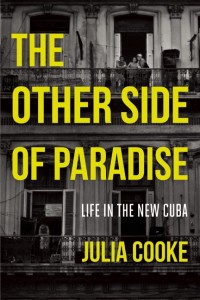

$17 | Seal Press

ISBN: 9781580055314

More recently, I had the opportunity to interview Julia.

Julia Cooke: I first went because, well, anything you weren’t supposed to do was appealing. Actually, a good friend of my father was doing business legally with Cuba, selling food. I accompanied him to Havana for my twentieth birthday as a translator during his business meetings. I was well traveled—my father was an airline executive—but the experience was bizarre. Everything about Havana was strange and exhilarating. It was unlike anything I’d ever experienced. It was constantly engaging.

JC: 2003. I stood on the balcony of my casa particular (private room rental) and watched the street life and felt like I belonged here. I plunged directly in. I took a semester off from university and found a study-abroad program in Havana. I spent ten months in Cuba during three stints, with breaks in-between.

JC: I was studying on San Lázaro, in Centro Habana. As you know, that part of Havana is awesome. It was full of life, vibrant, non-stop, amid the decay. I rented an apartment on the edge of Miramar near Linea, close to the maquina [old collective taxis] line.

JC: It was coming back to the United States that made me want to write a book. There wasn’t a book that helped me unlock the experience. I was disappointed with the portrayals of the Cuba I’d come to know. I wanted to write a book I’d want to read.

JC: I was back there in January. Part of the reason for the book was to catch Cuba in a moment of time. My heart would break if I had to cease going back.

JC: Many of the people I knew have already left Cuba. The way in which they leave isn’t predictable. Many do so in a quixotic way. Some make peace with the fact that the Cuban system can’t provide. The yearning to leave is universal, but there’s something else. Now that Raúl has lifted travel restrictions and Cuba has opened up to the rest of the world, it’s clear that the yearning to leave has changed from an economic rationale to a quest to explore abroad. Many people I write about in the book are eager to know the world at large. The tides are turning. For example, younger Cuban-Americans born in the States don’t feel the same way about Cuba as their parents.

JC: No. There needs to be more fundamental changes for people to feel hope. So far, it’s not enough for the people I’ve come to care about.

JC: Absolutely! They offer me advice. They chastise me! My real mother thinks it’s wonderful that I have so many mothers in Cuba. One of the qualities that’s so unique is the deep sense of community, of bonds that run deep. They deserve everything good in the entire world.

JC: Absolutely, if someone makes me an offer I can’t refuse [laughs]. It captured my heart from the beginning. I hope I’ll never stop going. I have no Cuban blood, but it feels like home to me.

JC: No, never! Cuban men are so flirtatious, it just becomes so sweet and tender and not serious. It’s not chauvinistic, but it takes some getting used to.

JC: My boyfriend noted that! I love how improvisatory Cubans are. It forced me out of my comfort zone. They live such a moment-by-moment life, seizing opportunity whenever and wherever it arises. They don’t get too upset about anything. I hope I’ve taken those lessons to heart.

JC: Yes… I left for Cuba after my boyfriend and I had been dating for only a few weeks. I went to Cuba and didn’t hear from him for a while. Then he came to visit, and he came to understand my passion. He was empathetic. Cuba is such an important place for me. He now understands my intellectual project and how it has consumed so much of me, and he understands the emotional pull Cuba has on me. Our relationship would be very different if he hadn’t come to Cuba.