The Grand Canyon. Photo © Grand Canyon National Park Service, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

Grand Canyon is a place of grand drama and serene vistas, so vast and varied that each visitor will experience it from a different perspective. Grand Canyon National Park’s mile-deep abyss and 1.2 million acres hold a multitude of experiences, from bustling Grand Canyon Village to wild and lonesome wilderness.Layered cliffs of red, orange, gray, and tan record three eras of geological time, with rocks along the Colorado River that are two billion years old. The canyon itself is five or six million years old and still changing. Wind and moisture sculpt fantastical stone shapes one grain of sand at a time. But nature doesn’t always work slowly—a room-sized platform of limestone at Mather Point once toppled overnight, and a single storm transformed Crystal Rapid from a mellow ride to a maelstrom.

The canyon’s rocky expanse may look stark and forbidding, but it has sheltered people along its river and rim for 10,000 years. The native peoples left signs of their passing in rock art, stone pueblos, and potsherds. Diverse environments, from the North Rim’s boreal forests to the inner canyon’s deserts and river, support more than 2,000 species of plants, mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, including several endangered and threatened species and a few species found nowhere else on the planet.

Hiking and rafting the inner canyon may be challenging, but those who enter Grand Canyon’s heart are rewarded with closer looks at features often hidden within its rocky folds—sinuous side canyons, sparkling waterfalls, and towering monuments of stone. Places like Vishnu Temple and Deer Creek Falls are just small pieces of a whole that is considered one of the world’s seven greatest natural wonders.

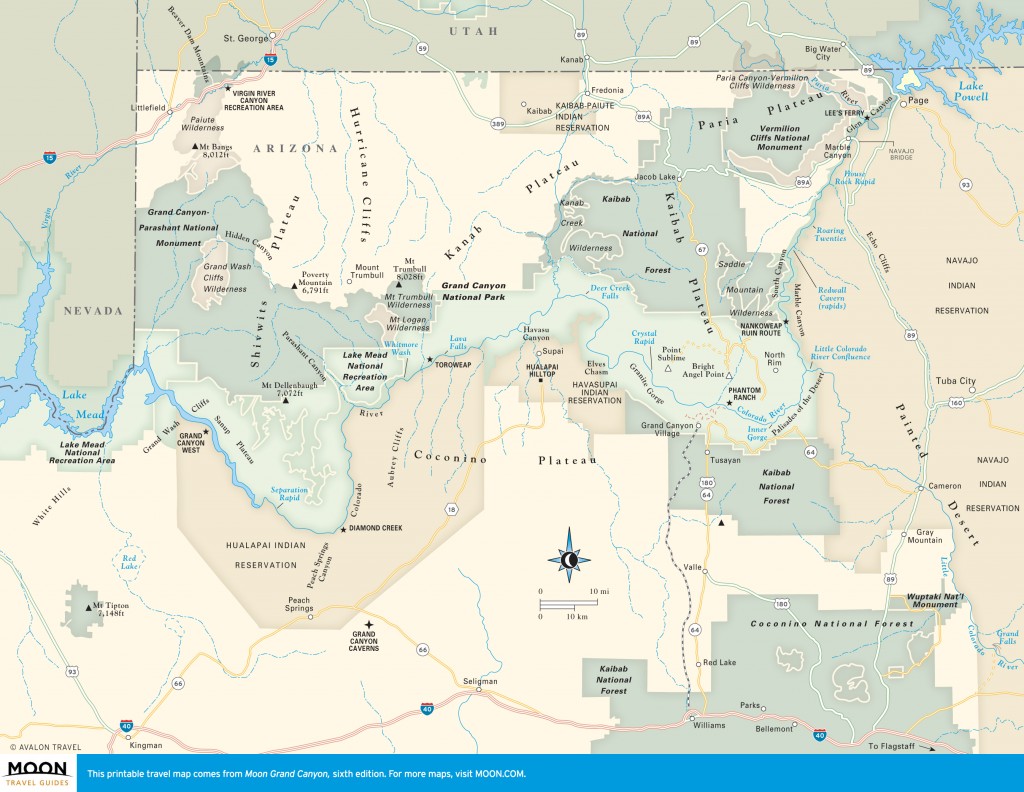

Features outside the park’s boundaries—forests, plateaus, and Indian Reservations—add further perspectives to the canyon experience. You can drive up to the Colorado River at Lees Ferry, mountain bike along the Rainbow Rim, or stroll onto the Hualapai Reservation’s Skywalk, a 70-foot-long glass-bottomed observation deck that stretches into the canyon.

In 1903, Teddy Roosevelt urged every American to see Grand Canyon. Today, some five million visitors each year do, but the Grand Canyon you experience is yours alone.

