Stone carvings at the Ruins of Copán. Photo © Vojtech Vlk/123rf.

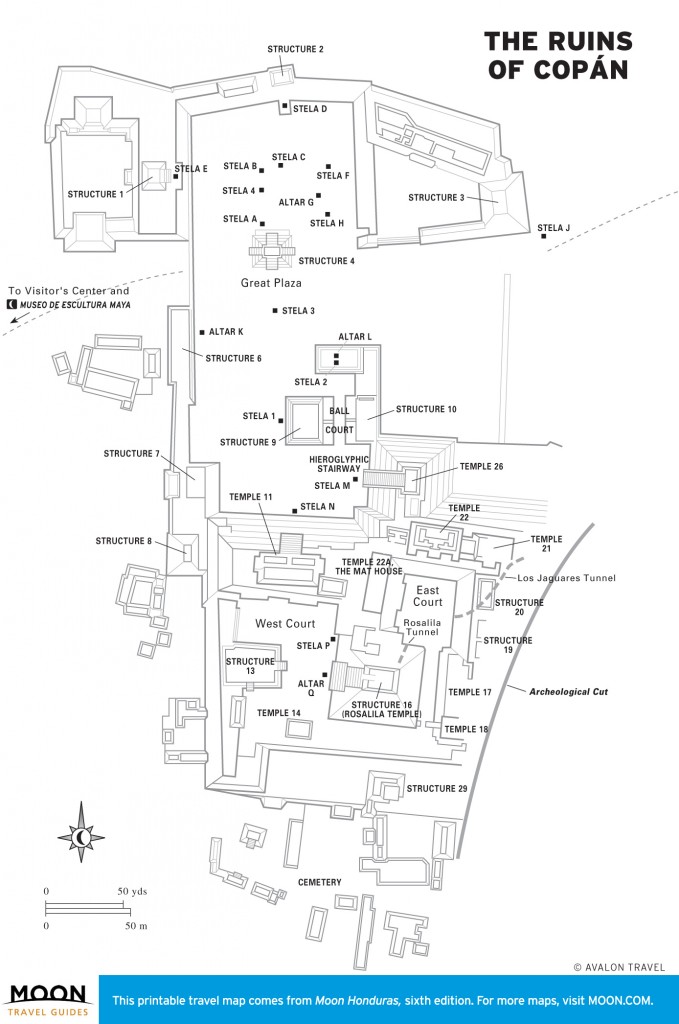

The ruins of Copán are about a kilometer east of Copán Ruinas on the road toward San Pedro Sula, set off the road in a six-hectare wooded archaeological park along the edge of the Río Copán. After buying your US$15 entrance ticket, walk up the path from the visitors center through tall trees to the entrance gate, where a guard will take your ticket. If you’d like to enter the archaeological tunnels, buy an additional ticket for US$15 (a high price for the experience, recommended for archaeology buffs only). (Tickets for the adjacent Museo de Escultura Maya are also sold at the visitors center, US$7 and highly recommended.)Much of the original sculpture work at Copán has been removed from the grounds and replaced by exact duplicates. Although this is a bit disappointing for visitors, it is essential if the city’s artistic legacy is not to be lost forever, worn away by the elements and thousands of curious hands. Most of the finest stelae and carvings can now be seen in the Museo de Escultura Maya.

Just before the place where the guards check your ticket is a kilometer-long nature trail with examples of ceiba, strangler fig, and other plants characteristic of the jungle that originally covered the Valle de Copán, worth taking a brief stroll along either before or after visiting the ruins.

Past the gate, where colorful macaws hang out, the trail heading to the right brings visitors to the Acropolis, a massive architectural complex built over the course of the city’s history and considered to be the central axis point of Copán, around which the rest of the city was focused. At the highest points, the structures stretch 30 meters above the Great Plaza (thus it was dubbed the Acropolis, or “high city,” by archaeologists), and the many large trees still standing atop the huge structure only add to its imposing grandeur. The current Acropolis—perhaps only two-thirds as big as it was during the city’s heyday—is formed by at least two million cubic meters of fill. Some of the most fascinating archaeological finds in recent years have come from digging under buildings in the Acropolis and finding earlier temples, which were carefully buried and built over.

