The Azuero is a region of farmers, cattle ranchers, and, on the coast, fishermen. Photo © FutureExpat, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

The Azuero Peninsula

The Azuero Peninsula is a paradoxical place. It’s a heavily settled, terribly deforested land where wilderness has largely been supplanted by farms. In some places erosion has transformed forest into wasteland. Yet it still feels isolated from modern Panama, frozen in an idyllic past, and there’s lots of charm and natural beauty left. Oddly enough, it’s even home to one of Panama’s most pristine national parks. The Azuero is a land both much beloved and much abused.The Azuero is inevitably called Panama’s heartland, a designation that slights the country’s widely scattered indigenous populations, not to mention, for instance, those of African descent. Still, the peninsula occupies an important, almost mythological, place in the Panamanian psyche. It is the wellspring of Panama’s favorite folkloric traditions, many of which originated in Spain but have taken on a uniquely Panamanian form—often thanks, ironically enough, to borrowings from the above-mentioned indigenous and African peoples.

Beautiful traditional clothing, such as the stunning pollera (hand-embroidered dress), and handicrafts, such as ceramics based on pre-Columbian designs, originated and are still made on the Azuero. The same is true of some important musical and literary traditions. Even Panama’s national drink, the sugarcane liquor known as seco, is made here. Traces of Spanish-colonial Panama—rows of houses with red-tile roofs and ornate ironwork, centuries-old churches overlooking quiet plazas—are easy to find, especially in well-preserved little towns such as Parita and Pedasí.

Most of all, the Azuero is known for its festivals. It has the biggest and best in the country, from all-night bacchanals to sober religious rituals. At the top of the heap is Carnaval, held during the four days leading up to Ash Wednesday. No Latin American country outside of Brazil is more passionate about Carnaval than Panama, and no part of Panama is more passionate about it than the Azuero. Those who can’t—or don’t want to—experience Carnaval madness on the Azuero will likely have plenty of other spectacles to choose from. It’s rare for a single week to go by without some festival, fair, holy day, or other excuse for a major party somewhere on the peninsula.

For all the affection the Azuero inspires among Panamanians, most who live outside the peninsula know it only as a place to come for festivals. It flies below the radar of most foreign visitors altogether. But those who want a taste of an older, more stately Panama should consider a visit. In some places, it’s as though the 20th century never happened.

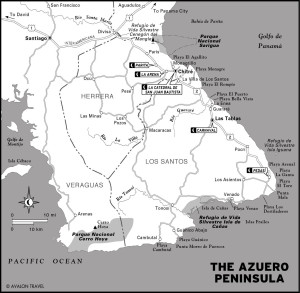

The Azuero is large enough to be shared by three provinces. The nearly landlocked Herrera province, Panama’s smallest, is to the north; Los Santos to the southeast has an extensive coastline ringing the eastern and southern sides of the peninsula; and huge Veraguas, the only province with a Caribbean and a Pacific coast, dips into the western side of the Azuero.

The Azuero is a region of farmers, cattle ranchers, and, on the coast, fishermen. Slash-and-burn agriculture and logging have been more extensive on the Azuero than in any other part of Panama, and the inevitable result has been both dramatic and sad. Deforestation has turned some parts of this region into barren desert, and most of the rest of it is pastureland.

Residents of Los Santos province are especially well-known for their tree-chopping prowess. Having cut down most of the trees in their own province, santeño farmers and cattle ranchers have spread out to deforest other parts of the country, including, most sadly of all, the forests of the Darién.

The hilly southwestern tip of the Azuero is the least developed, with a few patches of unspoiled wilderness left. These have until recently been extremely hard to get to, which is why they’re still lovely. The accessible lowland areas are now mostly farm country.

The east coast of the Azuero, as well as a strip of coast in Coclé province to the north, is known as the arco seco (dry arc), because of its lack of rainfall. While good news for sunbathers, that scarcity is bad news for the environment, showing the effects of creeping desertification.

The east-coast beaches resemble those within a couple of hours of Panama City, minus 30 years of development. They’re easy to get to, yet for dozens of kilometers at a stretch there’s little sign of human habitation. However, tourism has finally arrived in the area, though on a rather small scale so far. The most popular tourist destinations are Pedasí, Playa Venao, and, most recently, Cambutal. Some of the lodgings and tour operations are appealing. Others seem to exist primarily to create a market for real-estate sales. Buyer beware.

Don’t expect pure white sand on the Azuero. But those who don’t mind brown, gray, and in some cases black sand will have no trouble finding a deserted seaside paradise. The beaches are wide and long, often backed by rugged cliffs and facing rolling surf. Their waters are filled with big fish and, in some places, extensive coral. Isla de Cañas, off the south coast of the Azuero, is the most important nesting spot for sea turtles on Panama’s Pacific coast: Tens of thousands lay their eggs there each year.

The interior of the peninsula is taken up mostly by farmland, cattle pasture, and towns. There are few facilities for visitors there, but visiting this heart of the heartland is like stepping back in time.

The people of the Azuero are among the friendliest in Panama, and the percentage of smiles per capita seems to go up the farther south you head. People seem not just content but genuinely happy. It’ll probably rub off on you.