Excerpted from the Sixth Edition of Moon Grand Canyon.

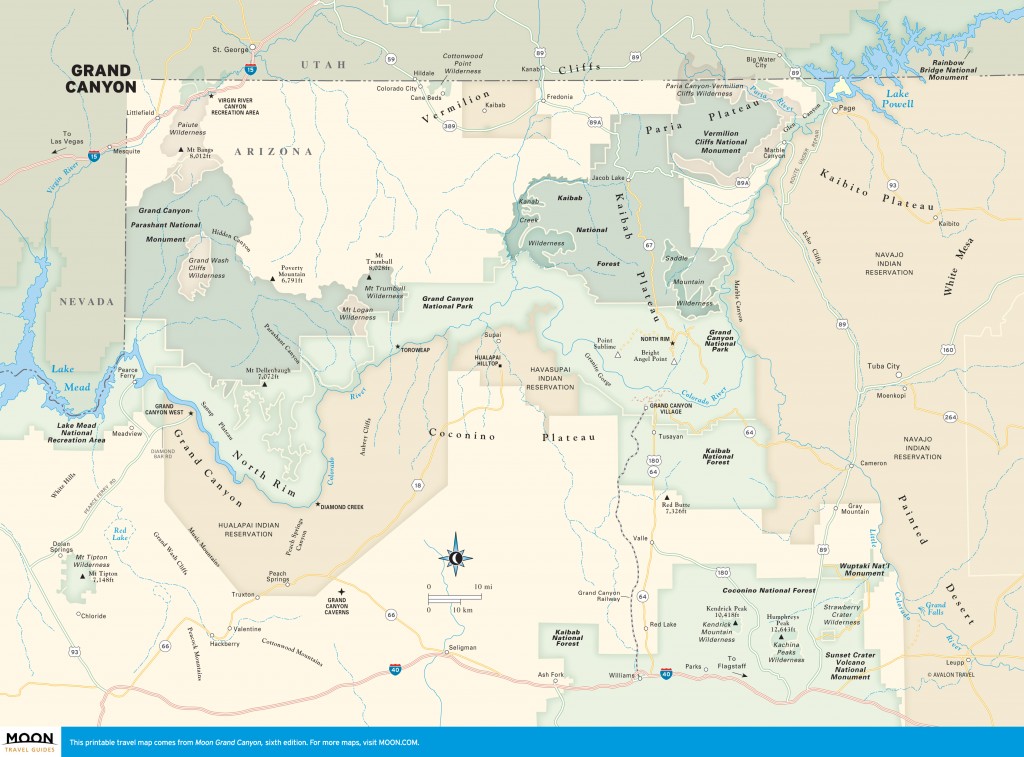

Grand Canyon Overview

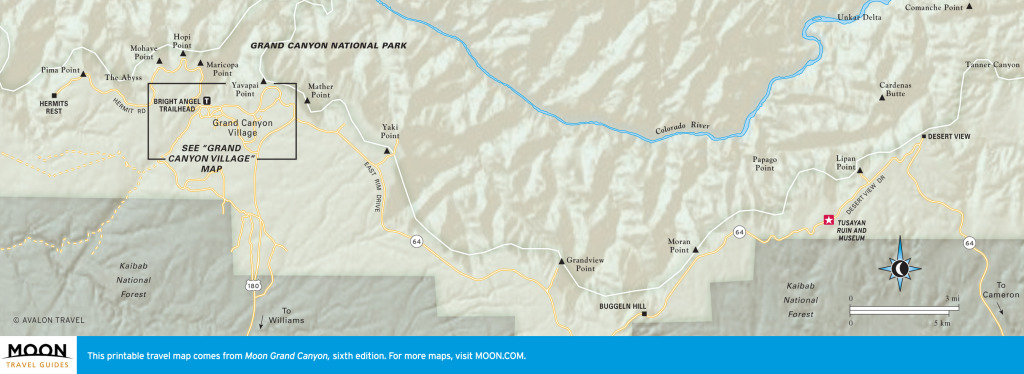

