Panoramic view of Tegucigalpa. Photo © Ian Mackenzie, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

Honduras’s capital, a city of just over one million inhabitants, occupies a high mountain valley around 1,000 meters above sea level, with the Río Choluteca running right down the middle. The valley is ringed by mountains, with a narrow opening to the north allowing the Río Choluteca to continue on its convoluted course to the Pacific Ocean 130 kilometers away. Among Tegucigalpa’s tourist attractions are several colonial churches, three museums, a number of markets, and plenty of handicraft stores, most in the downtown area.Opinions of Tegucigalpa—called “Tegus” (Tay-goose) by locals—vary wildly. Some visitors are uninspired and can’t wait to catch the next bus out of town, while others are charmed by the mix of colonial and modern buildings, the mountain setting, and its many services.Among Tegucigalpa’s tourist attractions are several colonial churches, three museums, a number of markets, and plenty of handicraft stores, most in the downtown area.

Because of its altitude, Tegucigalpa has a pleasant climate year-round, generally warm during the day and cool at night, and the mean annual temperature is 28°C (82°F). September through November can be a bit cooler with some rain, and the coldest month is January, when frentes fríos, cold north winds, pass through town. Pollution can get heavy in March and April, the time in which farmers in the hills follow centuries-old slash-and-burn agricultural techniques.

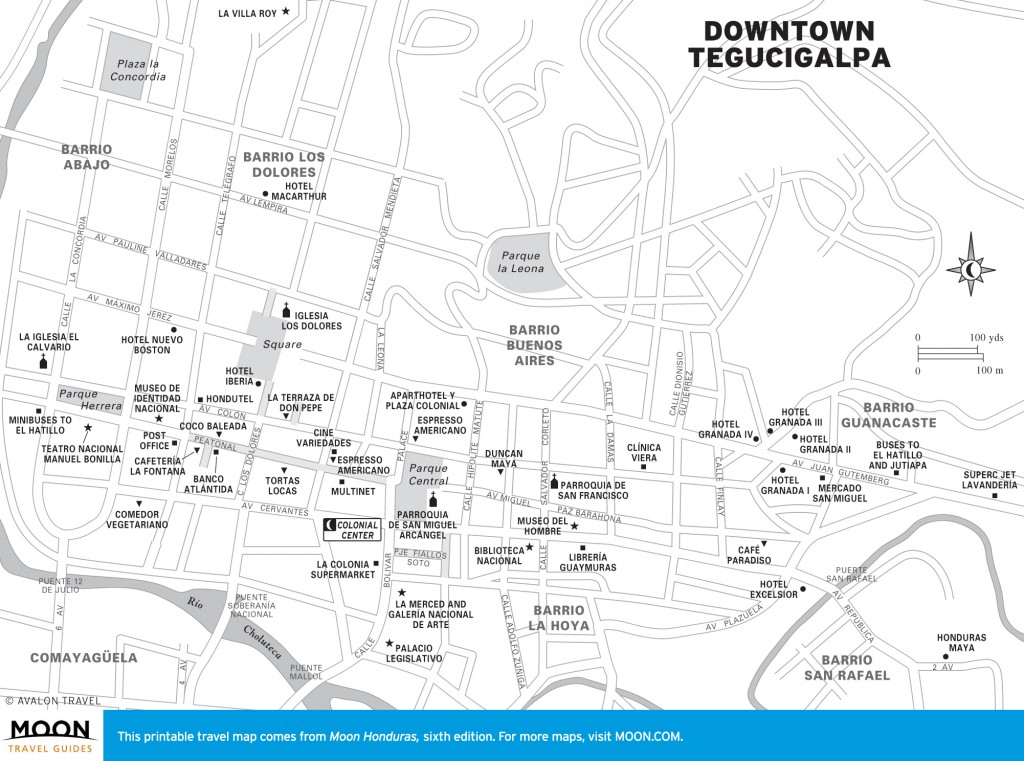

Downtown Tegucigalpa

Both archaeological work and historical records suggest the Tegucigalpa valley was not a major population center, at least in the years shortly before the Spanish conquest. It’s postulated that the mainly Lenca population was dependent on the larger settlements in the nearby Comayagua valley. Many believe the city’s name derives from the Lenca words meaning “land of silver,” but the Lenca had no interest in silver and are not likely to have named a place because of it. Others have suggested “place of the painted rocks” and “place where the men meet.” The ending “galpa,” common in the region, means “place” or “land.” In the early 1540s at the latest, Spanish conquistador Alonso de Cáceres likely passed through the region on his way to Olancho under orders from Francisco Montejo, but he made no report on the valley. It’s probable that residents of Comayagua, who were combing the new colony for precious metals, found the first veins of silver near Santa Lucía by 1560. An official report to the Spanish authorities dated 1589 states silver was found in Tegucigalpa 12-15 years prior. According to local legend, the first strike was made on September 29, Saint Michael’s day; hence, San Miguel is the city’s patron saint.

