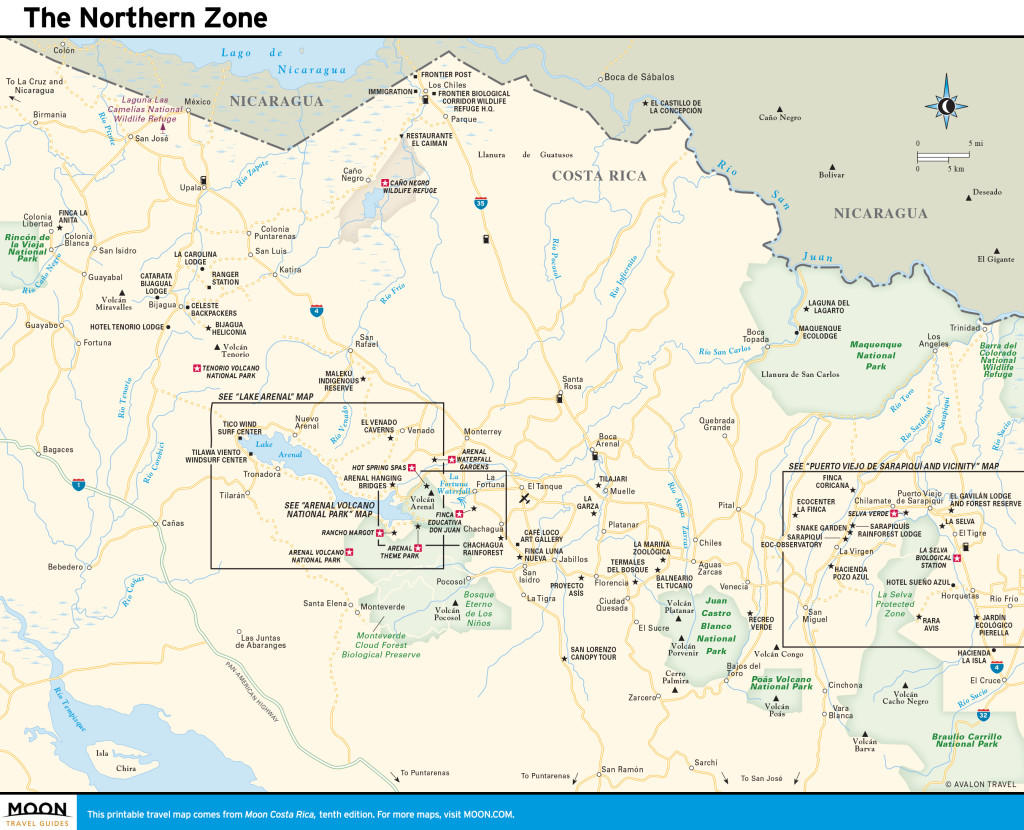

Costa Rica’s northern lowlands constitute a 40,000-square-kilometer (15,400-square-mile) watershed drained by the Ríos Frío, San Carlos, and Sarapiquí and their tributaries, which flow north to the Río San Juan, forming the border with Nicaragua. The rivers meander like restless snakes and flood in the wet season, when much of the landscape is transformed into swampy marshlands. The region is made up of two separate plains (llanuras): in the west, the Llanura de los Guatusos, and farther east, the Llanura de San Carlos. Today, travelers are flocking here thanks to the singular popularity of Volcán Arenal and the fistful of adventures based around nearby La Fortuna.

Arenal Volcano. Photo © Christopher P. Baker.

Today, travelers are flocking here thanks to the singular popularity of Volcán Arenal and the fistful of adventures based around nearby La Fortuna.These plains were once rampant with tropical rainforest. During recent decades much of it has been felled as the lowlands have been transformed into farmland. But there’s still plenty of rainforest extending for miles across the plains and clambering up the north-facing slopes of the cordilleras, whose scarp face hems the lowlands.Today, the region is a breadbasket for the nation, and most of the working population is employed in agriculture. The land in the southern uplands area of San Carlos, centered on the regional capital of Ciudad Quesada, is almost 70 percent dedicated to dairy cattle. The lowlands are the realm of beef cattle and plantations of pineapples, bananas, and citrus.

The climate has much in common with the Caribbean coast: warm, humid, and consistently wet. Temperatures hover at 25-27°C (77-81°F) year-round. The climatic periods are not as well defined as those of other parts of the nation, and rarely does a week pass without a prolonged and heavy rain shower (it rains a little less from February to the beginning of May). Precipitation tends to diminish and the dry season grows more pronounced northward and westward.

The Northern Zone

Allocate up to one week if you want to fully explore the lowlands. The region is a vast triangle, broad to the east and narrowing to the west. Much of the region is accessible only along rough dirt roads that turn to muddy quagmires in the wet season; a 4WD vehicle is essential. You can descend from the Central Highlands via any of half a dozen routes that drop sharply down the steep north-facing slopes of the cordilleras and onto the plains. Choose your route according to your desired destination.

Main street in La Fortuna with Arenal Volcano in the distance. Photo © Christopher P. Baker.

Most sights of interest concentrate near the towns of La Fortuna and Puerto Viejo de Sarapiquí. For the naturalist, there are opportunities galore for bird-watching and wildlife-viewing, particularly around Puerto Viejo de Sarapiquí, where the lower slopes of Parque Nacional Braulio Carrillo provide easy immersion in rainforest from nature lodges such as Selva Verde and La Selva. Boat trips along the Río Sarapiquí are also recommended for spotting wildlife.

The main tourist center is La Fortuna, which has dozens of accommodations and restaurants, plus tour companies offering horseback riding, river trips, bicycle rides, and other adventure excursions. Its location at the foot of Parque Nacional Volcán Arenal makes it a great base for exploring; three days here is about right. The longer you linger, the greater your chance of seeing an eruption, although since 2010 the volcano has been relatively quiescent. Volcán Arenal looms over Laguna de Arenal, whose magnificent alpine setting makes for an outstanding drive.

To the far west, the slopes of the Tenorio and Miravalles volcanoes are less developed but worthwhile, with several new nature lodges around Bijagua, one of my favorite regions. To the north, the town of Los Chiles is a gateway to Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre Caño Negro, a wildlife refuge that is one of the nation’s prime bird-watching and fishing sites.

Excerpted from the Tenth Edition of Moon Costa Rica.