Sunset in Panama City’s Casco Viejo. Photo © Ana Freitas, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

Casco Viejo has always had a romantic look, but for decades the romance has been of the tropical-decadence, paint-peeling-from-the-walls variety. Since the 1990s, though, it’s been undergoing a tasteful and large-scale restoration that’s giving the old buildings new luster and has turned the area into one of the city’s most fashionable destinations for a night out. Elegant bars, restaurants, and sidewalk cafés have opened. Hotels and hostels are arriving. Little tourist shops are popping up. Amazingly, this is being done with careful attention to keeping the old charm of the place alive. Unfortunately, the renovation is squeezing out the poorer residents who’ve lived here for ages. [Casco Viejo’s] buildings feature an unusual blend of architectural styles, most notably rows of ornate Spanish and French colonial houses but also a smattering of art deco and neoclassical buildings.The “Old Part,” also known as Casco Antiguo or the San Felipe district, was the second site of Panama City, and it continued to be the heart of the city during the first decades of the 20th century. UNESCO declared it a World Heritage Site in 1997. It’s a city within the city—940 buildings, 747 of which are houses—and one from a different age. It’s a great place for a walking tour. You can wander down narrow brick streets, sip an espresso at an outdoor café, visit old churches, and gaze up at wrought-iron balconies spilling over with bright tropical plants. Its buildings feature an unusual blend of architectural styles, most notably rows of ornate Spanish and French colonial houses but also a smattering of art deco and neoclassical buildings.In some respects Sunday is a good day for exploring Casco Viejo. For one thing, it’s the likeliest time to find the churches open and in use. However, though more bars and restaurants are now staying open on Sunday, most aren’t, and even some of the museums are closed. Several places are also closed on Monday. Getting a look inside historic buildings and museums is easiest during the week, especially since some are in government offices open only during normal business hours. Churches open and close rather erratically.

Casco Viejo

Even with the makeover, Casco Viejo is not the safest part of Panama City. Ironically, the area’s renaissance seems to be driving crime: With more tourists and affluent residents in Casco Viejo, there’s more appeal for criminals.