A steep set of stairs leads up to the West Court, a small grassy plaza surrounded by temples to the underworld. The first stela you reach, Stela P, is said to be the oldest of Copán (although the one here is a replica; you’ll have to visit the Museo de Escultura Maya to see the original). The figure in the stela is Humo Serpiente, or Smoke Snake (Butz´ Chan in Maya), the 11th ruler of Copán, with gods above him. At the base of Structure 16 on the edge of the West Court is a square sculpture known as Altar Q. Possibly the single most fascinating piece of art at Copán, it depicts 16 seated men, carved around the four sides of a square stone altar. For many years, following the theory of archaeologist Herbert Joseph Spinden, it was believed the altar illustrated a gathering of Mayan astronomers in the 6th century. However, following breakthroughs in deciphering Mayan hieroglyphics, archaeologists now know the altar is a history of the city’s rulers. The 16 men are, in fact, all the rulers of the Copán dynasty, with the first ruler, Yax K’uk’Mo’, shown passing the ruling baton—and the symbolic right to rule—on to the last, Yax Pac, who ordered the altar built in 776.

Between the West Court and the nearby East Court is Structure 16, a temple dedicated to war, death, and the veneration of past rulers.

Heading around Structure 16 toward the East Court, one can look out to the right over the Cemetery, so called for the many bones found during excavations. Archaeologists later came to realize that the area was residential, where the royal elite lived. Homes were clustered around courtyards, and as per tradition, the deceased were buried next to their homes.

The East Court was Copán’s original plaza. It is also known as the Plaza de Jaguares, for the two sculptures of dancing jaguars on the western side of the plaza, flanking a carving of K’inich Ahau, the sun god. Deep underneath the floor of the plaza, found by archaeologists in 1992 and 1993, are the tombs of Copán’s founder, Yax K’uk’ Mo’, and his wife, who were both venerated by later generations as semidivine. The tombs were built at a time when none of the rest of the Acropolis existed, and are thought to have formed the axis for the rest of Copán’s growth. Studies are still underway on the tomb discoveries, which for the moment remain out of public view.

Underneath Structure 16, in 1989, Honduran archaeologist Ricardo Agurcia found the most complete temple ever uncovered at Copán. It’s called Rosalila (“rose-lilac”) for its original paint, which can still be seen. Rosalila is considered the best-preserved temple anywhere in the Mayan zone. The temple was erected by Copán’s 10th ruler, Moon Jaguar, in 571. The short tunnel accessing the front of Rosalila is open to the public for a US$15 fee, paid at the museum entrance. A full-scale replica of Rosalila is in the Museo de Escultura Maya, which gives a much better sense of the grandeur of the temple than what can be glimpsed through the two small windows in the tunnel.

The ticket price of the tunnel allows visitors to go inside a second, longer tunnel, which begins in the East Court and goes underneath Structure 20 to come out on the far northeast corner of the Acropolis. This tunnel has many more windows, which reveal sculptures of the temple beneath the temple. Both tunnels are well lit and have written descriptions in English and Spanish explaining aspects of Copán archaeology.

On the eastern side of the East Court, the Acropolis drops off in an abrupt cliff down to where the Río Copán ran for a time, before it was diverted to its current course in 1935. Since the river ran alongside the Acropolis, it ate away at the structure, leaving a cross section termed by Mayanist Sylvanus Morley, “the world’s greatest archaeological cut.”

Climbing up the northern side of the East Court brings visitors to Temple 22, a “Sacred Mountain,” the site of important rituals and sacrifices in which the ruler participated. The skull-like stone carving on the side of the structure is of a macaw, the God of Brilliance.

Next to Temple 22 is a small, not visually arresting building called the Mat House, occupying a corner of the Acropolis near the top of the Hieroglyphic Stairway. It was erected in 746 by Smoke Monkey, not long after the shocking capture and decapitation of his predecessor, 18 Rabbit. Decorated with carvings of mats all around its walls, the Mat House was evidently some sort of communal government house; the mat has always symbolized a community council in Mayan tradition. Following 18 Rabbit’s death, the Copán dynasty weakened so much that Smoke Monkey was forced to govern with a council of lords, who were commemorated on the building according to their neighborhood. The dancing jaguar carved onto the steps leading up to the Mat House is of Smoke Jaguar.

As you cross the small open area toward Temple 11, stop for the photo op looking out over the Ball Court. At Temple 11, take a look near the ground on the western side for the famous sculpture, “Old Man’s Head.” It is believed that there were originally four larger-than-life sculptures, to represent the “Pawahtuns,” deities that the Maya believed to be the pillars that held up the four corners of the earth.

Temple 11 was built by Yax Pac, the last great king of Copán, and completed in a.d. 769. Experts believe that it symbolized a portal to the Otherworld, a foreshadowing of Copán’s impending downfall.

