On November 6, 1849, a sailing ship made port in Hamilton carrying 58 men, women, and children—the first Portuguese immigrants to Bermuda. “We sincerely trust this importation of laborers will answer the end contemplated,” read a dispatch in The Royal Gazette, “and we hope they will be the means of inducing the cultivation of the wine more extensively than at present.”

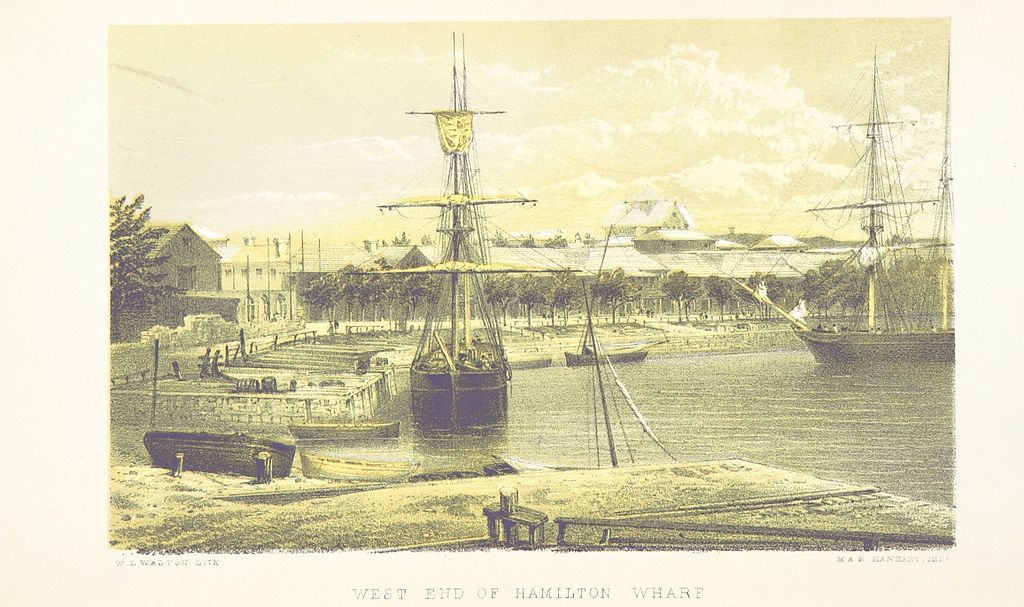

Depiction of the west end of Hamilton Wharf circa 1857. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Vineyards never did become a thriving enterprise in Bermuda, but those first farm workers from the island of Madeira were the vanguard of waves of Portuguese immigration to the island. Their journey would be repeated by thousands of Portuguese, mostly from the remote Azores Islands, who headed to Bermuda to fill a dire need for agricultural expertise and carve out a better life for themselves. Their efforts paid off, and farming—and the export of onions, arrowroot, tomatoes, and other products—became a lucrative economic generator for the island in the second half of the 19th century. Today, as lawyers, bankers, and tenacious entrepreneurs, generations of Portuguese Bermudians have called the island home; their community makes up an estimated 25 percent of the population.

It wasn’t always smooth sailing for Portuguese immigrants. Bureaucratic and social discrimination relegated them to the status of second-class citizens, even into the 1960s and 1970s. Strict government regulations attempted to bar the immigration of whole families and restricted job classes to menial labor. Like blacks until desegregation in the 1960s, the Portuguese were banned from many of the island’s social clubs. But the community was a strong and self-supportive one; established Portuguese helped new immigrants find their footing and lobbied for their rights. In the 1980s, the Portuguese-Bermudian Association pressed the case of long-term residents, including numerous Portuguese who had lived or even been born in Bermuda but had no legal right to stay on the island. The group’s efforts finally nudged the government to grant long-term residency to many people of all nationalities who have made a significant contribution to Bermudian society.

Portuguese Bermudians keep their culture vibrantly alive on the island, linking the island to the vast diaspora of Portuguese civilization around the world. Their club, the Vasco da Gama Club (51 Reid St., Hamilton, tel. 441/292-7196), has been a social and political hub for both new immigrants and later generations. Portuguese is now considered a second language on the island, and in recent years, government departments, banks, and some businesses have begun to provide translated signs and customer information on official forms, websites, and in retail centers. The Portuguese Cultural Association promotes beloved age-old traditions by teaching dances, cooking, and other arts to younger generations, who perform at national events such as the May 24 Bermuda Day Parade.

![St. Theresa's Cathedral in Hamilton, Bermuda. By Concord (Own work) [<a href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0">CC BY-SA 3.0</a>], <a href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ASt._Theresa's_Cathedral_exterior.jpg">via Wikimedia Commons</a>.](https://www.holidaytravel.cc/Article/UploadFiles/201602/2016021614454262.jpg)

St. Theresa’s Cathedral in Hamilton, Bermuda. By Concord (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Religious festas also make colorful public spectacles throughout the year, with ornate costumes and processions in which church elders and citizens walk on carpets of petals to celebrate important Roman Catholic saints and the Holy Trinity. In the procession of Santo Cristo, held on the fifth Sunday after Easter, hundreds gather at St. Theresa’s Cathedral in Hamilton for a solemn march through the city’s streets to seek miracles for the sick and needy. In June, Portuguese Bermudians celebrate the Festa do Espiritu Santo (Festival of the Holy Spirit) in King’s Square, St. George. An elaborate pageant paying tribute to the legendary charity of Queen Isabel includes a feast for participants who are served bowls of sopa (soup) and pao dolce (sweet bread).Portugal has established a Portuguese Consulate office in Bermuda (Melbourne House, 11 Parliament St., Hamilton, tel. 441/292-1039), headed by Honorary Consul Andrea Moniz DeSouza, an associate lawyer who works as a liaison between the Bermuda and Portuguese governments and the Portuguese national community.

Excerpted from the Fourth Edition of Moon Bermuda.