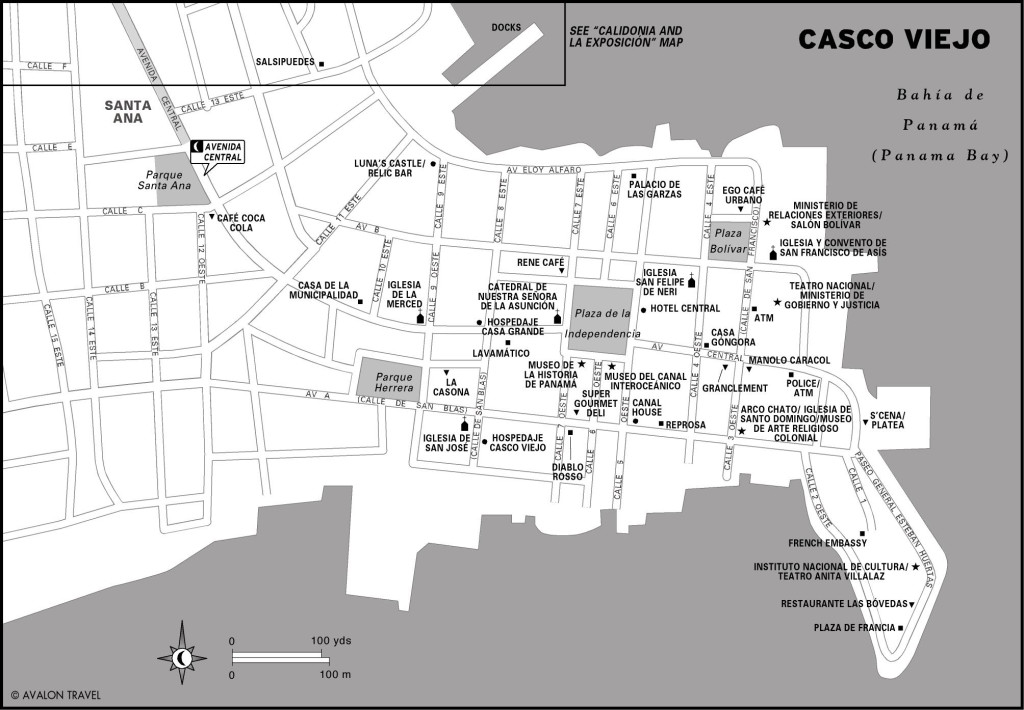

There’s no reason to be overly concerned, but use common sense and try not to stand out. If you’re pale and gringo, try to look as though you’re a resident foreigner. Don’t wander around at night, and be cautious when venturing beyond the major hubs of activity (Plaza Bolívar, Plaza de la Independencia, and Plaza de Francia). Look at the map of Casco Viejo and mentally draw a line from Luna’s Castle to Parque Herrera: At night, do not venture west of this area on foot. Also avoid the block of Calle 4 between Avenida Central and Avenida B at night. Parque Herrera is still on the edge of a sketchy area.

The neighborhood is well patrolled by the policía de turismo (tourism police), who cruise around on bicycles and are easy to spot in their short-pants uniforms. They’ve been trained specifically to serve tourists, and they’re doing an impressive job. It’s not unusual for them to greet foreign tourists with a handshake and a smile and offer them an insider’s tour of the area or help with whatever they need. Don’t hesitate to ask them for help or directions. Their station is next to Manolo Caracol and across the street from the Ministerio de Gobierno y Justicia (Avenida Central between Calle 2 Oeste and Calle 3 Este, tel. 211-2410 or 211-1929). It’s open 24 hours, and the officers will safely guide you to your destination night or day.

There’s a heavy police presence around the presidential palace, but those police are stern and no-nonsense. Their job is to protect the president, not help tourists.

In the center of Casco Viejo is the Plaza de la Independencia, where Panama declared its independence from Colombia in 1903. This area was the center of Panama City until the early 20th century. The buildings represent a real riot of architectural styles, from neo-Renaissance to art deco. Construction began on the cathedral, the Catedral de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, in 1688, but it took more than 100 years to complete. Some of the stones used come from the ruins of Panamá La Vieja. It has an attractive marble altar and a few well-crafted stained-glass windows, though otherwise the interior is rather plain. The towers are inlaid with mother-of-pearl from the Perlas Islands. The bones of a saint, Santo Aurelio, are contained in a reliquary hidden behind a painting of Jesus near the front of the church, on the left as one faces the altar.

The Museo del Canal Interoceánico (Avenida Central between Calle 5 Oeste and Calle 6 Oeste, tel. 211-1995 or 211-1649, 9 a.m.–5 p.m. Tues.–Sun, US$2 adults, US$0.75 students) is dedicated to the history of the Panama Canal. The museum is housed in what started life as the Grand Hotel in 1874, then became the headquarters of the French canal-building effort, and later spent the early part of the 20th century as the capital’s central post office. It’s worth a visit, but be prepared for some frustration if you don’t speak Spanish. Everything is Spanish only, which is significant since the exhibits often consist more of text than anything else. However, an audio guide in English, Spanish, and French is available. The displays tell the story of both the French and American efforts to build the canal, and throw in a little bit of pre-Columbian and Spanish colonial history at the beginning. There’s some anti-American propaganda, and most of what’s written about the canal from the 1960s on should be taken with a big chunk of salt. There’s a good coin collection upstairs, as well as a few Panamanian and Canal Zone stamps. There’s also a copy of the 1977 Torrijos-Carter Treaties that turned the canal over to Panama. You can tour the whole place in about an hour.

