Cyclists rest under a tree in beautiful Stanley Park. Photo © Matt Trapp/123rf.

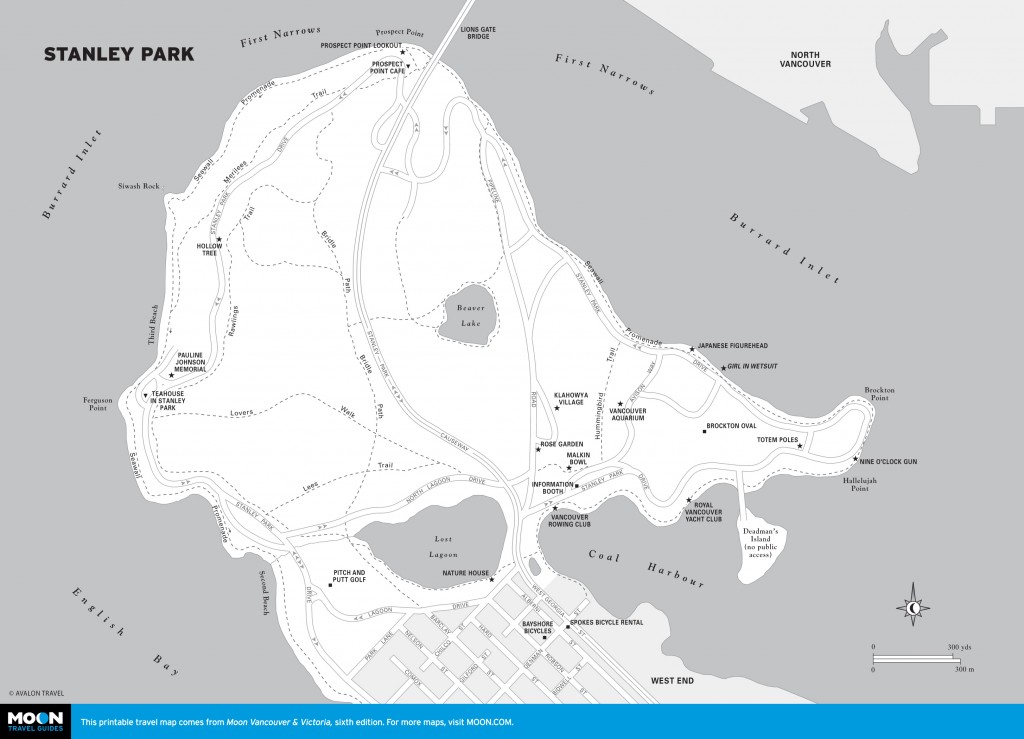

Beautiful Stanley Park, a lush 405-hectare (1,000-acre) tree- and garden-carpeted peninsula jutting out into Burrard Inlet, is a sight for sore eyes in any weather—an enormous peaceful oasis sandwiched between the city center’s skyscrapers and the North Shore at the other end of Lions Gate Bridge. Unlike other famous parks, like New York’s Central Park and London’s Royal Park, Stanley Park is a permanent preserve of wilderness in the heart of the city, complete with dense coastal forests and abundant wildlife. It was Alexander Hamilton, land commissioner for the Canadian Pacific Railroad (CPR), whose proposal to preserve the end of Burrard Peninsula led to the creation of the park.It was Alexander Hamilton, land commissioner for the Canadian Pacific Railroad (CPR), whose proposal to preserve the end of Burrard Peninsula led to the creation of the park. Later named for Lord Stanley, Canada’s governor-general from 1888 to 1893, the park was dedicated for “the use and enjoyment of all peoples of all colors, creeds, and customs for all time.” Stanley Park’s creation demonstrated incredible foresight on the part of Hamilton and city leaders, considering that at the time most of the West End was wilderness and the vote took place on June 23, 1886—just 12 days after the entire city had burned to the ground. The biggest changes to the park in the ensuing years have been the work of Mother Nature, including a devastating windstorm in December 2006 that destroyed hundreds of trees.Walk or cycle the 10-kilometer (6.2-mile) Seawall Promenade or drive the perimeter via Stanley Park Drive to take in beautiful water and city views. Travel along both is one-way in a counterclockwise direction (those on foot can go either way, but if you travel clockwise you’ll be going against the flow). For vehicle traffic, the main entrance to Stanley Park is at the beginning of Stanley Park Drive, which veers right from the end of Georgia Street; on foot, follow Denman Street to its north end and you’ll find a pathway leading around Coal Harbour into the park. Either way, you’ll pass a small information booth where park maps are available. Just before the booth, take Pipeline Road to access Malkin Bowl, home to outdoor theater productions; a rose garden; and forest-encircled Beaver Lake. North on Pipeline Road from the main entrance is miniature railway (604/257-8530), with carriages pulled by replicas of historical Canadian Pacific locomotives. Pipeline Road rejoins Stanley Park Drive near the Lions Gate Bridge, but by not returning to the park entrance you’ll miss most of the following sights.

Stanley Park

Behind the information booth is Klahowya Village (Pipeline Rd., 604/921-1070, 11am-4pm Mon.-Thurs., 11am-5pm Fri.-Sun. mid- June to Aug., free), the best place in the city to learn about local aboriginal culture. It offers a full schedule of performances, art and craft workshops, and an excellent gift shop of traditional works. The highlight is a miniature train ride through the surrounding forest, which is accompanied by aboriginal dancers.

