The lighthouse at Cape Lookout. Photo © bobistraveling, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

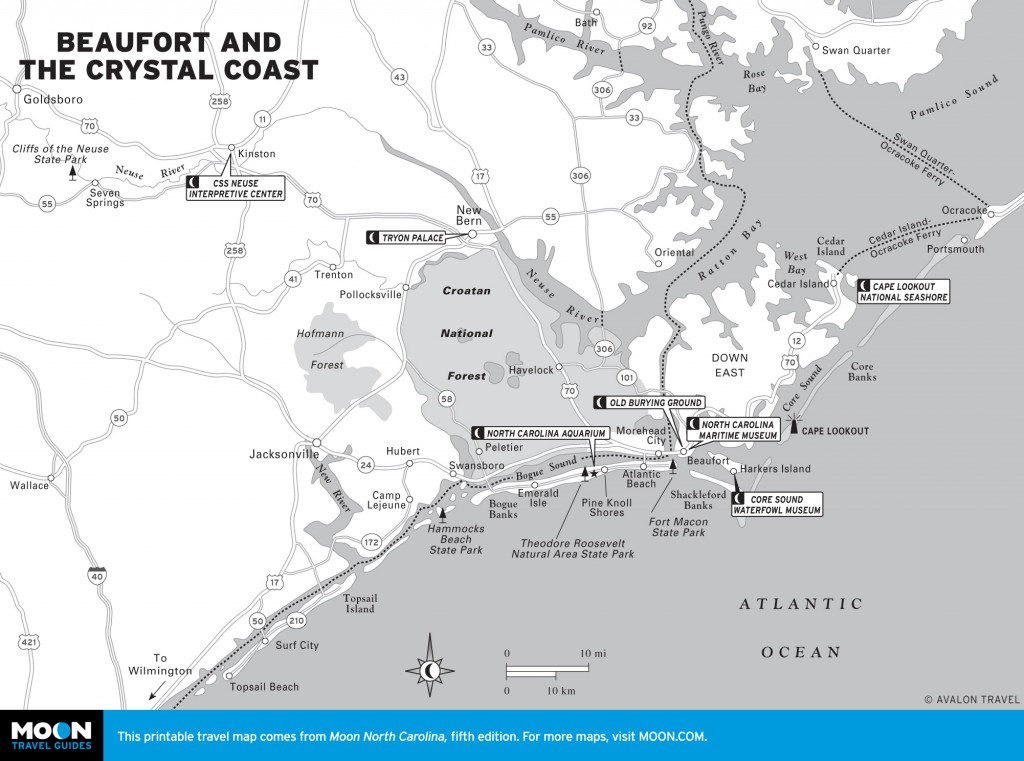

Cape Lookout National Seashore (1800 Islands Rd., Harkers Island, 252/728-2250) is an otherworldly place: 56 miles of beach stretched out across four barrier islands, a long tape of sand seemingly so vulnerable to nature that it’s hard to believe there were ever any towns on its banks. There were: Cape Lookout was settled in the early 1700s, and people in the towns of the south Core Banks made their living in fisheries that might seem brutal to today’s seafood eaters—whaling and catching dolphins and sea turtles, among the more mundane species. Portsmouth, at the north end of the park across the water from Ocracoke, was a busy port of great importance to the early economy of North Carolina. Portsmouth declined slowly, but catastrophe rained down all at once on the people of the southerly Shackleford Banks, who were driven out of their own long-established communities to start new lives on the mainland when a series of terrible hurricanes decimated the islands in the 1890s.Islands often support unique ecosystems. Among the dunes, small patches of maritime forest fight for each drop of fresh water, while ghost forests of trees that were defeated by advancing saltwater look on resignedly. Along the endless beach, loggerhead turtles come ashore to lay their eggs, and in the waters just off the strand, three other species of sea turtles are sometimes seen. Wild horses roam the beaches and dunes, and dolphins frequent both the ocean and sound sides of the islands. Other mammals, though, are all of the small and scrappy variety: raccoons, rodents, otters, and rabbits. Like all of coastal North Carolina, it’s a great place for bird-watching as it’s located in a heavily traveled migratory flyway. Pets are allowed if they’re on a leash. The wild ponies on Shackleford Banks can pose a threat to dogs that get among them, and the dogs can frighten the horses, so be careful not to let them mingle.