The Museo de la Historia de Panamá (Avenida Central between Calle 7 Oeste and Calle 8 Oeste, tel. 228-6231, 8 a.m.–4 p.m. Mon.–Fri., US$1 general admission, US$0.25 children) is a small museum containing artifacts from Panama’s history from the colonial period to the modern era. It’s in the Palacio Municipal, a neoclassical building from 1910 that is now home to government offices. At first glance it seems like just another one of Panama’s woefully underfunded museums housing a few obscure bits of bric-a-brac. But anyone with some knowledge of Panama’s history—which is essential, since the Spanish-only displays are poorly explained—will find some of the displays fascinating.

Among these are a crudely stitched Panama flag, said to have been made by María Ossa de Amador in 1903. She was the wife of Manuel Amador Guerrero, a leader of the revolutionaries who conspired with the Americans to wrest independence from Colombia. The flag was hastily designed by the Amadors’ son, and the women in the family sewed several of them for the rebels; the sewing machine they used is included in the display. If the revolution had failed, this quaint sewing circle might have meant death by hanging for all of them. Instead, Manuel Amador became the first president of Panama.

On a desk by the far wall is the handwritten draft of a telegram the revolutionaries sent to the superintendent of the Panama Railroad in Colón, pleading with him not to allow Colombian troops from the steamship Cartagena to cross the isthmus and put down the revolution. This was one of the tensest moments in the birth of Panama. In the end, they didn’t cross over, and the revolution was nearly bloodless. The telegram is dated November 3, 1903, the day Panama became independent, and those who sent it are now considered Panama’s founding fathers.

Other displays include a stirrup found on the storied Camino de Cruces, a plan for the fortifications built at Portobelo in 1597, 17th-century maps of the “new” Panama City at Casco Viejo (note the walls that originally ringed the city, now all but gone), and the sword of Victoriano Lorenzo, a revered hero of the War of a Thousand Days.

The church with the crumbling brown facade and whitewashed sides near the corner of Avenida Central and Calle 9 Oeste is Iglesia de la Merced, which was built in the 17th century from rubble salvaged from the ruins of Panamá La Vieja. It’s worth a quick stop for a look at its wooden altars and pretty tile floor. The neoclassical building next to it, the Casa de la Municipalidad, is a former mansion now used by the city government.

The little park, Parque Herrera, was dedicated in 1976. The statue of the man on horseback is General Tomás Herrera, an early hero of Panama’s complex independence movements. Some of the historic buildings ringing the park are undergoing major renovation, with at least three hotels planned for the area.

The golden altar in Casco Viejo’s Iglesia de San José. Photo © Brian Gratwicke, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

The massive golden altar (altar de oro) is a prime tourist attraction at Iglesia de San José (Avenida A between Calle 8 and Calle 9, 7 a.m.– noon and 2–8 p.m. Mon.–Sat., 5 a.m.–noon and 5–8 p.m. Sun.). Legend has it that the altar was saved from the rapacious Welsh pirate Henry Morgan during the sacking of the original Panama City when a quick-thinking priest ordered it painted black, hiding its true value.

The original Iglesia de Santo Domingo (Avenida A and Calle 3 Oeste) was built in the 17th century, but it burned twice and was not rebuilt after the fire of 1756. It remains famous for one thing that survived, seemingly miraculously: the nearly flat arch (Arco Chato). Since it was built without a keystone and had almost no curve to it, it should have been a very precarious structure, yet it remained intact even as everything around it fell into ruins. One of the reasons a transoceanic canal was built in Panama was that engineers concluded from the intact arch that Panama was not subject to the kinds of devastating earthquakes that afflict its Central American neighbors.

On the evening of November 7, 2003, just four days after Panama celebrated its first centennial as a country, the arch finally collapsed into rubble. It has since been rebuilt, but its main appeal, its gravity-defying properties through the centuries, can never be restored. The church itself is undergoing a slow restoration.

The Plaza de Francia (French Plaza) has seen a great deal of history and was among the first parts of Casco Viejo to be renovated, back in 1982.