It’s possible to explore the biggest towns of the Azuero—Chitré and Las Tablas, which by Panamanian scale qualify as “cities”—and their surrounding attractions in a couple of days. It’s a straight shot, for instance, to pull off the road to take a quick look at Parita, shop for pottery in La Arena, visit La Catedral de San Juan Bautista and El Museo de Herrera in Chitré, then pop by La Villa de Los Santos before ending up in Las Tablas for dinner. Those who have their own transportation can do all that in a day. Those relying on buses and taxis, however, should plan on spending at least two days in the area, probably making Chitré home base for excursions to the surrounding area. And those who arrive during festival times should plan to stay longer than that, as many of the festivals last several days. The biggest Carnaval celebration is in Las Tablas; Chitré runs a close second. Bear in mind that just about everything shuts down during big celebrations. Add at least one more day to visit more remote destinations, especially along the coast, where you’ll want time to enjoy the beach.

The west coast of the Azuero is rather cut off from the rest of the peninsula, as there is only one main road, and it runs north-south between the outskirts of the city of Santiago down to Parque Nacional Cerro Hoya. The easiest and fastest way to travel between the east and west coasts of the Azuero is to head all the way back up to the Interamericana. The other option is to take the winding back roads which link the small towns and villages in the interior of the peninsula. It’s a more scenic but more time-consuming way to go.

Nearly the entire Azuero is well served by buses. Bus service between the peninsula and other parts of Panama is also good. Buses run constantly, for instance, to and from Panama City and Chitré and Las Tablas.

Las Tablas and Chitré are the major transportation hubs on the Azuero. They can be used as bases for exploring the east coast of the peninsula, but those looking for good beaches should head all the way down to Pedasí, near the southeast tip of the Azuero.

To drive to the Azuero Peninsula from Panama City, head west on the Interamericana until Divisa, which is little more than a crossroads. Divisa is about 215 kilometers from Panama City, a drive that takes around three hours. There’s an overpass across the highway there. Head south (left) here. Straight leads to Santiago and from there to western Panama.

Most of the notable towns in the Azuero are on a single main road, an ambitiously named carretera nacional (national highway) that runs down the east coast of the peninsula. The stretch of road from Divisa all the way to Pedasí is about 100 kilometers long and takes a little under two hours to drive. From Divisa as far as Las Tablas the road is a four-lane divided highway.

As is so often the case in Panama, it’s easy to drive right by a town that time forgot without noticing it. That’s because the part of the town abutting the main road is often quite ugly and industrial. It’s worth pulling off the highway or hopping off the bus from time to time to explore the older parts of the towns, which are set back from the road. The best bet for finding a slice of colonial quaintness is to head for the church and check out the buildings set around its plaza.

The interior of the peninsula has a confusing network of roads of various quality. But a closer look reveals reasonably well-maintained loops that link up the towns of most interest to travelers. These are also served by buses. The largest of the loops connects Chitré, Las Tablas, Pedasí, Tonosí, and Macaracas (a tiny town whose sole claim to national fame is its Epiphany Festival, held around January 6, during which it stages a reenactment of the gift of the Magis to the baby Jesus). The loop ends back at Chitré.

Carnaval is celebrated throughout the country, but those who can get away try to come to the Azuero during those four days of partying. The Carnaval celebration held in the town of Las Tablas, in southeastern Azuero, is the most famous in the country. For those who don’t mind a madhouse, this is the place to be. Smaller but no less enthusiastic Carnaval celebrations are held in other towns and villages throughout the peninsula.

Another big event is the Festival de Corpus Christi, which takes over the tiny town of La Villa de Los Santos for two weeks between May and July every year. As with Carnaval, specific dates depend on the Catholic religious calendar and vary from year to year. Ostensibly an allegory about the triumph of Christ over evil, it’s most notable for its myriad dances, especially those featuring revelers in fiendishly elaborate devil costumes. Then there’s the Festival Nacional de la Mejorana, Panama’s largest folkloric festival, which takes over the sleepy town of Guararé each September. It draws performers and spectators from around the country.

That’s just for starters. Los Santos alone has more religious festivals than any other province in the country.

Dates for some of these festivals change yearly. ATP, Panama’s ministry of tourism, publishes updated lists of festival dates and details each year. Stop by any of the several ATP offices scattered throughout the Azuero. This is one part of the country ATP does a decent job of covering, especially when it comes to the parties.

It sometimes feels as though the entire peninsula is dedicated to preserving the past, at least symbolically. This includes maintaining the charming but definitely antiquated custom of the junta de embarre (rough translation: the mudding meeting), in which neighbors gather to build a rustic mud home, called a casa de quincha, for newlyweds. Miniature versions of these are sometimes made during folkloric events. Some tradition-minded music festivals go so far as to ban, by town decree, the use of newfangled instruments—such as the six-string classical guitar.

The Azuero Peninsula has an incredibly ancient history. Evidence of an 11,000-year-old fishing settlement, the earliest sign of human habitation in all of Panama, has been found in what is now Parque Nacional Sarigua. Ceramics found around Monagrillo date to at least 2800 b.c., possibly much earlier. It’s the oldest known pottery in all of Latin America.

Excavations at Cerro Juan Díaz, near La Villa de Los Santos, indicate the site was used as a burial and ceremonial ground off and on for 1,800 years, from 200 b.c. until the arrival of the Spanish brought a bloody end to the indigenous civilizations.

Just how complete that victory was can be seen in the modern-day residents of the Azuero. They are by and large the most Spanish-looking people in Panama, with lighter skin and eyes than residents of most other parts of the country.

The Azuero has continued to play an important role in the history of the country into the modern era. On November 10, 1821, for instance, residents of the little town of La Villa de Los Santos wrote a letter to Simón Bolívar asking to join in his revolution against the Spanish. This Primer Grito de la Independencia (First Cry for Independence) is still commemorated today. It was the first step in Panama’s independence from Spain and union with Colombia.

Excerpted from the Fourth Edition of Moon Panama.