Photo © Michael Sommers.

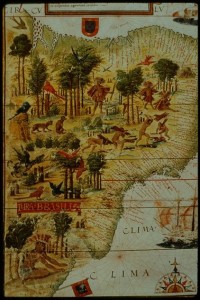

Turns out that the myth about El Dorado, the lost city in the midst of the Amazon rainforest, peopled by an advanced civilization, is not so much of myth after all.Ever since the 16th century, when Spanish explorer Francisco de Orellana navigated his way down the length of the Amazon River in search of the legendary city of gold and riches, countless adventurers (both real and armchair) have been inspired by the idea of a lost civilization hidden away in the jungle. Many have been inflamed by historic first-hand accounts such as that of Spanish chronicler Gaspar de Carvajal, the Spanish friar who accompanied the Orellana expedition, and who wrote about “cities that gleamed white,” “fine highways,” and “very fruitful land.”

Then along came 20th-century scientists, who ruined all the fun by arguing that the only type of civilization that could survive the “Green Hell” of the rainforest would be small groups of nomadic hunters and gatherers. For a long time, their version held sway. However, new discoveries by archaeologists are proving that the original seekers of El Dorado may not have been so wrong after all.

The notion of advanced indigenous societies in the Amazon was first brought to light in the 1980s by American archaeologist Anna C. Roosevelt.The notion of advanced indigenous societies in the Amazon was first brought to light in the 1980s by American archaeologist Anna C. Roosevelt (great granddaughter of President Theodore Roosevelt, who had embarked on his own Amazonian adventure in 1914 – documented in his page-turner Through the Brazilian Wilderness).

Anna Roosevelt had uncovered the presence of housing foundations, advanced agriculture, and highly elaborate ceramic pottery on the Ilha de Marajó, a Switzerland-sized island sitting in the mouth of the Amazon (and today known for its beaches and buffalo farms). Her research led her to believe that an indigenous society whose population numbered 100,000 – that created a distinctive Marajoana culture – inhabited the island.

More recently, other finds have supported Roosevelt’s originally radical, and still controversial, thesis of advanced Amazonian societies whose apogee was in the years 800-1500 A.D. In the Xingu delta, scientists have uncovered traces of man-made moats and canals as well as roads and planned villages with houses. In the region surrounding Manaus, traces of orchards (planted with semi-domestic fruits such as jungle avocados and sapotis) have been found along with “terra preta” rich “black” and highly fertile earth that indigenous people made by mixing charcoal, human waste, and other organic materials.

All the evidence – much of which is gleaned with the aid of technology such as satellite imagery, ground penetrating radar and remote sensors – indicates that Amazonian inhabitants were not only sedentary, but thriving due to sophisticated engineering techniques that, according to some scientists, rivaled those of the pyramid-building Egyptians. It’s estimated that at the height of this civilization the Amazon may have sheltered more than 20 million people.

Tragically, the most ardent and enthusiastic believers of El Dorado – the conquistadores – were also at least partially responsible for its demise. Upon contact with Europeans, these civilizations rapidly disintegrated, victims of disease to which they had no natural resistance. However, as Roosevelt, today a professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois, recently told a reporter for the The Washington Post, these Amazonian cultures were extremely sophisticated. Says Roosevelt: “They have magnitude, they have complexity. They are amazing.”