the ceiling. The building, completed in 1805, has undergone major renovations twice, in 1833 and again in 1923, and now stands as the most intact structure in the complex.

At the center of Thai Hoa’s main room, the royal throne might not be the grand seat of the empire you might expect, but this small chair made of red-and-gold lacquered wood was used from the reign of Gia Long, first emperor of the Nguyen dynasty, all the way through to Bao Dai, its last. The throne sits upon a platform with three levels, symbolizing the relationship between human beings, heaven, and earth, and is covered by a decorative canopy that hangs over the platform.

Beyond the royal throne, the second room of the palace offers an informational video about the history of the Imperial City that’s worth a watch, as well as a model of what the Citadel looked like in its prime. This gives an idea of the grandeur of the complex before much of it was destroyed by the conflicts of the late 20th century.

After you’ve wandered through Thai Hoa Palace, you’ll exit onto the sunny grounds bordered by the Right and Left Houses. While their functions have changed considerably—one is now an exhibition hall, the other a photo studio where guests can dress up in imperial garb for portraits on a replica of the throne—these buildings were once the offices of the Nguyen dynasty’s civil and military mandarins.

Excerpted from the First Edition of Moon Vietnam.