After sneaking a peek of the Great Plaza through the trees, visitors head down a stairway that brings them to the extraordinary Hieroglyphic Stairway, the longest hieroglyphic inscription found anywhere in the Americas. It rises from the southeast corner of the plaza up the side of the Acropolis, and is now unfortunately covered with a roof to protect it from the elements. According to recent studies, the 72 steps contain more than 1,093 glyphs (which is far less than the 2,500 previously thought, but still a heck of a lot). It was built in 753 by Smoke Shell to recount the history of Copán’s previous rulers. Since the city was declining in prestige at that point, the stairway was shoddily made compared to other structures, and it collapsed at some point before archaeologists began working at the ruins. In the 1940s, the stairs were assembled in the current, random order. It is thought that about 15 of the stairs, mainly on the lower section, are in their correct position. A group of archaeologists have been using computer analysis of photographs to try to re-create the correct order of the stairway and thus read the long inscription left to us by Smoke Shell 1,250 years ago.

Underneath the Hieroglyphic Stairway, a tomb was discovered in 1989. Laden with painted pottery and jade sculptures, it is thought to have held a scribe, possibly one of the sons of Smoke Imix. In 1993, farther down below the stairway, archaeologists found a subtemple they dubbed Papagayo, erected by the second ruler of Copán, Mat Head. Deeper still, under Papagayo, a room was unearthed dedicated to the founder of Copán’s ruling dynasty, Yax K’uk’ Mo’, dubbed the Founder’s Room. Archaeologists believe the room was used as a place of reverence for Yax K’uk’ Mo’ for more than 300 years, possibly frequented by players from the adjacent ball court before or after their pelota matches.

Just north of the Hieroglyphic Stairway is the Ball Court, perhaps the best-recognized and most-often-photographed piece of architecture at Copán. (You may recognize it from the image on the one-lempira note in your wallet.) It is the third and final ball court erected on the site and was completed in 738. No exact information is available on how the game was played, but it is thought players bounced a hard rubber ball off the slanted walls of the court, keeping it in the air without using their hands. (A video, made by National Geographic of a re-creation of the ball game filmed in Mexico, is on continuous loop at the Casa K’inich.) Only the nobility of Copán were allowed to play (or watch), and it is said that if the game was political, the loser died, while if the game was religious, the winner died. Atop the slanted walls are three intricate macaw heads on each side—if the ball touched the ear of the macaw, the team earned a point—as well as small compartments, which the players may have used as dressing rooms.

The Ball Court leads out to the Great Plaza. In this expansive grassy area, which was graded and paved with white stucco during the heyday of the city, are many of Copán’s most famous stelae—freestanding sculptures carved on all four sides with pictures of past rulers, gods, and hieroglyphics. Red paint, traces of which can be seen on Stela C, built in 730, is thought to have once covered all the stelae. The paint is a mix of mercury sulfate and resins from certain trees found in the valley. Most of the stelae in the Great Plaza were erected during the reign of Smoke Imix (628–695) and 18 Rabbit (695–738), at the zenith of the city’s power and wealth.

All of the stelae are fascinating works of art, but one of particular interest is Stela H (built in 730), which appears to depict a woman wearing jewelry and a leopard skin under her dress. She may have been 18 Rabbit’s wife.

Also worth noting is the round stone next to Stela 4, with a bowl-shaped indent carved into the top, from which curving indentations swirl down the sides. It is believed that human sacrifices were made upon this rock, the blood caught in the bowl-shaped indent, then running down the sides of the stone along the curved indentations, where it was either collected or spilled on the ground.

A wide path leads out of the plaza through a forested area, with many uncovered mounds among the trees—some 4,000 of them, according to one of the guides at the ruins—returning visitors to the entrance gate.

Two kilometers up the highway toward San Pedro Sula from the main ruins is the residential area of Las Sepulturas. Ignored by early archaeologists, Las Sepulturas has, in recent years, provided valuable information about the day-to-day lives of Copán’s ruling elite. The area received its macabre name (“The Tombs”) from local campesinos, who farmed in the area and, in the course of their work, uncovered many tombs of nobles who were buried next to their houses, as was the Mayan custom.

Although these ruins are not as visually interesting to the casual tourist as the principal group, they are well worth a visit. The forested trails are always tranquil and uncrowded, and it is interesting to see the residential structures up close, which contain little more than bedrooms and tombs, as cooking was done in separate open-air common kitchens.

Most of the sculpture has been removed, but one remaining piece is the Hieroglyphic Wall on Structure 82, a group of 16 glyphs cut in 786, relating events from the reign of Yax Pac, Copán’s last ruler. On the same structure is a portrait of Puah Tun, the patron of scribes, seated with a seashell ink holder in one hand and a writing tool in the other.

