The Maya ruins of Cobá make an excellent complement—or even alternative—to the memorable but vastly overcrowded ruins at Tulum. Cobá doesn’t have Tulum’s stunning Caribbean view and beach, but its structures are much larger and more ornate—in fact, Cobá’s main pyramid is the second tallest in the Yucatán Peninsula, and it’s one of few you are still allowed to climb. The ruins are also surrounded by lakes and thick forest, making it a great place to see birds, butterflies, and tropical flora.

Mayan Nohoch Mul pyramid in Coba, Mexico. Photo © Nataliya Hora/123rf.

Cobá (8am-5pm daily, US$4.50) is especially notable for the complex system of sacbeob, or raised stone causeways, that connected it to other cities, near and far. (The term sacbeob—whose singular form is sacbé—means white roads.) Dozens of such roads crisscross the Yucatán Peninsula, but Cobá has more than any other city, underscoring its status as a commercial, political, and military hub. One road extends in an almost perfectly straight line from the base of Cobá’s principal pyramid to the town of Yaxuna, more than 100 kilometers (62 miles) away—no small feat considering a typical sacbé was 1-2 meters (3.3-6.6 feet) high and about 4.5 meters (15 feet) wide, and covered in white mortar. In Cobá, some roads were even bigger—10 meters (32.8 feet) across. In fact, archaeologists have uncovered a massive stone cylinder believed to have been used to flatten the broad roadbeds.

Cobá was settled as early as 100 BC around a collection of small lagoons; it’s a logical and privileged location, as the Yucatán Peninsula is virtually devoid of rivers, lakes, or any other aboveground water. Cobá developed into an important trading hub, and in its early existence had a particularly close connection with the Petén region of present-day Guatemala. That relationship would later fade as Cobá grew more intertwined with coastal cities like Tulum, but Petén influence is obvious in Cobá’s high steep structures, which are reminiscent of those in Tikal.

At its peak, around AD 600-800, Cobá was the largest urban center in the northern lowlands, with some 40,000 residents and over 6,000 structures spread over 50 square kilometers (31 square miles). The city controlled most of the northeastern portion of the Yucatán Peninsula during the same period before being toppled by the Itzás of Chichén Itzá following a protracted war in the mid-800s. Following a widespread Maya collapse—of which the fall of Cobá was not the cause, though perhaps an early warning sign—the great city was all but abandoned, save as a pilgrimage and ceremonial site for the ascendant Itzás. It was briefly reinhabited in the 12th century, when a few new structures were added, but had been abandoned again, and covered in a blanket of vegetation, by the time of the Spanish conquest.

Passing through the entry gate, the first group of ruins you encounter is the Cobá Group, a collection of over 50 structures and the oldest part of the ancient city. Many of Cobá’s sacbeob initiate here. Its primary structure, La Iglesia (The Church), rises 22.5 meters (74 feet) from a low platform, making it Cobá’s second-highest pyramid. The structure consists of nine platforms stacked atop one another and notable for their round corners. Built in numerous phases beginning in the Early Classic era, La Iglesia is far more reminiscent of Tikal and other Petén-area structures than it is of the long palaces and elaborate facades typical of Puuc and Chenes sites. Visitors are no longer allowed to climb the Iglesia pyramid due to the poor state of its stairs, but it is crowned with a small temple where archaeologists discovered a cache of jade figurines, ceramic vases, pearls, and conch shells.

The Cobá Group also includes one of the city’s two ball courts, and a large acropolis-like complex with wide stairs leading to raised patios. At one time these patios were connected, forming a long gallery of rooms that likely served as an administrative center. The best-preserved structure in this complex, Structure 4, has a long vaulted passageway beneath its main staircase; the precise purpose of this passageway is unclear, but it’s a common feature in Cobá and affords a close look at how a so-called Maya Arch is constructed.