South Rim

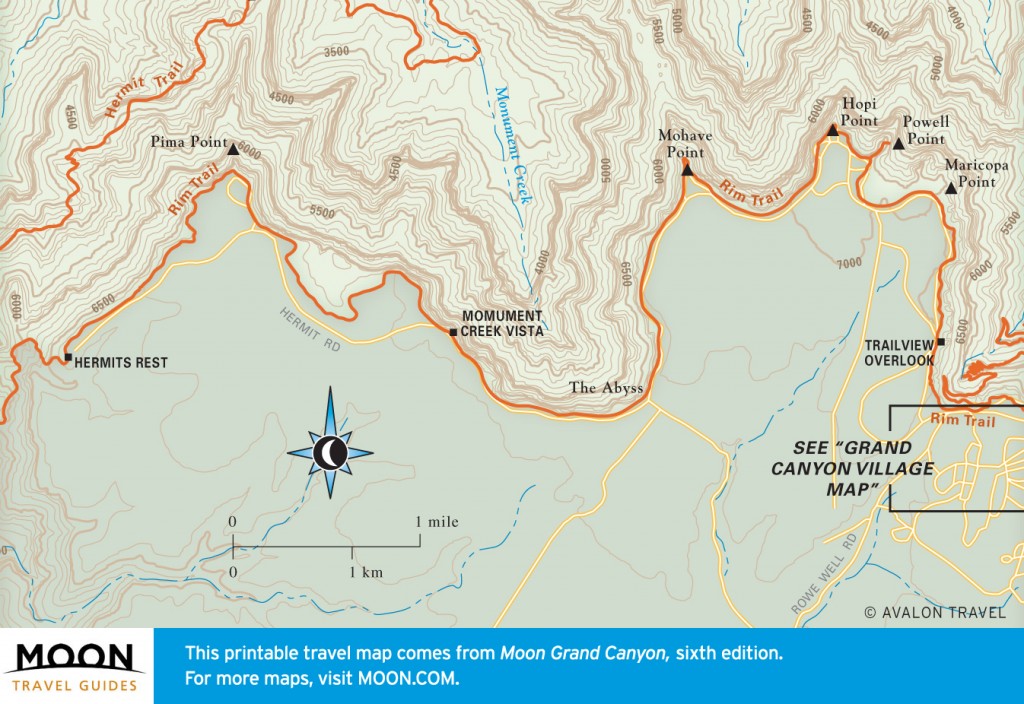

West Rim and Hermit Road

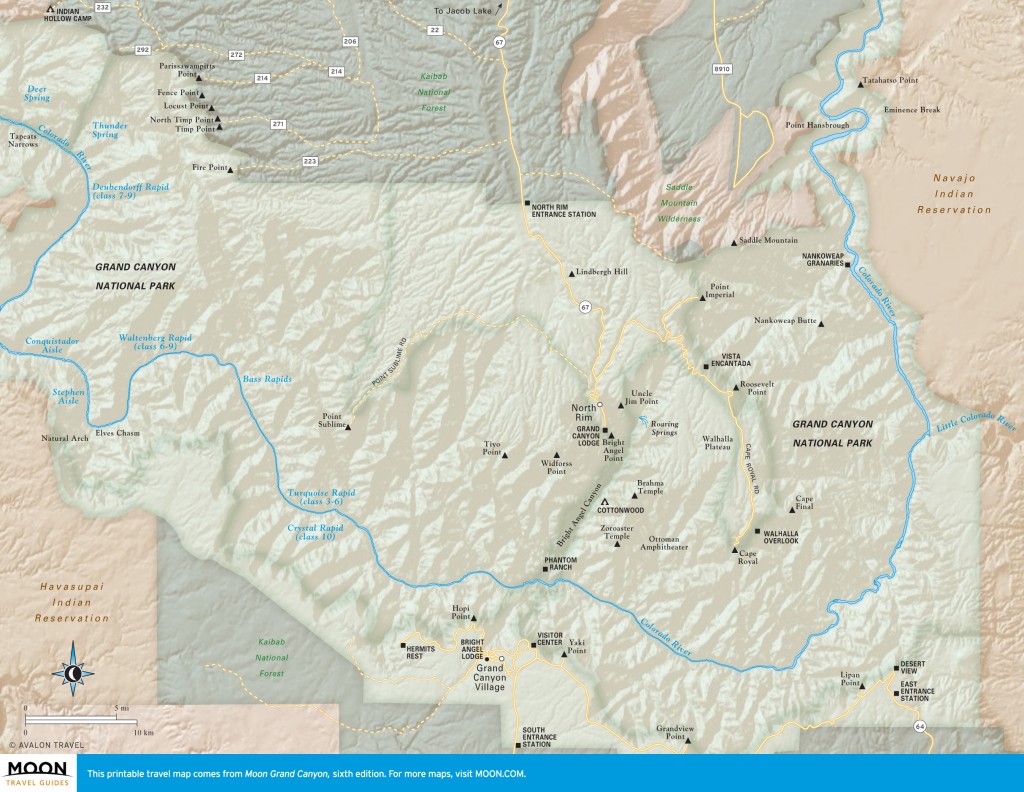

North Rim

The Inner Canyon