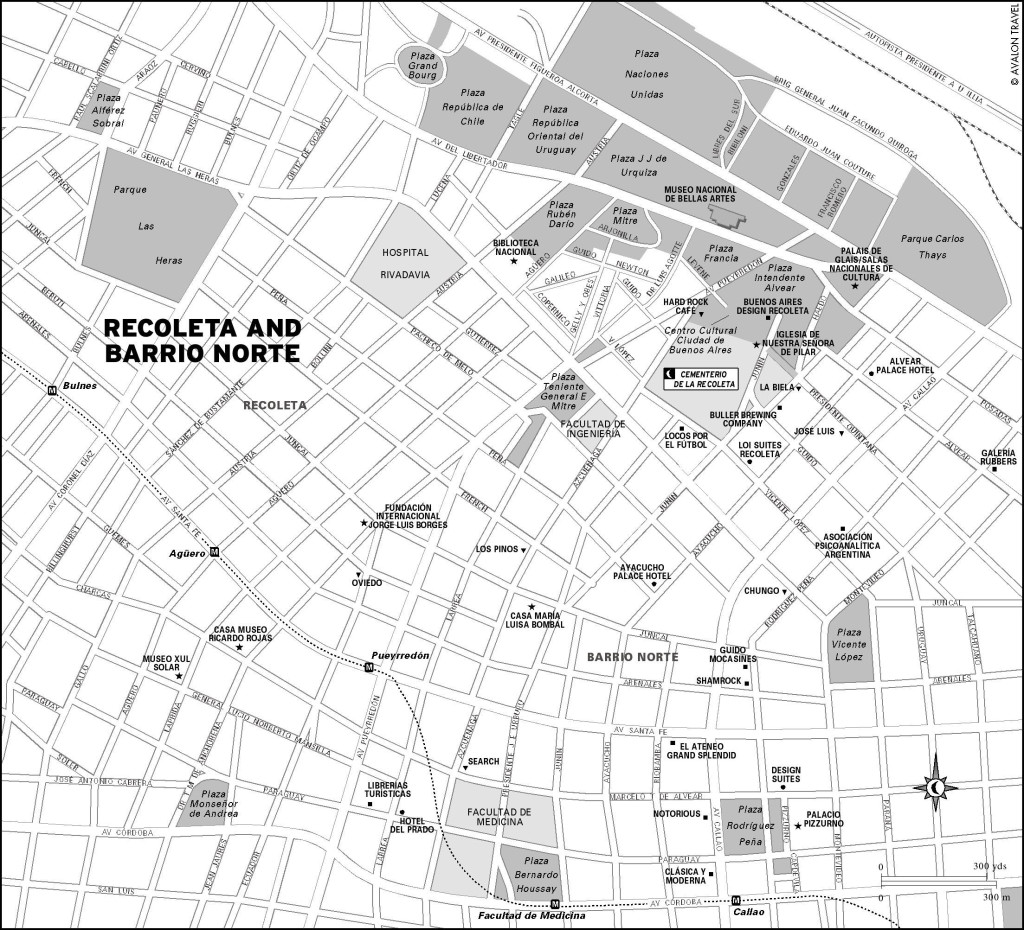

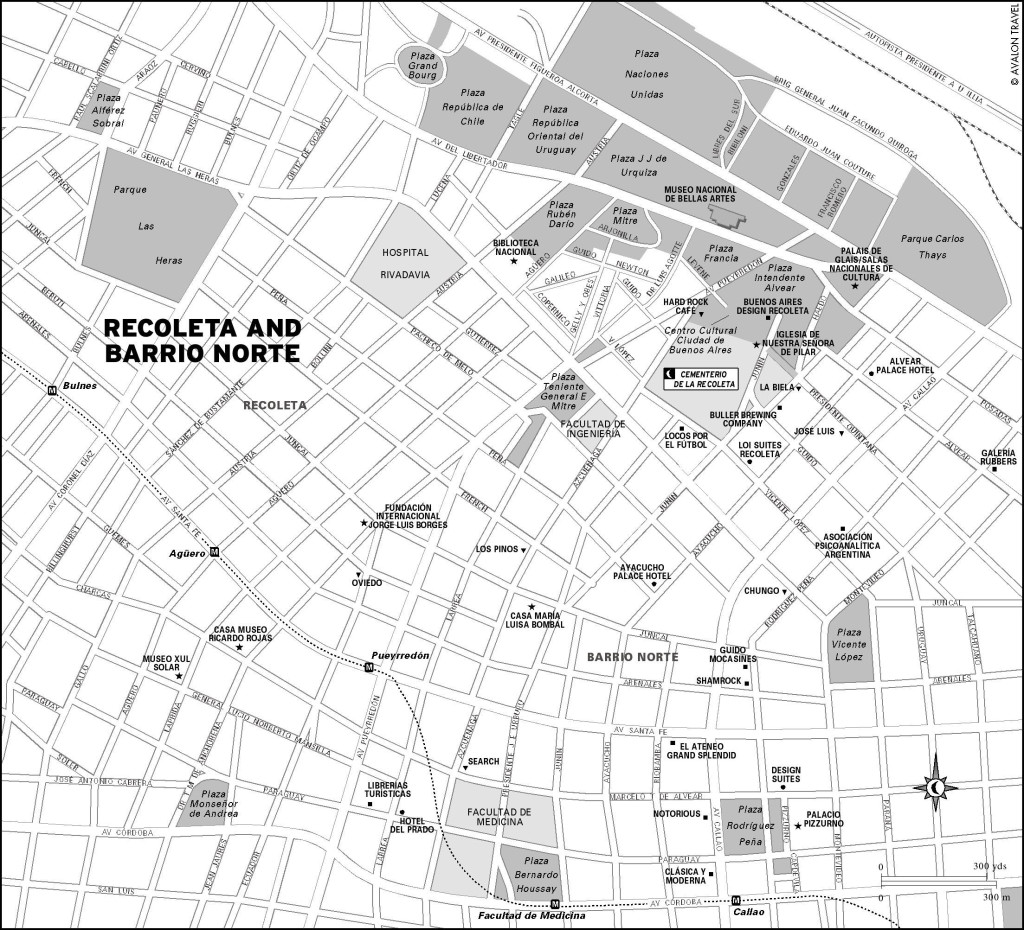

Once a bucolic outlier, Recoleta urbanized rapidly when upper-class Porteños fled San Telmo after the 1870s yellow fever outbreaks. It’s internationally known for the Cementerio de la Recoleta (Recoleta Cemetery, 1822), whose elaborate crypts and mausoleums cost more than many—if not most—Porteño houses. Flanking it is the Jesuit-built Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de Pilar (1732), a baroque church.

Arguably, Recoleta cemetery is even more exclusive than the neighborhood. Photo © Kevin Jones, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

Bordering the church and cemetery are sizable green spaces, including Plaza Intendente Alvear and Plaza Francia, frequented by street performers and a legion of paseaperros (professional dog walkers). On the southeastern corner, along Robert M. Ortiz, are some of Buenos Aires’s most traditional cafés, most notably La Biela (Av. Quintana 596/600, tel. 011/4804-0449).

Alongside the church, the Centro Cultural Ciudad de Buenos Aires (Junín 1930, tel. 011/4803-1040, 2pm-9pm Tues.-Fri., noon-9pm Sat.-Sun. and holidays, free except for some areas) is one of the capital’s most important cultural centers.

Facing Plaza Francia, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (1933) is the national fine-arts museum. Several other plazas stretch along Avenida del Libertador, northwest of the museum toward Palermo.

For quick and dead alike, Cementerio de la Recoleta (Junín 1790, tel. 011/4803-1594, 7am-6pm daily, free) is Buenos Aires’s most prestigious address; its roster of postmortem residents represents wealth and power as surely as the inhabitants of surrounding Francophile mansions and luxury apartments hoard their assets in overseas bank accounts. Socially, the cemetery is more exclusive than the neighborhood—cash can buy an impressive residence, but not a surname like Alvear, Anchorena, Mitre, Pueyrredón, or Sarmiento.