![Stella 12 from Structure 4 Passageway. Photo © Greg Willis from Denver, CO, USA [<a href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0">CC BY-SA 2.0</a>], <a href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AStella_12_from_Structure_4_Passageway_(8408076695).jpg">via Wikimedia Commons</a>.](https://www.holidaytravel.cc/Article/UploadFiles/201602/2016021615413610.jpg)

Stella 12 from Structure 4 Passageway. Photo © Greg Willis from Denver, CO, USA [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

The Cobá Group is directly opposite the stand where you can rent bicycles or hire bike taxis. Many travelers leave it for the end of their visit, after they’ve turned in their bikes.From the Cobá Group, the path winds nearly two kilometers (1.2 miles) through dense forest to Cobá’s other main group, Nohoch Mul. The name Nohoch Mul is Yucatec Maya for Big Mound—the group’s namesake pyramid rises an impressive 42 meters (138 feet) above the forest floor, the equivalent of 12 stories. (It was long believed to be the Yucatán Peninsula’s tallest structure until the main pyramid at Calakmul in Campeche was determined to be some 10 meters higher.) Like La Iglesia in the Cobá Group, Nohoch Mul is composed of several platforms with rounded corners. A long central staircase climbs steeply from the forest floor to the pyramid’s lofty peak. A small temple at the top bears a fairly well-preserved carving of the Descending God, an upside-down figure that figures prominently at Tulum but whose identity and significance is still unclear. (Theories vary widely, from Venus to the god of bees.)

Nohoch Mul is one of few Maya pyramids that visitors are still allowed to climb, and the view from the top is impressive—a flat green forest spreading almost uninterrupted in every direction. A rope running down the stairs makes going up and down easier. Where the path hits Nohoch Mul is Stela 20, positioned on the steps of a minor structure, beneath a protective palapa roof. It is one of Cobá’s best-preserved stelae, depicting a figure in an elaborate costume and headdress, holding a large ornate scepter in his arms—both signifying that he is an ahau, or high lord or ruler. The figure, as yet unidentified, is standing on the backs of two slaves or captives, with another two bound and kneeling at his feet. Stela 20 is also notable for the date inscribed on it—November 30, 780—the latest Long Count date yet found in Cobá.

Between the Cobá and Nohoch Mul Groups are several smaller but still significant structures. Closest to Nohoch Mul is a curiously conical structure that archaeologists have dubbed Xaibé, a Yucatec Maya word for crossroads. The name owes to the fact that it’s near the intersection of four major sacbeob, and for the same reason, archaeologists believe it may have served as a watchtower. That said, its unique design and imposing size suggest a grander purpose. Round structures are fairly rare in Maya architecture, and most are thought to be astronomical observatories; there’s no evidence Xaibé served that function, however, particularly since it lacks any sort of upper platform or temple. Be aware that the walking path does not pass Xaibé—you have to take the longer bike path to reach it.

Xaibe – The Crossroads Pyramid – in Cobá. Photo © Dennis Jarvis, licensed CC-BY.

A short distance from Xaibé is the second of Cobá’s ball courts. Both courts have imagery of death and sacrifice, though they are more pronounced here: a skull inscribed on a stone in the center of the court, a decapitated jaguar on a disc at the end, and symbols of Venus (which represented death and war) inscribed on the two scoring rings. This ball court also had a huge plaque implanted on one of its slopes, with over 70 glyphs and dated AD 465; the plaque in place today is a replica, but the original is under a palapa covering at one end of the court, allowing visitors to examine it more closely.

The Paintings Group is a collection of five platforms encircling a large plaza. The temples here were among the last to be constructed in Cobá and pertain to the latest period of occupation, roughly AD 1100-1450. The group’s name comes from paintings that once lined the walls, though very little color is visible now, unfortunately. Traces of blue and red can be seen in the upper room of the Temple of the Frescoes, the group’s largest structure, but you aren’t allowed to climb up to get a closer look.

Although centrally located, the Paintings Group is easy to miss on your way between the more outlying pyramids and groups. Look for a sign for Structure 5, where you can leave your bike (if you have one) and walk into the group’s main area.