The obelisk and the marble plaques along the wall commemorate the failed French effort to build a sea-level canal in Panama. The area housed a fort until the beginning of the 20th century, and the bóvedas (vaults) in the seawall were used through the years as storehouses, barracks, offices, and jails. You’ll still hear gruesome stories about dungeons in the seawall, where prisoners were left at low tide to drown when the tide rose. Whether this actually happened is still a subject of lively debate among amateur historians. True or not, what you will find there now is one of Panama’s more colorful restaurants, Restaurante Las Bóvedas. Also in the plaza are the French Embassy, the headquarters of the Instituto Nacional de Cultura (INAC, the National Institute of Culture) in what had been Panama’s supreme court building, and a small theater, Teatro Anita Villalaz. Tourists are not allowed into the grand old building that houses INAC, but it’s worth peeking into from the top of the steps or the lobby, if you can get that far. Note the colorful, if not particularly accomplished, mural depicting idealized versions of Panama’s history. (The building was used as a set for the 2008 James Bond film Quantum of Solace, as were the ruins of the old Union Club.) Next to the restaurant is an art gallery (tel. 211-4034, 9:30 a.m.–5:30 p.m. Tues.–Sat.) run by INAC that displays works by Panamanian and other Latin American artists.

Walk up the staircase that leads to the top of the vaults. This is part of the old seawall that protected the city from the Pacific Ocean’s dramatic tides. There’s a good view of the Panama City skyline, the Bridge of the Americas, and the Bay of Panama, and the breeze is great on a hot day. The walkway, Paseo General Esteban Huertas, is shaded in part by a bougainvillea-covered trellis and is a popular spot with smooching lovers. Along the walkway leading down to Avenida Central, notice the building on the waterfront to the right. For years this has been a ruin, though there have long been plans to turn it into a hotel. This was once the officers’ club of the Panamanian Defense Forces; it was largely destroyed during the 1989 U.S. invasion. Before that, it was the home of the Union Club, a hangout for Panama’s oligarchy that’s now on Punta Paitilla.

Built in 1756, the stone house of Casa Góngora (corner of Avenida Central and Calle 4, tel. 212-0338, 8 a.m.–4 p.m. Mon.–Fri., free) is the oldest house in Casco Viejo and one of the oldest in Panama. It was originally the home of a Spanish pearl merchant. It then became a church and has now been turned into a small, bare-bones museum. It’s had a rough history—it has been through three fires and the current wooden roof is new. A 20th-century restoration attempt was botched, causing more damage. There isn’t much here, but the staff can give free tours (in Spanish) and there have been noises about making it more of a real museum in the future. There’s an interesting, comprehensive book on the history of the house and neighborhood (again, in Spanish) that visitors are welcome to thumb through, containing rare maps, photos, and illustrations. Ask for it at the office. The museum hosts jazz and folkloric concerts and other cultural events in the tiny main hall on some Friday and Saturday nights, and occasionally hosts art shows.

Iglesia San Felipe de Neri (corner of Avenida B and Calle 4) dates from 1688 and, though it has also been damaged by fires, is one of the oldest standing structures from the Spanish colonial days. It was renovated in 2003, but is seemingly never open to the public.

The intimate Teatro Nacional (National Theater, between Calle 2 and Calle 3 on Avenida B, 9:30 a.m.–5:30 p.m. Mon.–Fri.) holds classical concerts and other posh events. It was built in 1908 on the site of an 18th-century monastery. It’s housed in the same building as the Ministerio de Gobierno y Justicia (Ministry of Government and Justice), which has its entrance on Avenida Central.

Inaugurated on October 1, 1908, the neo-baroque theater is worth a brief visit between concerts to get a glimpse of its old-world elegance. The public can explore it during the week but not on weekends. The first performance here was a production of the opera Aida, and for about 20 years the theater was a glamorous destination for the city’s elite. Note the bust of the ballerina Margot Fonteyn in the lobby; she married a Panamanian politician in 1955 and lived out the last part of her life in Panama.

