A look at the bottling process at World of Coca-Cola in Atlanta, Georgia. Photo © Betsy Weber, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

In the years after the Civil War, Atlanta was a boomtown, with its forward-looking business community using the city’s destruction as a reason to rebuild bigger and better. By 1868, Atlanta was the new capital of Georgia, and a year later a former Confederate officer and druggist from Columbus, Georgia, moved here seeking opportunity. While the company is called Coca-Cola, Atlantans often ask to drink a “Coke-Cola.”John Pemberton was interested in the growing market for health tonics and hit upon a recipe using kola nut and coca leaf extracts. The first version was “French Wine Cola,” but one of Pemberton’s partners came up with “Coca-Cola,” and the world’s premier brand name was born.Twenty years later Asa Griggs Candler bought Pemberton’s company and had two great ideas. First was the idea of selling the product—the ingredients of which were secret, as they are to this day—in syrup form, to be carbonated right at the soda fountain. The second was franchising bottling rights nationwide, which catapulted Coca-Cola to prominence and created a number of family fortunes.

When the Woodruff family acquired Coca-Cola in 1919, president Robert Woodruff set his sights on global expansion. During World War II, in a brilliant blend of patriotism and business savvy, he promised a five-cent bottle to every U.S. serviceman no matter where they were stationed. It was not only a step toward expanding into 200 countries; by gaining the label of “wartime production” Coca-Cola could circumvent the rationing of sugar, its syrup’s main ingredient!

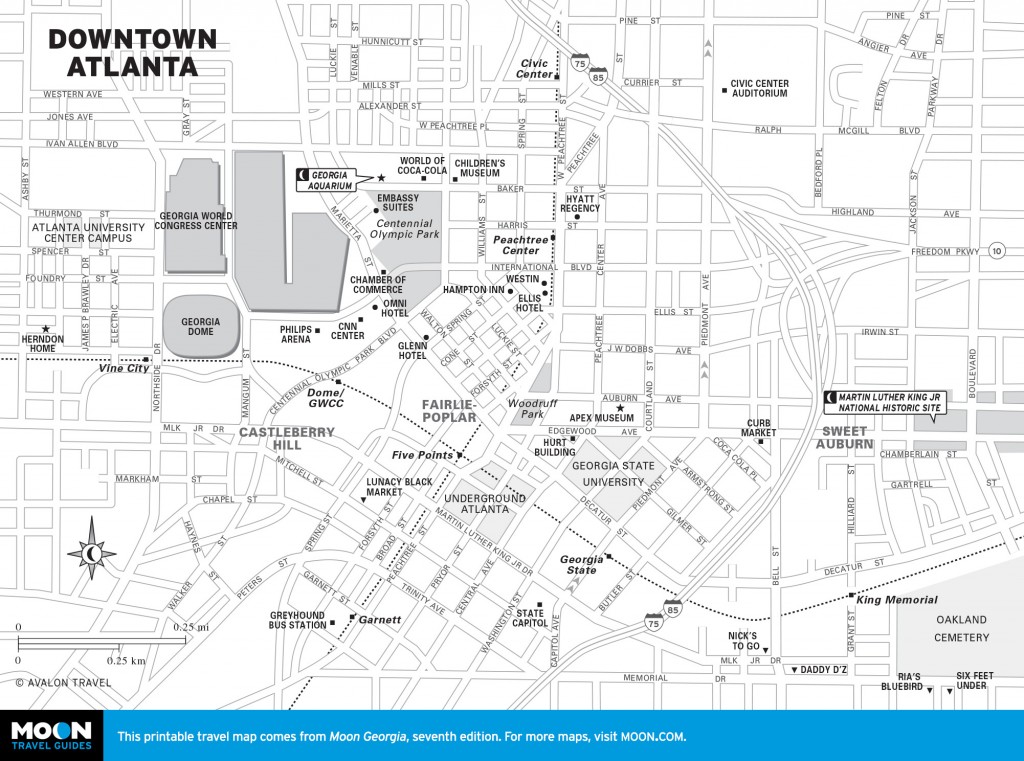

Downtown Atlanta

There’ve been missteps along the way, chiefly the “New Coke” debacle, humorously chronicled at the World of Coca-Cola (121 Baker St. NW, 404/676-5151, daily, hours vary, $16 adults, $12 children), where you can sample a room full of Coke products. The company got in trouble when it was revealed that its Dasani bottled water was just purified City of Atlanta tap water. While the company maintains the product never contained actual cocaine (the drug wasn’t made illegal until 1906), many analysts say it likely contained very minimal traces through the 1920s.

While the company is called Coca-Cola, Atlantans often ask to drink a “Coke-Cola.” Coca-Cola’s philanthropic legacy is felt in Atlanta today at the Robert Woodruff Memorial Arts Center, Emory University, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, among many others. Individually, the late Robert Woodruff’s acts of philanthropy changed the face of the state, but exactly how much we may never know; most of his gifts are reckoned to be anonymous.

Excerpted from the First Edition of Moon Carolinas & Georgia.