Since then, countless Argentine and foreign visitors have benefited from Moreno’s generosity in a reserve that now encompasses a far larger area of glacial lakes and limpid rivers, forested moraines and mountains, and snow-topped Andean peaks that mark the border. So many have done so, in fact, that it’s debatable whether authorities have complied with Moreno’s wish that “the current features of their perimeter not be altered, and that there be no additional constructions other than those that facilitate the comforts of the cultured visitor.

Prior to the “Conquest of the Desert,” Araucanian peoples freely crossed the Andes via the Paso de los Vuriloches south of 3,554-meter Cerro Tronador. The pass lent its name to Bariloche, which, a century since its 1903 founding, has morphed from lakeside hamlet to a sprawling city whose wastes imperil the air, water, and surrounding woodlands.

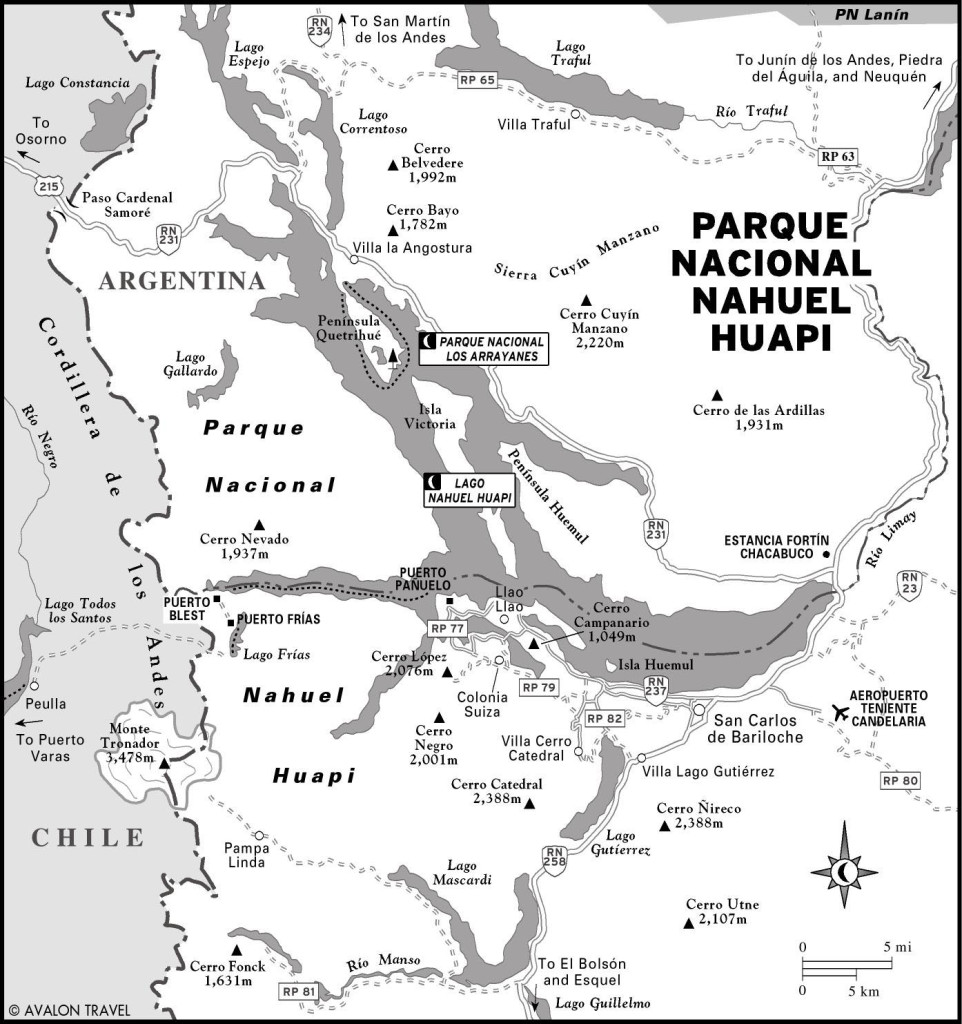

Parque Nacional Nahuel Huapi

For all that, Nahuel Huapi remains a beauty spot that connects two countries via a series of scenic roads and waterways. In 1979, Argentine and Chilean military dictatorships fortified the borders and mined the approaches because of a territorial dispute elsewhere. But a papal intervention cleared the air and perhaps reflected Moreno’s aspirations:This land of beauty in the Andes is home to a colossal peak shared by two nations: Monte Tronador unites both of them…. Together, they could rest and share ideas there; they could find solutions to problems unsolved by diplomacy. Visitors from around the world would mingle and share with one another at this international crossroads.

