Rock Island State Park’s beaches might be chilly, but they’re undeniably beautiful. Photo © Joshua Mayer, licensed Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike.

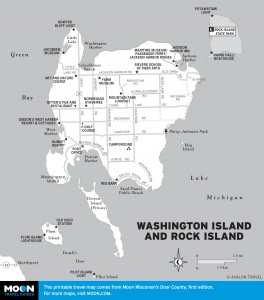

Washington Island and Rock Island

Less than a mile from Washington Island’s Jackson Harbor is one man’s feudal estate turned overgrown state park. Getting to Rock Island State Park (920/847-2235), the most isolated state park in Wisconsin’s system, necessitates two ferry rides. When you get here, it’s a magnificent retreat: a small island, yes, but with delicious solitude, icy but gorgeous beaches, and the loveliest starry skies and sunrises in Wisconsin.Native Americans lived in sporadic encampments along the island’s south shore from 600 BC until the start of the 17th century. Around 1640, the Potawatomi people migrated here from Michigan; their allies, the Ottawa, Petun, and Huron people, followed in the 1650s, fleeing the threat of extermination at the hands of the Iroquois. The Potawatomi were visited in 1679 by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, whose men built two houses, the remains of which are still visible amid the weed-choked brambles off the beach. Eventually, the French and the Potawatomi returned, establishing a trading post that lasted until 1730. Until the start of the 20th century, the island was alternately a base camp for fishers and the site of a solitary sawmill. Rock Island is thus arguably the true “door” to Wisconsin, and a ready-made one at that—the first rock on the way across the temperamental lake from Mackinac Island. Note that water is available here, but that’s all; you have to bring everything you’ll need and pack it all out when you leave.

Here’s why the isolated island is so great: There are no ticks, no pesky raccoons, no skunks, and no bears—no perils for backpackers. The worst thing is the rather pernicious fields of poison ivy (though these are usually well marked). There are white-tailed deer, lemmings, foxes, and a few other small mammals and amphibians. Plenty of nonpoisonous snakes can also be seen.

The northern hardwood forest is dominated by sugar maples and American beeches; the eastern hemlock is gone. The perimeters have arbor vitae (white cedar) and small varieties of red maple and red and white pine.

Two of the most historically significant buildings in Wisconsin, according to the Department of the Interior, are Thordarson’s massive limestone Viking Hall and boathouse. Patterned after historic Icelandic manors, the structures were cut, slab by slab, from Rock Island limestone by Icelandic artisans and workers ferried over from Washington Island. Only the roof tiling isn’t made from island material. That’s a lot of rock, considering that the hall could hold more than 120 people. The hand-carved furniture, mullioned windows, and rosemaling detail, including runic inscriptions outlining Norse mythology, are magnificent.

The original name of Rock Island was Potawatomi Island, a name that lives on in one of the original lighthouses in Wisconsin, Pottawatomie Light, built in 1836. The original structure was swept from the cliffs by the surly lake soon after being built but was replaced. Unfortunately, it’s not open to the public except for ranger-led tours. The area is accessible via a two-hour hike.

On the east side of the island are the remnants of a former fishing village and a historic water tower that’s on the National Register of Historic Places. The village dwelling foundations lie in the midst of thickets and are tough to spot; there are also a few cemeteries not far from the campsites. These are the resting places of the children and families of lighthouse keepers and even Chief Chip-Pa-Ny, a Menominee leader.

Otherwise, the best thing to do is just skirt the shoreline and discover lake views from atop the bluffs, alternating at points with up to 0.5 miles of sandy beach or sand dunes. Near campsite 15, you’ll pass some carvings etched into the bluff, made by Thordarson’s bored workers.

With more than 5,000 feet of beach, you can find somewhere to be alone, although the waters are chilly and currents are dangerous. At one time a sawmill buzzed the logs taken from the island; the wheel-rutted paths to the mill turned into rough roads. Thordarson let them grow over during his tenure on the island, but today they are a few miles of the park’s 9.5 miles of hiking trails. The island is only about 900 acres, so you’ll have plenty of time to cover it all if you’re spending more than an afternoon. On a day trip, you can cover the perimeter on the 5.2-mile Thordarson Loop Trail in just under three hours. You’ll see all the major sights and a magnificent view on the northeast side—on a clear day you can see all the way to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. For those less aerobically inclined, head for the Algonquin Nature Trail Loop, at most a onehour hike. The other trails on the island are essentially shortcuts to cross the island and are all approximately one mile long.

No wheeled vehicles are allowed in the park. The dock does allow private mooring for a fee of $1 per foot.

The camping at Rock Island is absolutely splendid, with sites strung along a beachfront of sand and, closer to the pier, large stones. Many of the sites farthest from the main compound are fully isolated, almost scooped into dunes and thus fully protected from wind but with great views (site 13 is a favorite). The island has 40 primitive campsites, all reservable, with water and pit toilets: 35 to the southwest of the ferry landing, and another 5 isolated backpacker sites spread along the shore farther southeast. Two additional group campsites are also available. Reservations (888/947-2757, $10 reservation fee, $17-20 sites for nonresidents) are a good idea in summer and fall, and essential on weekends during those times.

Note that the park is pack-in, pack-out, so plan wisely.

If you’re not kayaking over, the Karfi (920/847-2252) has regular service; the name means “seaworthy for coastal journeys” in Icelandic, so fear not. Boats depart Jackson Harbor on Washington Island daily May 25-mid-October, usually Columbus Day; the boat leaves hourly 10am-4pm daily in high season (late June-Aug.) with an extra trip at 6pm Friday. Round-trip tickets cost $10 adults and $12 for campers with gear. In the off-season you can arrange a boat, but it’s expensive.

Private boats are permitted to dock at the pier, but a mooring fee is charged.

Excerpted from the First Edition of Moon Wisconsin’s Door County.