From the Paintings Group, the path continues southeasterly for about a kilometer (0.6 mile) to the Macanxoc Group. Numerous stelae have been found here, indicating it was a place of great ceremonial significance. The most famous of these monuments is Stela 1, aka the Macanxoc Stela. It depicts a scene from the Maya creation myth—”the hearth stone appears”—along with a Long Count date referring to a cycle ending the equivalent of 41.9 billion, billion, billion years in the future. It is the most distant Long Count date known to have been conceived and recorded by the ancient Maya. Stela 1 also has reference to December 21, 2012, when the Maya Long Count completed its first Great Cycle, equivalent to 5,125 years. Despite widespread reports to the contrary, there is no known evidence, at Cobá or anywhere, that the Maya believed (much less predicted) that the world would end on that date.

Cobá’s main groups are quite spread apart, and visiting all of them adds up to several kilometers. Fortunately, you can rent a bicycle (US$3) or hire a triciclo (US$9.50 for 80 minutes, US$15 for 2 hours) at a large stand a short distance past the entryway, opposite the Cobá Group. Whether you walk or ride, don’t forget a water bottle, comfortable shoes, bug repellent, sunscreen, and a hat. Watch for signs and stay on the designated trails. Guide service is available—prices are not fixed but average US$52 per group (1.5 hours, up to 6 people). Parking at Cobá is US$3.

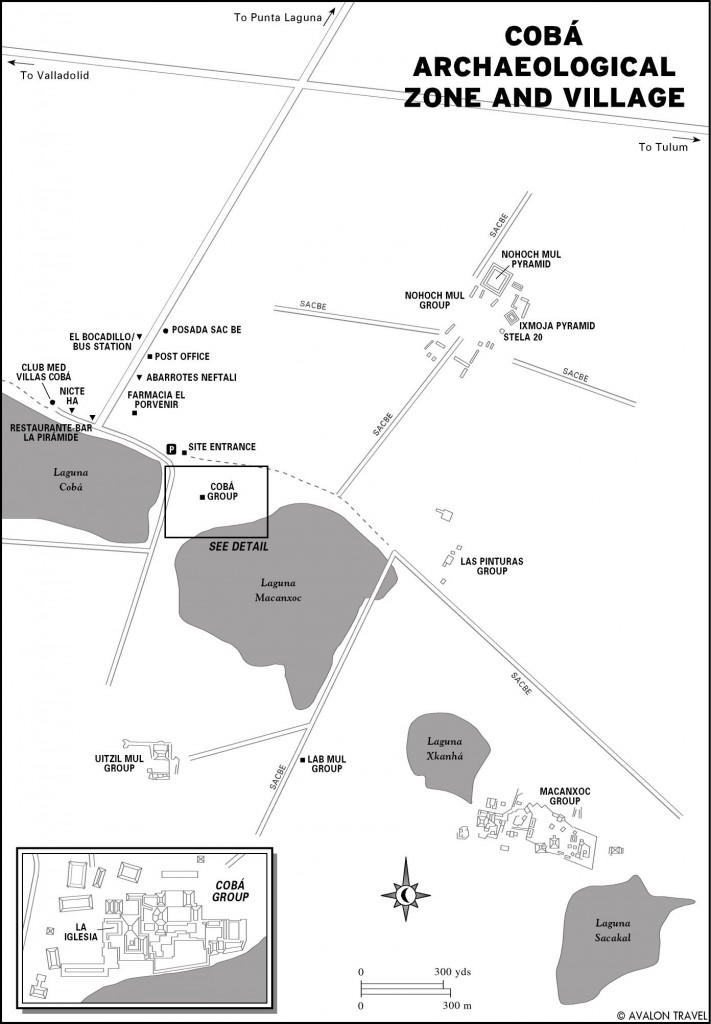

Map of Cobá, Mexisco.

Cobá is not nearly as crowded as Tulum (and is much larger), but it’s still a good idea to arrive as early as possible to beat the ever-growing crowds.

Excerpted from the Twelfth Edition of Moon Cancun & Cozumel.