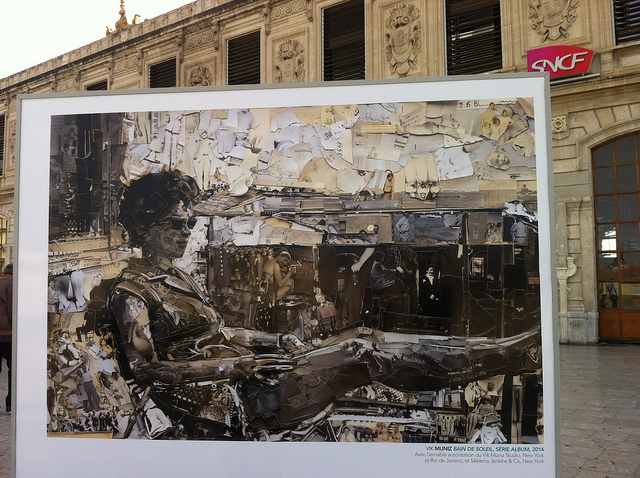

A Vik Muniz print on display in front of the St. Charles train station in Marseille. Photo © Jeanne Menj, licensed Creative Commons Attribution No-Derivatives.

Earlier this week, I went with a friend of mine to see Waste Land, a fascinating documentary that won the World Cinema Audience Award at last year’s Sundance Film Festival and is now competing as a contender for Best Documentary at next Sunday’s Oscar ceremony.

A British-Brazilian co-production, Waste Land begins in the Brooklyn studio of Brazil’s most celebrated contemporary artist, Vik Muniz. Born in 1961, Muniz grew up in a poor suburb of São Paulo, but won a scholarship to art school and had begun a career in advertising when he was shot in the leg trying to break up a fight. With the money he received as compensation, in the early ‘80s, he decided to make a big leap: to New York City. After dabbling in sculpture, he entered the art world with a splash as a photographer who made reproductions of his own works. His breakthrough series, “Sugar Children”, consisted of snapshots he took of the children of sugar plantation workers on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts; he copied the images by layering sugar on black paper and photographing the results.

In 2008, Muniz initiated one of his most ambitious projects to date – using garbage.Since then, Muniz has made a career out of such visual double-entendres, often riffing on classic works of art such as the “Double Mona Lisa”, in which Da Vinci’s famous muse is rendered in peanut butter and jelly, and “The Last Supper”, with Christ and the apostles depicted in chocolate syrup. Other materials that he has used in the composition of his images include string, toy soldiers, dirt and diamonds.

In 2008, Muniz initiated one of his most ambitious projects to date – using garbage. This two-year undertaking became the subject matter of Waste Land.

The film begins with Muniz planning a trip to the world’s largest garbage dump, located in a suburban Rio de Janeiro favela known as Jardim Gramacho. As seen through Google Earth and aerial photos, this waste land resembles some post-modern version of hell with people scavenging like insects through mountains of trash. We can totally identify with Muniz’s wife who tosses him dubious looks while bringing up issues of safety and security. However, on the ground, once Muniz and we, the audience, get over ourselves – and our instinctive aversion to the mountains of waste that humans and vultures alike go sifting through in search of sustenance (financial and physical) – we quickly get to know these catadores (garbage pickers) as individuals with personalities that effortlessly draw us in.

There is Tião, the handsome founder and president of the local Associação de Catadores co-op, who refers to himself as “a picker of recyclable materials”. There is also Zumbi, who has educated himself by reading discarded books (such as Machiavelli’s The Prince). Suellem is a teenage mother who has chosen a career of garbage picking over prostitution along the sidewalks of Copacabana. Meanwhile, elderly Irmã sifts through the landfill’s refuse for the freshest leftovers, which she boils into stews that feed the catadores (which number 3,000 on any given day).

After months spent getting to know them and hearing their stories, fueled by the desire “to help people change their lives with the same materials they deal with every day,” Muniz hires some of the catadores to pose for him as figures from classic works of art. Lying in a bathtub overflowing with trash, Tião is photographed as David’s “Marat”. Posing with her two children, Suellem becomes a Rennaissance Madonna. Meanwhile Zumbi is transformed into Millet’s “Sower”. With these images projected onto the floor of a giant studio, the catadores then set to work filling in the contours of their own portraits with garbage they have meticulously gathered themselves. Once the works are complete, Muniz steps in with his camera to photograph the final tableaux.

The film’s climax involves a trip in which Muniz travels to an auction in London in the company of Tião and his portrait. When “Marat (Sebastião)” sells for $50,000, an overwhelmed Tião calls his mother in Rio, weeping. The money is subsequently split among the subjects/co-creators of the works as well as donated to the Associação de Catadores, which is able to invest in a recycling center along with a medical clinic, day care facility, and skills-training program for the catadores.

In 2009, when all portraits are included in a massive retrospective of Muniz’s work that tours major cities in the United States, Canada, Britain, and Brazil (where it broke attendance records), the catadores themselves are on hand for opening night at Rio’s Museu de Arte Moderna. As a catadora confesses to an interviewer: “Sometimes we see ourselves as so small, but people out there see us as so big, so beautiful.”

Aside from being moving (without being maudlin), Waste Land raises a lot of very complex questions about art, poverty, preconceptions, and life, not to mention Brazil. And happily, the film isn’t afraid of shying away from uncomfortable situations.

For instance, when we (and Muniz) first meet and are drawn into the lives of the catadores, they are so singularly charming and “alegre” (a Brazilian cliché that is as deceptive as it is valid) that we are lulled into thinking that, despite their poverty (they earn the equivalent of around $25 a day), they are somehow “happy” with their lives. Of course, all that changes when they spend two weeks away from the landfill, working as artists in Muniz’s studio. Muniz (and perhaps the guilty audience) is shocked to discover that the catadores weren’t so “happy” after all; in fact, none of them want to return to their lives at the dump.

A similar moment occurs when Muniz and his (soon-to-be-ex) wife Janaína Tschäpe (also a Brazilian artist) get into a heated argument over whether it’s cruel or not for Muniz to whisk Tião off to the high-rolling art world of London, knowing that he’ll ultimately have to return to the reality of Jardim Gramacho. Although the question is open to debate, Muniz firmly believes that he is changing his subjects’ lives for the better by “showing them another place,” even if they never make it out of the landfill.

I won’t spoil the ending by telling you what happens to Muniz’s catador colleagues. But it’s interesting to note that last summer, Brazil passed a law to eradicate open dumps and integrate the nation’s catadores into the recycling industry. As it is, public recycling programs in Brazil are virtually non-existent – the reason the country boasts one of the highest recycling rates on the globe is due to the survival-fueled fervor with which catadores meticulously sift through and reclaim the vast majority of the nation’s trash.

* * *

It was twilight when my friend and I emerged from the cinema into Salvador’s bustling Centro. Businesses were closing and stores had piled the curbs high with garbage bags. As we walked down the street in the midst of the rush hour mayhem, a small army of catadores were quietly sifting through the bags, boxes, and trash cans. They were filling gigantic sacks slung over their shoulders, or balanced upon their heads, with beer cans and plastic bottles. Sometimes they stumbled upon some edible sustenance and stopped for a quick bite.

For a moment, we were shocked to see that the world of Waste Land had come to life right in front of us. Of course, the sensation didn’t last; we kept walking, and it quickly just became part of another normal day.