Now stretching from the northerly Lago Queñi, west of San Martín de los Andes, to the southerly Río Manso, midway between Bariloche and El Bolsón, the park covers 717,000 hectares in southwestern Neuquén and western Río Negro. Together with Parque Nacional Lanín to the north, it forms an uninterrupted stretch well over a million hectares, but part of that is a reserva nacional that permits commercial development. At the park’s western edge, Tronador is the highest of a phalanx of snow-covered border peaks.

Nahuel Huapi’s focal point is its namesake lake, whose finger-like channels converge near the Llao Llao peninsula to form the main part of its 560-square-kilometer surface. With a maximum depth of 454 meters, it drains eastward into the Río Limay, a Río Negro tributary.

In the middle of Nahuel Huapi’s northern arm, Isla Victoria once housed the APN’s park ranger school (now at Córdoba), which trained rangers from throughout the Americas. From Puerto Pañuelo, Turisur’s Modesta Victoria (Mitre 219, tel. 0294/4426109, US$47 plus US$8 national park admission fee) sails once a day to the island, while the Cau Cau (Mitre 139, tel. 0294/4431372, US$47 plus national park admission fee) goes twice. Both continue to Parque Nacional Los Arrayanes (which is more accessible from Villa La Angostura, on the north shore).

The focus of the park is beautiful Lago Nahuel Huapi. Photo © Brian Stacey, licensed Creative Commons Attribution

The Circuito Chico is the most popular way to explore the national park from Bariloche. Following the route takes about a day. There are several possible hikes along the way, as well as spots where you night want to linger, depending upon your interest and the amount of time you have. The roughly 45-kilometer excursion leads west out Avenida Bustillo to Península Llao Llao and returns via the hamlet of Colonia Suiza, at the foot of Cerro López, which makes a good stop for lunch. It’s easily accessible by car, bicycle, or public transportation. Public buses will pick up and drop off passengers almost anywhere along the route. Many Bariloche agencies offer the Circuito Chico as a half-day tour (about US$20 pp), but it’s cheaper to use public transportation.

For exceptional panoramas of Nahuel Huapi and surroundings, take the chairlift Aerosilla Campanario (Av. Bustillo Km 17.5, tel. 0294/4427274, 9am-6:30pm daily, US$11 pp) to the 1,050-meter summit of Cerro Campanario. There’s a restaurant at the summit.

The bus-boat Cruce Andino trip to Chile starts at Puerto Pañuelo, but excursions to Isla Victoria and Parque Nacional Los Arrayanes (across the lake) also leave from here. The outstanding cultural landmark is the Llao Llao Hotel & Resort (Av. Bustillo Km 25, tel. 0810/2225526), a Bustillo creation opened to nonguests for Wednesday’s guided tours (free of charge, previous booking required).

Almost immediately west of Puerto Pañuelo, a level footpath from the parking area leads southwest to an arrayán forest in Parque Municipal Llao Llao; the trail rejoins with the paved road near Lago Escondido. The road itself passes a trailhead for Cerro Llao Llao, a short but stiff climb offering fine panoramas of Nahuel Huapi and the Andean crest. On the descent, the trail joins a gravel road that rejoins the paved road from Puerto Pañuelo, which leads south before looping northeast toward Bariloche. A gravel alternative heads east to Colonia Suiza, known for its Sunday crafts fair (which also occurs on Wednesday in summer). There’s a spectacular assortment of foods available, including sweets, desserts, and curanto (a mixture of beef, lamb, pork, chicken, sausage, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and other vegetables, baked on heated earth-covered stones). The curanto requires reservations, which can be made at Abuela Goye shops or by phoning tel. 0294/4448605.

On any day, try the regional menu at Fundo Colonia Suiza (tel. 0294/4448619, noon-8pm daily in summer, noon-7pm daily the rest of the year, US$12). The individual tabla of smoked venison, pork, trout, salami, and cheese is an unusual but welcome practice (most restaurants have a two-person minimum).

From Colonia Suiza, a zigzag dirt road suitable for four-wheel-drive vehicles and mountain bikes climbs toward Refugio López (tel. 0294/15-4580321, open mid-Dec.-late Mar., US$16 pp with kitchen use), 1,620 meters above sea level. Farther west and near the junction of the paved and gravel roads, a steep footpath climbs 2.5 hours to Refugio López.

From Refugio López (a good place to take a break and a beer), the route climbs to Pico Turista, a strenuous scramble over rugged volcanic terrain. With an early start, experienced hikers will possibly reach the 2,076-meter summit of Cerro López.

