The beach at Monterrico during a Leatherback hatchling release. Photo © Marina Kuperman Villatoro, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

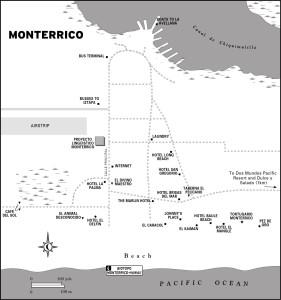

Monterrico

This protected biotope encompasses the beaches and mangrove swamps of Monterrico and those of adjacent Hawaii, which are the prime nesting sites for sea turtles on Guatemala’s Pacific seaboard, including the giant leatherback and smaller olive ridley turtles. Locals are involved in a conservation project with the local turtle hatchery whereby they are allowed to keep half of the eggs they collect from nests and turn in the other half to the hatchery. Sadly, leatherback turtle arrivals have declined dramatically in recent years.In the heart of town and run by the San Carlos University Center for Conservation Studies (CECON), the Tortugario Monterrico (on the sandy street just behind Johnny’s Place, 8 a.m.-noon and 2-5 p.m. daily, $1) encompasses a turtle hatchery right on the beach, where collected eggs are reburied and allowed to hatch under protected conditions. There’s also a visitors center. In addition to baby sea turtles, the hatchery has enclosures housing green iguanas, crocodiles, and freshwater turtles bred on-site for release into the wild. The staff at CECON is always on the lookout for Spanish-speaking volunteers.

If you’re traveling to the Monterrico-Hawaii area between June and December, you might have the opportunity to witness a sea turtle coming ashore to lay its eggs or watch baby sea turtles making their maiden voyage out to sea. Turtle nesting peaks during August and September, when you might be able to glimpse a large leatherback (baule) or the smaller olive ridley (parlama) coming ashore to lay eggs. Unfortunately, locals are also on the lookout for egg-laying sea turtles to snatch up the eggs and sell them, but under an agreement with the CECON monitoring station at Monterrico and ARCAS in Hawaii, they donate part of their stash toward conservation efforts. Your best bet for seeing a nesting turtle is to go with one of the CECON-trained guides or volunteer with ARCAS.

Volunteers are welcome at both stations. Among the duties are the collection of turtle eggs after the mothers have come ashore and moving them to a protected nesting site, where they are reburied and allowed to hatch. Typical incubation periods for olive ridley eggs is 50 days, 72 for leatherbacks. After a few days in a holding pen, the young turtles are released, either at sunrise or sunset, and make their way across the sand and into the ocean. As the young turtles scamper across the sand, they are being imprinted with the unique details of the beach and its sand, where they will return and nest when they are adults. All this assumes they make it to adulthood, a big assumption when taking into account that only one turtle in 100 makes it to adulthood. Sea turtles are threatened not just by the collection of their eggs but also by fishing activities, where they often end up in nets, and sea pollution. Plastic bags, for example, are often mistaken for jellyfish by hungry sea turtles. The CECON station at Monterrico releases about 5,000 sea turtle hatchlings per year. Turtle races, involving the release of new hatchlings on their maiden voyage to the sea, are no longer held because they were disruptive to the baby turtles’ development and shortcircuited the very conservation efforts they were meant to support. A newer initiative is the annual Festival de la Tortuga Marina, which takes place sometime during October or November. It features turtle releases, live music, and a surfing competition.

The ARC AS turtle hatchery in Hawaii also releases sea turtles. Visitors are allowed to witness turtle releases in limited numbers for a donation of about $3.25 (includes admission to the hatchery). If you’re interested in volunteering with sea turtle conservation efforts, check out local grassroots turtle conservation group Akazul.

Excerpted from the Fourth Edition of Moon Guatemala.