Whatever the exact date, by the late 16th century, miners were building houses and mine operations along the Río Choluteca and in the hills above. Tegucigalpa had no formal founding, like Comayagua, Gracias, or Trujillo, but grew haphazardly and remained a small settlement of dispersed houses connected by trails for the first years of its existence. The original name for the settlement was Real de Minas de San Miguel de Tegucigalpa, but by 1768 the mines were producing enough wealth to merit the title “Villa.”

By the end of the colonial period, the city’s mineral wealth eclipsed Comayagua in economic importance. Because of the rivalry between the two cities, the legislature of the short-lived Central American Republic alternated between the two, and in 1880 President Marcos Aurelio Soto moved the capital definitively to Tegucigalpa. Some say Soto made the move out of anger toward the Comayagua aristocracy for snubbing his indigenous wife, but more likely he was following his liberal principles by locating the government where the economy was strongest.

In the early 20th century, Honduras’s economic expansion was centered on the north coast, and the lack of a cross-country railroad left Tegucigalpa behind in development. The mines at El Rosario provided some stimulus, but most of the profits went to New York rather than Tegucigalpa. To this day, Tegucigalpa has no major industry to speak of and survives mainly through the government, the service industry, a small financial community, and a handful of maquilas on the outskirts of town. In 1932, the Distrito Central was created, bringing neighboring Comayagüela and Tegucigalpa under a unified government.

Downtown Tegucigalpa is arranged around the parque central (central square), with the Parroquia de San Miguel Arcángel (known simply as la Catedral) on the east side. Most of the city’s government and business buildings were formerly located in the downtown area, but many have since moved out to Miraflores, Avenida Juan Pablo II, and other parts of the city, no doubt partly to escape the abysmal traffic. Most of the sights of interest to tourists are within walking distance of the parque central. Because of the city’s broken geography and haphazard construction over the centuries, Tegucigalpa does not have an ordered street plan and can be a bit confusing to navigate at first (a problem vastly compounded by the lack of street signs in many neighborhoods).

East and uphill from downtown are Barrio San Rafael and Colonia Palmira, the first modern, wealthy neighborhoods developed in Tegucigalpa and home to many of the city’s embassies, high-priced hotels, and nicer restaurants. Farther east continue Avenida La Paz, home to the imposing U.S. Embassy building, and the parallel Boulevard Morazán, with many shops, restaurants, and mini-malls. Avenida La Paz turns into Avenida Los Proceres at its eastern end, where it leads to the exit to Santa Lucía and Valle de Ángeles. Southeast of downtown extends Avenida Juan Pablo II, where the Clarion and Inter-Continental Hotels and the glitzy Mall Multiplaza are located, and Boulevard Suyapa, which leads to the Basílica de Suyapa and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras. Cutting across the south part of the city, connecting the San Pedro Sula exit to the highway leading east to Danlí, is the fast-moving Boulevard Fuerzas Armadas.

Across the Río Choluteca from downtown is Comayagüela, a noisier and poorer sister city to Tegucigalpa. The main city market and almost all of the long-distance bus stations are in Comayagüela. Some travelers may find it convenient and inexpensive to stay in Comayagüela, but avoid walking around after dark (and be on alert during the day).

Most budget travelers will end up staying in downtown Tegucigalpa, where inexpensive accommodations and food are available, and head over to Comayagüela for transport in and out of town. Travelers with a bigger budget, or those in Tegucigalpa for work, will spend most of their time in Colonia Palmira, on Boulevard Morazán and Avenida Juan Pablo II, for the higher-end restaurants and hotels.

Like any big city in a poor country, Tegucigalpa can be a dangerous place. The great majority of visitors will have no problems at all, but muggings are a concern throughout the city. And remember, personal safety is always more valuable than anything you might be carrying. So should you be unlucky enough to be confronted by a mugger, give them what they ask for and do not resist. Be aware that the upscale neighborhood Colonia Palmira has become a popular spot for muggings, where would-be thieves are especially on the lookout for people with cell phones or laptops, and people walking alone. There are tourist police (as well as regular) throughout the historic center, and it is fine to walk around downtown during the day. Comayagüela is well known as the most dangerous part of the capital, although the worst areas are neighborhoods where travelers are unlikely to visit, such as Carrizal along the hillside-walking on the main streets during the day shouldn’t be a problem. The market is a haven for gangsters charging their “war tax” and is best avoided. Avoid walking after dark anywhere in the city.

One mugging tactic is to have two persons on a motorcycle, which slows as it passes you, and the rider yanks your purse or pack off your shoulder. Keep packs on both shoulders and purses with the strap over one shoulder and crossing your body, or keep your bag on the shoulder away from the street to make yourself less of a target for this type of mugging.

The smaller towns and countryside areas near Tegucigalpa mentioned in this guide, like Santa Lucía, Valle de Ángeles, Ojojona, Yuscarán, and La Tigra National Park, are all very safe.

Excerpted from the Sixth Edition of Moon Honduras & the Bay Islands.