In Plaza A of Las Sepulturas, the tomb of a powerful shaman who lived around 450 was discovered; it can be seen in its entirety in the Museo Regional de Arqueología in Copán Ruinas. In this same area, traces of inhabitation dating from 1000 b.c., long predating the Copán dynasty, were found.

Las Sepulturas is connected to the principal group of ruins by an elevated road, called a sacbé, which runs through the woods. The road passes through private property, so visitors must go around by the highway. Be sure to bring your ticket from the main ruins, as you must show it to get into Las Sepulturas.

The men hanging out at the entrance offering guide service are highly knowledgeable, some having formerly worked as excavators, and their explanations help bring the ruins to life. Whether you use one of these guides or bring someone from the main site, you can expect to pay US$15 for the service.

In the hills on the far side of the Río Copán, just opposite the ruins, is the small site of Los Sapos (The Toads). Formerly, this rock outcrop carved in the form of a frog must have been quite impressive, but the years have worn down the sculpture considerably. Right near the frog carving, and even harder to make out, is what might be the figure of a large woman with her legs spread, as if giving birth. Because of this second carving, archaeologists believe the location was a birthing spot, where Mayan women would come to deliver children. Although the carvings are not dramatic, the hillside setting above the Río Copán valley, across from the main ruins site, is lovely and makes a good two- to three-hour trip on foot or horseback. To get there, leave town heading south and follow the main road over the Río Copán bridge. On the far side, turn left and follow the dirt road along the river’s edge. A little farther on, the road forks—follow the right side uphill a couple hundred meters to Hacienda San Lucas. You can also hire a mototaxi to take you here from town for a couple of bucks. The ranch owners have built a small network of trails for visitors to wander along and admire the views, thick vegetation, and noisy bird life. Entrance is US$2. At the hacienda is a restaurant serving excellent traditional Honduran countryside food with products made by hand on the farm, like tasty fresh cheese, and a spectacular five-course dinner with revived Mayan recipes (reservations recommended). There are upscale guest rooms here too, if you’d like to stay for a night.

Higher up in the mountains beyond Los Sapos is another site, known as La Pintada, a single glyph-covered stela perched on the top of a mountain peak, still showing vestiges of its original red paint. The views out over the Río Copán valley and into the surrounding mountains are fantastic, particularly in the early morning. The site is near the village of the same name. Handicrafts are the specialty of the indigenous women here, who do backstrap weaving and make the corn husk dolls that are sold in town. By foot or horseback, La Pintada is about 2–3 hours from Copán Ruinas. Take the same road to Los Sapos, but stay left along the river instead of turning up to Rancho San Carlos. The road winds steadily up into the mountains, arriving at a gate. From here, it’s a 25-minute walk to the hilltop stela. It’s best to hire one of the many guides for a negotiable fee in Copán Ruinas to take you there either by foot or on horseback to ensure you don’t take a wrong turn. The Asociación de Guías Copán also offers tours to the site, and Yaragua offers combination tours to La Pintada and Los Sapos.

Eighteen kilometers northeast of the Copán ruins, the Río Amarillo (yellow river) archaeological park has been excavated, opening just in time for the “end of the world” celebrations in Copán in 2012. The park spans roughly 30 acres and contains Mayan ruins within a forest preserve. The five stone structures, a central staircase, and a large mask are easily accessed along trails. According to local archaeologists, the structures are from the Late Classic period of the Mayan empire (roughly a.d. 600–900), with a ceremonial center built after the fall of 18 Rabbit.

Another site unearthed in preparation for 2012, Rastrojón has been excavated under the direction of renowned Copán archaeologist William Fash, with the support of Harvard University. Located to the north of Copán Ruinas, vestiges include a temple built in honor of Smoke Jaguar, one of the great warriors of Copán, and a large quantity of mosaic sculpture.

On the far side of the Río Copán valley is Stela 10, another mountaintop stela, which lines up with La Pintada during the spring and fall equinoxes. Covered with glyphs, some of them badly eroded, the stela stands about 2.5 meters high. To get there, drive or walk 4.5 kilometers from Copán Ruinas on the road to Guatemala, and look for a broad, well-beaten trail heading uphill to the right, which leads to the stela in a 10-minute hike. This stela can be easily found without a guide. For those without a car, catch a ride to the trail turnoff with one of the frequent pickup trucks traveling to the Guatemalan border.

Excerpted from the Sixth Edition of Moon Honduras & the Bay Islands.