For the most part, these films take a collage approach, tightly (or loosely) interweaving rare period interview footage and performances with archive photos and contemporary interviews with partners and colleagues from Brazil’s artistic milieu. The best of them firmly place these musical figures in the artistic, social, and political context of their time. They not only capture some essence of their talented subjects, and make the case for their inclusion in Brazil’s daunting musical pantheon, but they are also able to conjure up and shine a revealing light upon complex moment(s) in Brazilian history.

What’s most amazing about Dzi Croquettes is that they managed to create such an impact (especially in Rio de Janeiro ) during the most oppressive years of the military regime in which censorship, arrest, and torture of artists who crossed the line of acceptability was common.One such documentary I recently saw that achieved this marvelously was Dzi Croquettes. Unlike many of the household names alluded to above, Dzi Croquettes—who, strictly speaking, were more a cabaret act than a musical group – are all but forgotten today. However, in the 1970s, this irreverent group of 13 stray and talented actor-dancers became the unlikely voice of the Brazilian counter-culture; they revolutionized Brazilian theater while exploding notions of sexual identity.Amidst the darkest days of Brazil’s military dictatorship (1962-1985), Dzi Croquettes became a subversive sensation with shows that creatively mingled cabaret-style music and dance with monologues and comic sketches into an unusual hybrid. The clincher was the fact that all 13 Dzi Croquettes appeared in tottering heels and skimpy G-strings, accessorized with Carmen Miranda-worthy make-up and lashes and enough glitter to sink a ship. And yet, this was no drag show; the men all proudly flaunted their beards, hairy chests and legs, and sinuous yet masculine bodies. As one member famously quoted at the time: “We’re not men. We’re not women. We’re people.” (Although all of the Dzi Croquettes were irrepressibly gay, they were hardly flag-wavers).

What’s most amazing about Dzi Croquettes is that they managed to create such an impact (especially in Rio de Janeiro ) during the most oppressive years of the military regime in which censorship, arrest, and torture of artists who crossed the line of acceptability was common. Although their ethos and aesthetic was derived from Rio’s Carnaval tradition of men dressing as women, their heady blend of bawdiness and gracefulness, while inimitably Brazilian, was also very vanguard as was their daring androgyny. Amazingly, government censors – never very good at reading between the lines – let them strut their stuff until 1973, when the Dzi Croquette phenomenon had become such that mobs were lining up for blocks to see their nightly shows in Rio – at which point they were shut down.

Instead of giving up, Dzi Croquettes did what any resourceful cross-dressing cabaret troupe would do: they up and went to Paris. Initially, Parisian audiences and critics alike hated them. But a fairy godmother by the name of Liza Minnelli stepped in to save the day. Minnelli (who is featured prominently in the documentary) was a great pal and admirer of founding Croquette Lennie Dale, an American dancer whom, living in New York in the 1950s, “had so much talent that Broadway didn’t know what to do with it.” However, Rio – where Dale emigrated in the early ‘60s – did. Dale – the first to create choreographies to the new sound known as bossa nova – was the driving force behind Dzi Croquettes. A Bob Fosse-style perfectionist with a larger than life personality, Dale was responsible for the group’s professionalism and polish as well as its top-notch dance performances.

The only live record that exists of the group is courtesy of a German film crew, who hearing something revolutionary was afoot in Paris, came and taped one of their shows and then forgot about the footage for 35 years.Anyway, back to Paris and Liza Minelli who, at an after-party for her own show, insisted on dragging all her guests (among them Catherine Deneuve, Mick Jagger, Josephine Baker, and the designer Valentino) to a midnight performance of Dzi Croquettes’ revue. As a result of Liza’s wand-waving, Dzi Croquettes became an overnight phenomenon; they spent much of the next two years playing the prestigious Le Palace to dizzying critical and popular acclaim.The documentary traces all of this history, interweaving historical footage with clips of talking heads (aside from Minnelli, musicians Gilberto Gil and Ney Matogrosso are probably the most recognizable to foreign audiences) and performance footage. Frustratingly, the latter is limited, and often of poor quality, due to the fact that the military dictatorship prevented the filming of anything deemed to be subversive. The only live record that exists of the group is courtesy of a German film crew, who hearing something revolutionary was afoot in Paris, came and taped one of their shows and then forgot about the footage for 35 years.

Quality issues aside, the performance scenes capture the spirit of Dzi Croquettes: their unique vitality, charm, and disarming sensuality that mixes elements of masculinity and femininity. It also briefly delves into the personalities of each “family member”- and for a while that’s what Dzi Croquettes were: family. In Brazil and in Europe, they all lived together in one communal house in which sex-and-drug-fueled bacchanalia was kept more or less in check by a wry and affectionate black den mother, who was also the closest thing the Dzi Croquettes ever had to a manager.

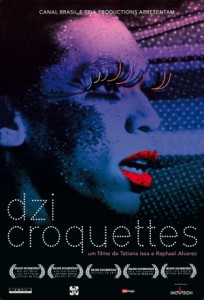

Produced by Canal Brasil and TRIA Productions.

With so many disparate personalities in play, it was little wonder that the family broke up. This occurred in 1975 when, suffering from homesickness, some members insisted upon returning to Brazil at the behest of a rich Bahian landowner who wanted the group to give a private performance on his ranch. Internal fighting resulted in Lenny Dale quitting the group, which left the remaining Dzi Croquettes splintered. And they never recovered. During the ‘80s and ‘90s, four members of the group (including Dale) died of AIDS – and another three were shockingly murdered.

Dzi Croquettes is directed by two Brazilians living in New York, Tatiana Issa and Raphael Alvarez, and what gives it an extra edge is that it’s clearly a labor of love: Issa’s father, who also died an early death due to AIDS, was a lighting technician for the Dzi Croquettes and some of Tatiana’s earliest memories involved being surrounded by “all these amazing men dressed as women who weren’t transvestites.”

Issa’s narrative voice is present in the film, but perhaps one of the most surprising – and telling – elements of this film occurred behind-the-scenes. When Issa and Alvarez tried to get funding, they were shocked at their inability to attract Brazilian investors to a project that was all about rescuing an important part of the country’s cultural history. Ultimately, the duo – who both work day jobs – succeeded in raising the necessary funds in the U.S.

As tragic as the deaths of so many of the Dzi Croquettes is the fact that the memory of their existence has already come so close to fading away. In terms of the lives lost, Issa gives a fittingly lyrical elegy, quoting a popular Brazilan expression; “Bicha não morre, vira purpurina” (Gays don’t die, they become glitter”). In terms of their legacy, the film itself ensures that it will not be forgotten.