For more info, visit the Cape Lookout National Seashore website.×Portsmouth Village, at the northern tip of the Cape Lookout National Seashore, is a peaceful but eerie place. The village looks much as it did 100 years ago, the handsome houses and churches all tidy and in good repair, but with the exception of caretakers and summer volunteers, no one has lived here in nearly 50 years. In 1970 the last two residents moved away from what had once been a town of 700 people and one of the most important shipping ports in North Carolina. Founded before the Revolution, Portsmouth was a lightering station, a port where huge seagoing ships that had traveled across the ocean would stop and have their cargo removed for transport across the shallow sounds in smaller boats. There is a visitors center located at Portsmouth, open varying hours April-October, where you can learn about the village before embarking on a stroll to explore the quiet streets.

In its busy history, Portsmouth was captured by the British during the War of 1812 and by Union troops in the Civil War, underscoring its strategic importance. By the time of the Civil War, though, its utility as a way station was already declining. An 1846 hurricane opened a new inlet at Hatteras, which quickly became a busy shipping channel. After abolition, the town’s lightering trade was no longer profitable without enslaved people to perform much of the labor. The fishing and lifesaving businesses kept the town afloat for a few more generations, but Portsmouth was never the same.

Once a year, an unusual thing happens when boatloads of people arrive on shore, the church bell rings, and the sound of hymns being sung comes through the open church doors. At the Portsmouth Homecoming, descendants of the people who lived here come from all over the state and the rest of the country to pay tribute to their ancestral home. They have an old-time dinner on the grounds and then tour the little village together. It’s like a family reunion with the town itself the matriarch. The rest of the year, Portsmouth receives visitors and National Park Service caretakers, but one senses that it’s already looking forward to the next spring when its children will come home again.

The once-busy villages of Diamond City and Shackleford Banks are like Portsmouth in that, although they have not been occupied for many years, the descendants of the people who lived here retain a profound attachment to their ancestors’ homes. Diamond City and nearby communities met a spectacular end. The hurricane season of 1899 culminated in the San Ciriaco Hurricane, a disastrous storm that destroyed homes and forests, killed livestock, flooded gardens with saltwater, and washed the Shackleford dead out of their graves. The Bankers saw the writing on the wall and moved to the mainland en masse, carrying as much of their property as would fit on boats. Some actually floated their houses across Core Sound. Harkers Island absorbed most of the refugee population, and many also went to Morehead City; their traditions are still an important part of Down East culture. Daily and weekly programs held at the Light Station Pavilion and the porch of the Keepers Quarters during the summer months teach visitors about the natural and human history of Cape Lookout, including what day-to-day life was like for the keeper of the lighthouse and the keeper’s family.

Descendants of the Bankers feel a deep spiritual bond to their ancestors’ home, and for many years they would return frequently, occupying fish camps that they constructed along the beach. When the federal government bought the Banks, it was made known that the fish camps would soon be off-limits to their deedless owners. The outcry and bitterness that ensued reflected the depth of the Core Sounders’ love of their ancestral grounds. The National Park Service may have thought that the fish camps were ephemeral and purely recreational structures, but to the campers, the Banks was still home, even if they had been born on the mainland and had never lived here for longer than a fishing season. Retaining their sense of righteous, if not legal, ownership, many burned down their own fish camps rather than let the government take them down.

By the time you arrive at the 1859 Cape Lookout Lighthouse (252/728-2250, visitors center and Keeper’s Quarters Museum 9am-5pm daily Apr.-Nov., lighthouse climbs 10am-3:45pm Wed.-Sat. early May-mid-Sept., $8 adults, $4 seniors and under age 13), you will have seen it portrayed on dozens of brochures, menus, signs, and souvenirs. With its striking diamond pattern, it looks like a rattlesnake standing at attention. This 163-foot-tall lighthouse was first lit in 1859. Like the other lighthouses along the coast, it’s built of brick. At its base, the walls are nine feet thick, narrowing to two feet at the top. The present lighthouse isn’t the first to guard this section of the coast; originally a lighthouse was built only a few yards away, but it was plagued with problems and replaced by the current structure.

There are cabins to rent on Cape Lookout, but you must reserve well in advance to obtain one. On Long Point, Great Island, and Morris Marina (877/444-6777, Apr.-Nov. $73-170) you can rent cabins with hot and cold water, gas stoves, and furniture, but in some cases visitors must bring their own generators for lighting as well as linens and utensils. Rentals are not available December-March, and before you make a reservation, remember that with no air-conditioning, it can get quite hot in these cabins; fall or spring are more comfortable than summer.

Camping is permitted within Cape Lookout National Seashore. There are no designated campsites or camping amenities, and everything you bring must be carried back out when you leave. Campers can stay for up to 14 days, and large groups (25 or more campers) require special permits. The National Park Service website for Cape Lookout has full details on camping regulations and permits.