The ceiling is covered with faded but still colorful frescoes of cavorting naked ladies, painted by Roberto Lewis, a well-known Panamanian artist. Leaks in the roof destroyed about a quarter of these frescoes, and the roof partially collapsed. The roof was restored and the theater reopened in 2004. Be sure to walk upstairs to take a look at the opulent reception rooms.

Plaza Bolívar (on Avenida B between Calle 3 and Calle 4) has been undergoing a charming restoration. It’s especially pleasant to hang out on the plaza in the evening, when tables are set up under the stars. It’s a good rest stop for a drink or a bite. A good café to check out is Restaurante Casablanca.

The plaza was named for Simón Bolívar, a legendary figure who is considered the father of Latin America’s independence from Spain. In 1826 Bolívar called a congress here to discuss forming a union of Latin American states. Bolívar himself did not attend and the congress didn’t succeed, but the park and the statue of Bolívar commemorate the effort.

The congress itself was held in a small, twostory building that has been preserved as a museum, now known as the Salón Bolívar (Plaza Bolívar, tel. 228-9594, 9 a.m.–4 p.m. Tues.–Sat., 1–5 p.m. Sun., US$1 adults, US$0.25 students).

While the museum is designed attractively, there’s not much in it. The room upstairs contains the text of the protocols of different congresses called during the independence movement. There’s also a replica of Bolívar’s jewel-encrusted sword, a gift from Venezuela (the original is now back in Venezuela). The actual room where the congress took place is on the ground floor.

The little museum is entirely enclosed by glass to protect it and is actually in the courtyard of another building, the massive Palacio Bolívar, which was built on the site of a Franciscan convent that dates from the 18th century. The building that houses the Salón Bolívar was originally the sala capitula (chapter house) of that convent, and is the only part of it that is still intact. The palacio dates from the 1920s and was a school for many years. Now it’s home to the Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores (Foreign Ministry). During regular business hours (about 8 a.m.–3 p.m. Mon.–Fri., 9 a.m.–1 p.m. Sat.), it’s possible, and well worthwhile, to explore the huge inner courtyard, which has been outfitted with a clear roof that’s out of keeping with the architecture, but protects it from the elements. The courtyard is open to the surf in the back, where part of the original foundation can be seen. Be sure to notice the beautiful tilework and the posh chandelier at the entrance.

Next door but still on the plaza is a church and former monastery, Iglesia y Convento de San Francisco de Asís. The church dates from the early days of Casco Viejo, but was burned during two 18th-century fires, then restored in 1761 and again in 1998. It’s an attractive confection on the outside, particularly its soaring tower, which is partly open-sided. It resembles a gothic wedding cake. It is not currently open to the public.

The presidential palace, El Palacio de las Garzas (Palace of the Herons), is on the left at Calle 5 Este, overlooking Panama Bay. It’s an attractive place that houses the presidential office and residence. Visitors are not permitted, and the palace and the neighboring streets are surrounded by guards. Everyone walking past the front of the palace must now go through a metal detector; they’re set up at either end of the street. Guards may ask for your passport, but more likely they will just wave you through after the cursory search. Be polite and deferential— they should let you walk by the palace. As you pass, sneak a peek at the courtyard through the palace’s front door, visible from the street, and try to spot the herons around the fountain.

A pedestrian path with great views links Casco Viejo to the city markets, running through the dockyard area known as known as the Terraplén. This is one of the more colorful and lively parts of the city. The path is part of the Cinta Costera along the Bay of Panama. Pedestrians, cyclists, and runners can enjoy great views of the bay, skyline, and fishing fleet while exploring the waterfront area. Four wide, busy lanes of the Cinta Costera separate the path from the densely packed and rather squalid streets of the Santa Ana and Santa Fé districts, making the path appealing even to the more safety-conscious.