Its top attraction, though, is the crypt of Eva Perón, whose relentless ambition overcame humble origins and brought her to the pinnacle of power with her husband, General and President Juan Perón, before her death in 1952. Even Juan Perón, who lived until 1974, failed to qualify for Recoleta.

Recoleta and Barrio Norte

There were other ways into Recoleta, though. One unlikely occupant is boxer Luis Angel Firpo (1894-1960), the “wild bull of the Pampas,” who nearly beat Jack Dempsey for the world heavyweight championship in 1923. Firpo, though, had pull—his sponsor was landowner Félix Bunge, whose family owns some of the cemetery’s most ornate constructions.

The Cementerio de la Recoleta is the site for many guided on-demand tours through travel agencies; the municipal tourist office sponsors occasional free weekend tours.

The Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (Av. del Libertador 1473, tel. 011/4803- 0802, 12:30pm-8:30pm Tues.-Fri., 9:30am-8:30pm Sat.-Sun., free) mixes works of well-known European artists such as Picasso and Van Gogh with Argentine counterparts, including Antonio Berni, Cándido López, Benito Quinquela Martín, Prilidiano Pueyrredón, and Lino Spilimbergo. In total, Argentina’s traditional fine-arts museum houses about 11,000 oils, watercolors, sketches, engravings, tapestries, and sculptures. Among the most interesting works are López’s detailed oils, which recreate the history of the Paraguayan war (1864- 1870) despite his having lost his right arm to a grenade.

The Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes offers guided tours of occasional special exhibits, for a small charge.

Excerpted from the Fourth Edition of Moon Patagonia.