Money is everyone’s concern, especially when traveling overseas. Getting accustomed to foreign currency, knowing where and when to change it, and calculating what things cost can be challenge even when it’s a country you know well. Governments have their own issues, which may be why Chile has recently introduced a new series of hard-to-falsify banknotes that, simultaneously, help promote the country’s attractions.

Money is everyone’s concern, especially when traveling overseas. Getting accustomed to foreign currency, knowing where and when to change it, and calculating what things cost can be challenge even when it’s a country you know well. Governments have their own issues, which may be why Chile has recently introduced a new series of hard-to-falsify banknotes that, simultaneously, help promote the country’s attractions.

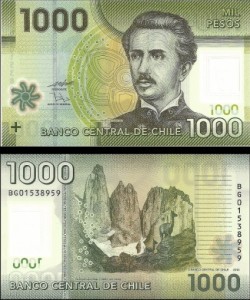

For example, the new 1000-peso note (pictured above) features a portrait of Ignacio Carrera Pinto, a 19th-century war hero, on its face, but the back of the note shows the granite pinnacles of Torres del Paine. The notes don’t occupy much wallet space, as they’re only about three-quarters the size of a dollar bill but, more interestingly, they have a small transparent insert that duplicates the portrait on the front. Presumably this is a security measure, to deter counterfeiting.

One of the pitfalls of guidebook research and publishing is the unpredictability of exchange rates.One of the pitfalls of guidebook research and publishing is the unpredictability of exchange rates. In all my Moon Handbooks, I use the US dollar as a baseline currency, because it’s so widely accepted throughout the Southern Cone, but that has its drawbacks. When I researched the third edition of Chile, three years ago, the peso traded at about 600 to the dollar, even spiking up to 650, but for most of my recent two-months-plus in the country, the rate hovered around 480. Despite Chile’s low inflation rates, the country had grown significantly more expensive in dollar terms, and the new edition – due out at year’s end – will reflect that.Since I returned to California three weeks ago, though, the dollar has climbed above 500 once again, but that’s the rate I had already decided to use as a baseline for the upcoming edition. Still, it emphasizes the need to pay attention to exchange rates even if, in general, relative prices stay the same. The most basic accommodations remain the cheapest, the most elaborate restaurants the most expensive, and so it goes.

Relative prices remain the same in Argentina, but the dynamics of the economy are less predictable. The official exchange rate is barely creeping up, at around 4.5 to the dollar, but independent economists calculate an annual inflation rate of roughly 25 percent, about triple what the government admits. At the same time, foreign exchange controls have stimulated a black market on which the dollar is trading at roughly 5.5 pesos.

That breach between the official and informal dollar, which is regularly reported on the front page of Buenos Aires dailies, suggests the government’s measures – including the deployment of 300 dollar-sniffing golden retrievers – have been less effective than it had hoped. The state-run TV network Visión Siete is running what is clearly a propaganda spot that shows the dogs at work.

It’s recently sent AFIP tax agents into the street to apprehend the street changers known colloquially as arbolitos (so-called because, like trees, they’re planted in one spot), but that’s had only minimal effect in a country where outwitting officialdom is the national sport. Former central bank president Martín Redrado, fired by President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in 2010, says the government’s restrictions are an unsustainable “dead-end street (Redrado, for what it’s worth, had been appointed by Fernández’s late husband Néstor Kirchner).

It’s risky, meanwhile, for foreigners to tread in the black market. Unless you’re dealing with a trusted friend, changing dollars for pesos is inadvisable. For the government, though, the best remaining alternative might be importing Dutch boys to plug the dikes.