From Bariloche’s Barrio Belgrano, Avenida de los Pioneros intersects a gravel road that climbs gently and then steeply west to Cerro Otto’s 1,405-meter summit. While it’s a feasible eight-kilometer hike or mountain-bike ride, it’s easier via the gondolas of Teleférico Cerro Otto (Av. de los Pioneros Km 5, tel. 0294/4441035, 10am-6:30pm daily, US$16 pp, US$10 for seniors and for children 6-12). A free transfer from downtown’s ticket office at Avenida San Martín and Independencia is included.

On the summit road, at 1,240 meters, the Club Andino’s Refugio Berghof (tel. 0294/15-4271527) serves meals and drinks. Its Museo de Montaña Otto Meiling honors a pioneering Andeanist who built his residence here.

Cerro Catedral’s 2,388-meter summit overlooks Villa Catedral, the ski village that serves Catedral Alta Patagonia, the area’s major winter-sports resort. From Villa Catedral, the chairlifts Telesilla Princesa I, II, and III (9:30am-4:45pm daily, US$19 pp, US$12 for children) carry visitors to Confitería Punta Princesa. Hikers can continue along the ridgetop to the Club Andino’s 40-bed Refugio Emilio Frey (tel. 0294/15- 4352222, US$12.50 pp), 1,700 meters above sea level and open all year. The spire-like summits nearby are a magnet for rock climbers.

Its inner fire died long ago, but Tronador’s ice-clad volcanic summit still merits its name (the “Thunderer”) when frozen blocks plunge off its face into the valley below. The peak that surveyor Bailey Willis called “majestic in savage ruggedness” has impressed everyone from Jesuit explorer Miguel de Olivares to Perito Moreno, Theodore Roosevelt, and the hordes that view it every summer. Its ascent, though, is for skilled snow-and-ice climbers only.

Monte Tronador. Photo © Robert Cutts, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

Source of the Río Manso, Tronador’s icy eastern face gives birth to the Ventisquero Negro (Black Glacier), a jumble of ice, sand, and rocky detritus, and countless waterfalls. At Pampa Linda, at the end of the Lago Mascardi road, whistle-blowing rangers prevent hikers from getting too close to the Garganta del Diablo, the area’s largest accessible waterfall.

From Pampa Linda, hikers on a two-day trek (requiring access to Chile) can visit Club Andino’s basic Refugio Viejo Tronador via a trail on the road’s south side. Refugio Viejo Tronador is a kiln-shaped structure that sleeps a maximum of 10 climbers in bivouac conditions. Information is available at Club Andino (20 de Febrero 30, tel. 0294/4527966) in Bariloche. On the north side, another trail leads to the 60-bed Refugio Otto Meiling (tel. 0294/15- 4213921, US$19 pp), 2,000 meters above sea level. Between early January and March, well-equipped backpackers can continue north to Laguna Frías via the 1,335-meter Paso de las Nubes and return to Bariloche on the previously booked bus-boat shuttle via Puerto Blest and Puerto Pañuelo.

Reaching the Tronador area requires a roundabout drive via southbound RN 40 to Lago Mascardi’s south end, where westbound RP 81 follows the lake’s southern shore. At kilometer 9, a northbound lateral crosses Río Manso and becomes a single-lane dirt road to Pampa Linda and Tronador’s base. Because it’s narrow, morning traffic is one-way inbound (10:30am-2pm), afternoon traffic is outbound (4pm-6pm), and at other times the road is open to cautious two-way traffic (7:30pm- 9am). From December to Easter holidays, Active Patagonia (tel. 0294/4529875) provides transportation from Club Andino’s Bariloche headquarters to Pampa Linda at 8:30am daily, returning at 5pm (reservations required, US$38 round- trip, two hours.

For detailed park information and hiking registration, contact the APN (San Martín 24, tel. 0294/4423111) or Club Andino Bariloche (20 de Febrero 30, tel. 0294/4527966). The shelters are also good sources of information within the park.

Before starting any hike in the park and within 48 hours prior to the date of the hike, a free form provided at APN’s offices (also available online on the park’s webpage) and at Club Andino must be filled in to keep a record at the national park’s Registro de Trekking and to show upon park rangers’ request.

Club Andino’s improved trail map, Refugios, Sendas y Picadas, at a scale of 1:100,000 with more detailed versions covering smaller areas at a scale of 1:50,000, is a worthwhile acquisition. Aoneker publishes more sophisticated versions of some areas. The fifth edition of Tim Burford’s Chile and Argentina: The Bradt Trekking Guide (Chalfont St. Peter, United Kingdom: Bradt Travel Guides, 2001) covers several trails in detail, but its maps are suitable for orientation only.

Excerpted from the Fourth Edition of Moon Patagonia.