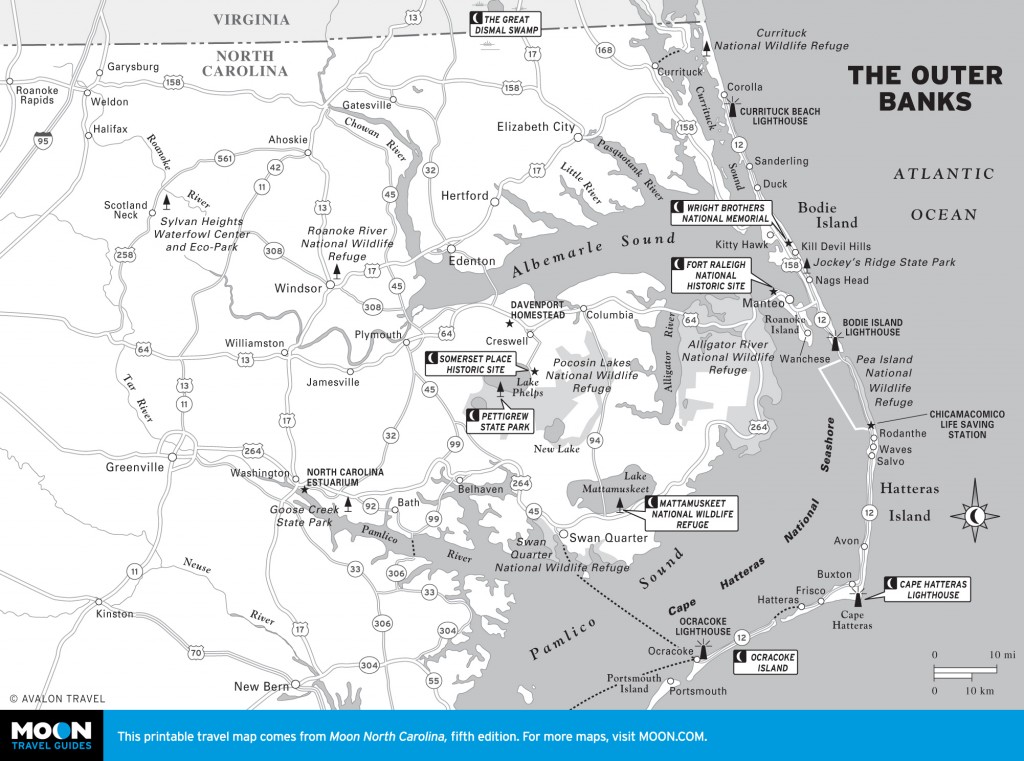

Except for the visitors center at Harkers Island, Cape Lookout National Seashore can only be reached by ferry. Portsmouth, at the northern end of the park, is a short ferry ride from Ocracoke, but Ocracoke is a very long ferry ride from Cedar Island. The Cedar Island-Ocracoke Ferry (800/293-3779) is part of the state ferry system, and costs $15 one-way for regular-size vehicles (pets allowed). It takes 2.25 hours to cross Pamlico Sound, but the ride is fun, and embarking from Cedar Island feels like sailing off the edge of the earth. The Ocracoke-Portsmouth Ferry is a passenger-only commercial route, licensed to Captain Rudy Austin of Austin Boat Tours (252/928- 4361 or 252/928-5431, $20 pp, 3-person minimum, daily as weather permits). Call to ensure a seat. Most ferries operate April-November, with some exceptions.

Commercial ferries cross every day from mainland Carteret County to the southern parts of the national seashore. There is generally a ferry route between Davis and Great Island, but service can be variable; check the Cape Lookout National Seashore website for updates.

From Harkers Island, passenger ferries to Cape Lookout Lighthouse and Shackleford Banks include Harkers Island Fishing Center (252/728-3907, $15 adults, $10 children, $6 pets) and Local Yokel (516 Island Rd., 252/728-2759, $15 adults, $10 children).

From Beaufort, passenger ferries include Outer Banks Ferry Service (326 Front St., 252/728-4129, $15 adults, $8 children), which goes to both Shackleford Banks and to Cape Lookout Lighthouse; Island Ferry Adventures at Barbour’s Marina (610 Front St., 252/728- 6181, $15 adults, $8 children) does as well. Morehead City’s passenger-only Waterfront Ferry Service (201 S. 6th St., 252/503-1955, $15 adults, $8 children) goes to Shackleford Banks too. On-leash pets are generally allowed, but call ahead to confirm with the ferry operator.

Beaufort and the Crystal Coast

The Outer Banks

Excerpted from the Fifth Edition of Moon North Carolina.