The North Fork Valley spans diverse habitats from grassland prairies to alpine glaciers. It’s home to an immense range of wildlife—huge grizzly bears to tiny pygmy shrews. Spruce trees 300 years old root the valley in deep history. Surrounded by thick subalpine fir forests, Bowman and Kintla Lakes have miles of empty shoreline dotted with only boats of anglers or a few kayaks. Trails from the North Fork see only a few people, even in high season. Wildlife watchers can find animals and birds at the northernmost and southernmost fringes of their habitats. Nothing chills the soul quite like the wild call of wolves in the dead of night.

Trails from the North Fork see only a few people, even in high season. Pictured is the Quartz Lake Loop in June. Photo © Becky Lomax.

The North Fork is unique. It’s a small, intimate community that prides itself on its rustic nature. Not L.L. Bean squeaky-clean cookie-cutter rustic, but real bucolic earthiness with no electricity and few phone lines. Generators and propane tanks provide lights and power, along with some solar energy. The population of the four-mile-wide floodplain comprises year-round residents living off the grid and summer cabins. Most residents roll their eyes at visitors who complain about the North Fork Road’s dust and potholes; talk of paving raises the hackles of many, who don’t want to see the North Fork changed.

The hub of valley life is the Polebridge Mercantile, where residents catch up on news, sometimes not much differentiated from gossip. The town’s dogs run amok and lounge on the front porch. However, visiting canines must be leashed. Hand-painted signs will tell you so: “Local dogs at large.” One of the warning signs on the Northern Lights Saloon claims, “Unleashed dogs will be eaten.”

Smell freshly baked pastries when you walk into Polebridge Mercantile, this historic hub of the North Fork Valley. Photo © John Mayer, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

As of late 2014, the North Fork Watershed Protection Act prohibits mining and natural resource extraction in the sensitive region. The North Fork area contains all five of Glacier’s ecosystems: grassland prairies, aspen parklands, montane forests, subalpine, and alpine tundra. Rich floodplains teem with wildflowers, berries, shrubs, and trees. Fens abound with orchids, bladderworts, sundews, mosses, sedges, ferns, and bulrushes. McGee Meadows, which is actually a fen, houses at least 50 species of flora. The valley is rife with grizzly and black bears, moose, coyotes, mountain lions, and elk—all manner of wildlife down to its tiniest mammal, the pygmy shrew, which preys on 25 species of bugs, insects, and snails. Birders have documented 196 species of woodpeckers, owls, raptors, waterfowl, and songbirds, over half of which nest here.

With the natural migration of wolves from Canada in the 1980s, Glacier saw its first wolf pack in 50 years, with its first litter of pups in 1986. Numbers have since rebounded. Now wolf packs range across Montana, which has prompted controversy over their status as an endangered species. But don’t expect to see a wolf around every tree; their numbers vary year to year, they roam up to 300 square miles, and they are elusive. But you may hear them—especially at night. High concentrations of deer and elk make the North Fork Valley prime wolf habitat; to maintain its health, a wolf must eat 10 percent of its body weight in meat every day.

Years of fire suppression policies led to thick lodgepole stands and bug infestations. The 38,000-acre Red Bench Fire in 1988 saw policy change when the fire was allowed to run its natural course. Silver sentinels stand as a reminder that Polebridge was nearly wiped off the map. In 2001, the Moose Fire shot over Demers Ridge, burning 71,000 acres, over one-third inside Glacier. In 2003, the Wedge Canyon Fire burned 53,315 acres, jumping the North Fork River into the park and traveling up the side of Parke Peak, while the Robert Fire burned the valley’s south end. Evidence of each of these fires is obvious, but swift new growth is building a new forest blooming with fireweed, arrowleaf balsamroot, and lupine.

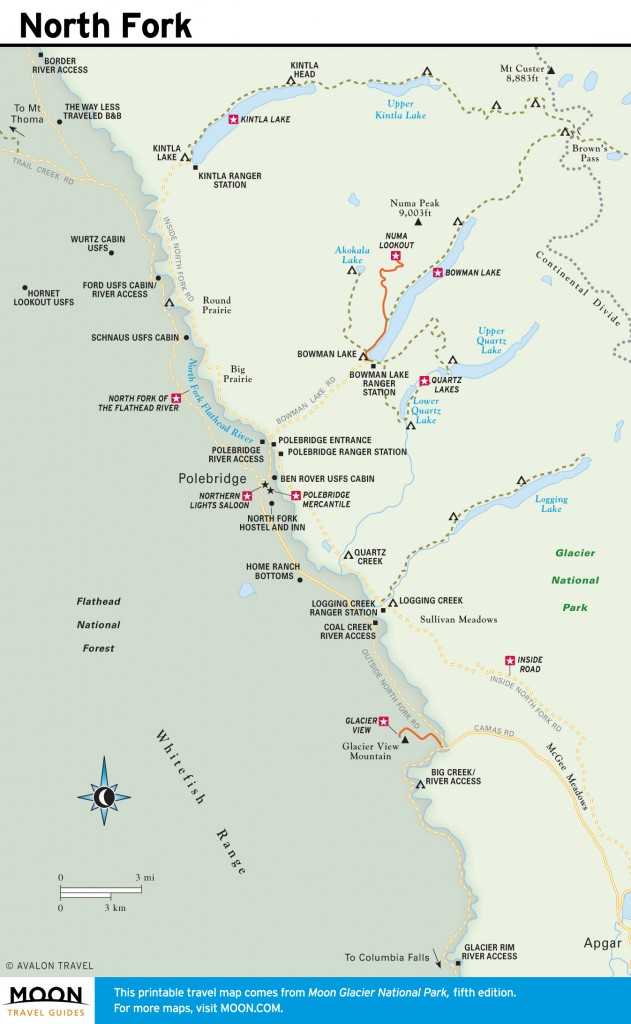

North Fork

Excerpted from the Fifth Edition of Moon Glacier National Park.