A short walk through the forest from Klahowya Village is Vancouver Aquarium (Avison Way., 604/659-3474, 9:30am-7pm daily in summer, 10am-5pm daily the rest of the year, adult $32, senior and student $26, child $21), Canada’s largest and the third largest in North America. Guarding the entrance is a 5-meter (16-foot) killer whale sculpture by preeminent native artist Bill Reid. More than 8,000 aquatic animals and 600 species are on display, representing all corners of the planet, from the oceans of the Arctic to the rainforests of the Amazon.

The Wild Coast exhibit features local marine mammals, including sea lions, dolphins, and seals. Several other exhibits highlight regional marinelife, including Pacific Canada, the first display you’ll come to through the aquarium entrance. Pacific Canada is of particular interest because it contains a wide variety of sealife from the Gulf of Georgia, including the giant fish of the deep, halibut, and playful sea otters that frolic in the kelp. In the Amazon Gallery, experience a computer-generated hourly tropical rainstorm and see numerous fascinating creatures, such as crocodiles and piranhas, as well as bizarre misfits like the four-eyed fish. The Tropic Zone re-creates an Indonesian marine park, complete with colorful sealife, coral, and small reef sharks. At the far end of the aquarium, a large pool holding beluga whales—distinctive pure white marine mammals—and sea lions, which can be viewed from above- or below ground, represents Canada’s Arctic. A part of the complex is also devoted to the rehabilitation of injured marine mammals; Clownfish Cove is set aside especially for younger visitors; and there’s a packed interpretive program of talks and tours, including a 90-minute behind-the-scenes beluga tour for $130 per person.

The following sights are listed from the information booth, which overlooks Coal Harbour, in a counterclockwise direction. From this point, Stanley Park Drive and the Seawall Promenade pass the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club and Deadman’s Island. Now a naval reserve, the island has a dark history, having witnessed many battles between native tribes, been the burial place of the last of the Coast Salish people, and been used as a quarantine station during an early smallpox epidemic. Off the island is a floating gas station, used by watercraft and floatplanes.

The first worthwhile stop at Brockton Point (which refers to the entire eastern tip of the park) is a collection of authentic totem poles from the Kwagiulth people, who lived along the coast north of present-day Vancouver. Before rounding the actual point, you’ll pass the Nine o’Clock Gun, which is fired each evening at, you guessed it, 9pm. Its original purpose was to allow ship captains to set their chronometers to the exact time. Much of the Brockton Point peninsula is dedicated to sporting fields, and on any sunny afternoon young Vancouverites can be seen playing traditional British pursuits, such as rugby and cricket. Around the point, the road and the seawall continue to hug the shoreline, passing the famous Girl in Wetsuit bronze sculpture and a figurehead commemorating Vancouver’s links to Japan. Then the two paths divide. The seawall passes directly under the Lions Gate Bridge, which made the North Shore accessible to development after its 1938 opening. Meanwhile, the vehicular road loops back to a higher elevation to Prospect Point Lookout, a memorial to the SS Beaver (which was the first HBC steamship to travel along this stretch of the coast), and a café (a stairway leads up from the seawall to the café).

The Lions Gate Bridge marks the halfway point of the seawall as well as a change in scenery. From this point to Second Beach, the views are westward toward the Strait of Georgia and across English Bay to Central Vancouver. The next stretch of pleasant pathway, about 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) long, is sandwiched between the water and steep cliffs, with Siwash Rock being the only distinctive landmark. This volcanic outcrop sits just offshore, rising more than 15 meters (50 feet) from the lapping waters of English Bay. If you’re traveling along Stanley Park Drive, park at the Hollow Tree and walk back up the hill to a lookout high above the rock.

Continuing south, the seawall and Stanley Park Drive converge at the south end of Third Beach, a popular swimming and sunbathing spot (and a great place to watch the setting sun). The beach’s southern end is guarded by Ferguson Point, where a fountain marks the final resting spot of renowned native poet Pauline Johnson. Second Beach is 1 kilometer (0.6 mile) farther back toward the city, where you’ll find an outdoor swimming pool, a pitch-and-putt golf course, a putting green, tennis courts, and lawn bowling greens. On summer evenings an area behind the beach is set aside for local dance clubs to practice their skills. From Second Beach it’s only a short distance to busy Denman Street and English Bay Beach, or you can cut across the park back to Coal Harbour.

At the time of European settlement, Coal Harbour extended almost all the way across the peninsula to Second Beach. With the receding of the tides, the water would drain out from the head of the inlet, creating a massive tidal flat and inspiring native-born Pauline Johnson to pen the poem “Lost Lagoon,” a name that holds to this day. A bridge across the harbor was replaced with a causeway in 1922, blocking the flow of the tide and creating a real lagoon. Over the years it has become home to large populations of waterfowl, including great blue herons, trumpeter swans, grebes, and a variety of ducks. It is also a rest stop for migrating Canada geese each spring and fall. In the center of the lake, Jubilee Fountain (erected to celebrate the park’s 50th anniversary in 1936) is illuminated each night. A 1.6-kilometer (1-mile) walking trail encircles the lagoon, passing the Nature House (604/257-8544, 10am- 5pm Tues.-Sun. July-Aug., 10am-4pm Sat.- Sun. Sept.-June, free) at the southeast corner, which holds natural history displays and general park information.

Excerpted from the Sixth Edition of Moon Vancouver & Victoria.