For hundreds of years, small fishing boats have off-loaded their cargo around the Terraplén. These days fish is sold through the relatively clean, modern fish market, the two-story Mercado de Mariscos (5 a.m.–5 p.m. daily), on the waterfront just off the Cinta Costera on the way to Casco Viejo, right before the Mercado Público. This is an eternally popular place to sample ceviche made from an amazing array of seafood, sold at stalls around the market. There’s usually a line at Ceviches #2 (4:30 a.m.–5 p.m. daily), though whether it’s because the ceviche is truly better or because it’s simply closer to the entrance and open later than the other stalls is something I’ll leave to true ceviche connoisseurs. The large jars of pickled fish don’t make for an appetizing scene, but rest assured that ceviche is “cooked” in a pretty intense bath of onions, limes, and chili peppers. Prices for a Styrofoam cup of fishy goodness range from US$1.25 for corvina up to US$3.50 for langostinos. You shouldn’t leave Panama without at least trying some ceviche, whether here or somewhere a bit fancier.

Other stands, some with seating areas, are next to the main market building closer to the dock, but they tend to be smellier than the market. Those with sensitive noses will want to visit the area early in the morning, before the sun ripens the atmosphere.

Meat and produce are sold at the nearby Mercado Público (public market) on Avenida B, just off Avenida Eloy Alfaro near the Chinese gate of the Barrio Chino. The market is plenty colorful and worth a visit. It’s gated and has a guard at the entrance.

The meat section, though cleaner, is still not fully air-conditioned, and the humid, cloying stench of blood in the Panama heat may convert some to vegetarianism. The abarrotería (grocer’s section) is less overwhelming and more interesting. Shelves are stacked with all kinds of homemade chichas (fruit juices), hot sauce, and honey, as well as spices, freshly ground coconut, duck eggs, and so on. The produce section is surprisingly small.

There’s a food hall (4 a.m.–3 or 4 p.m. daily) in the middle of the market. The perimeter is ringed with fondas (basic restaurants) each marked with the proprietor’s name. A heaping plateful costs a buck or two.

Lottery vendors set up their boards along the walls by the entrance, and across the gated parking lot is a line of shops selling goods similar to and no doubt intended to replace those on the Terraplén. These include hammocks, army-surplus and Wellington boots, machetes, camping gear, and souvenirs such as Ecuadorian-style Panama hats. Each store keeps different hours, but most are open 8 a.m.–4 p.m. Monday–Saturday, and some are open Sunday mornings.

The market is staffed with friendly, uniformed attendants who can explain what’s going on, especially if you speak a bit of Spanish. There’s a Banco Nacional de Panamá ATM near the entrance.

Up Calle 13 is the crowded shopping area of Salsipuedes (a contraction of “get out if you can”). The area is crammed with little stalls selling clothes, lottery tickets, and bric-a-brac. Just north of this street is a small Chinatown, called Barrio Chino in Spanish. Most of the Chinese character of the place has been lost through the years; the ornate archway over the street is one of the few remaining points of interest.

There is one ATM in Casco Viejo, next to the tourism police station on Avenida Central near Calle 2. It’s best to come to Casco Viejo with sufficient cash.

Farmacia El Boticario (Avenida A and Calle 4 Oeste, tel. 202-6981, 8:30 a.m.–7 p.m. Mon.–Fri., 9 a.m.–6 p.m. Sat.) is Casco Viejo’s only pharmacy.

A good way to explore the area is to come with a knowledgeable guide or taxi driver who can drop you in different areas to explore on foot.

You’ll probably save time this way, as the streets are confusing and it’s easy to get lost. Do major exploring only during the daytime; those who come at night should taxi in and out to specific destinations. Restaurant and bar owners can call a cab for the trip back.

Even locals get lost here. Watch out for narrow one-way streets and blind intersections. Street parking is hard to find in the day and on weekend nights. There’s a paid lot with an attendant on the side of the Teatro Nacional that faces Panama Bay. It’s open 24 hours a day.

Excerpted from the Fourth Edition of Moon Panama.