The Cathedral at Havana August-September 1762 by Dominic Serres the Elder. Photo courtesy of the London’s National Maritime Museum.

In 1762, the English captured Havana but ceded it back to Spain the following year in exchange for Florida. The Spanish lost no time in building the largest fortress in the Americas—San Carlos de la Cabaña. Under the supervision of the new Spanish governor, the Marqués de la Torre, the city attained a new focus and rigorous architectural harmony. The first public gas lighting arrived in 1768, along with a workable system of aqueducts. Most of the streets were cobbled. Along them, wealthy merchants and plantation owners erected beautiful mansions fitted inside with every luxury in European style.

By the mid-19th century, Havana was bursting its seams. In 1863, the city walls came tumbling down, less than a century after they were completed. New districts went up, and graceful boulevards pushed into the surrounding countryside, lined with a parade of quintas (summer homes) fronted by classical columns. By the mid-1800s, Havana had achieved a level of modernity that surpassed that of Madrid.

Following the Spanish-Cuban-American War, Havana entered a new era of prosperity. The city spread out, its perimeter enlarged by parks, boulevards, and dwellings in eclectic, neoclassical, and revivalist styles, while older residential areas settled into an era of decay.

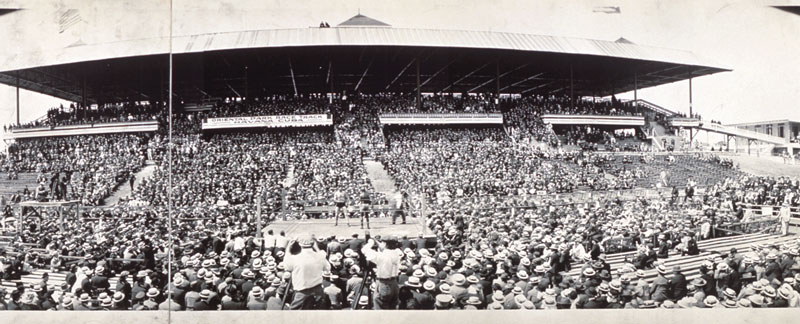

A boxing match (Willard vs Johnson) held in Havana in 1915. Photo in the public domain, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

By the 1950s Havana was a wealthy and thoroughly modern city with a large and prospering middle class, and had acquired skyscrapers such as the Focsa building and the Hilton (now the Habana Libre). Ministries were being moved to a new center of construction, the Plaza de la República (today the Plaza de la Revolución), inland from Vedado. Gambling found a new lease on life, and casinos flourished.

Following the Revolution in 1959, a mass exodus of the wealthy and the middle class began, inexorably changing the face of Havana. Tourists also forsook the city, dooming Havana’s hotels, restaurants, and other businesses to bankruptcy. Festering slums and shanty towns marred the suburbs. The government ordered them razed. Concrete high-rise apartment blocks were erected on the outskirts. That accomplished, the Revolution turned its back on the city. Havana’s aged housing and infrastructure, much of it already decayed, have ever since suffered benign neglect. Even the mayor of Havana has admitted that “the Revolution has been hard on the city.”

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of poor peasant migrants poured into Havana from Oriente. The settlers changed the city’s demographic profile: Most of the immigrants were black (as many as 400,000 “palestinos,” immigrants from Santiago and the eastern provinces, live in Havana).

Finally, in the 1980s, the revolutionary government established a preservation program for Habana Vieja, and the Centro Nacional de Conservación, Restauración, y Museología was created to inventory Havana’s historic sites and implement a restoration program that would return much of the ancient city to pristine splendor. Much of the original city core now gleams afresh with confections in stone, while the rest of the city is left to crumble.

Excerpted from the Sixth Edition of Moon Cuba.