Photo © Michael Sommers.

The other day, my mother sent me an e-mail entitled “fluden!!!”, in which she declared, triumphantly, that she had succeeded in tracking down a recipe for the perfect Passover dessert. For those of you who haven’t a clue what it is, fluden is a traditional Jewish sweet (also known as fladen and floden, depending on one’s Yiddish dialect) featuring layers of fruits and nuts wrapped in wafer-thin pastry. Interestingly, you’d be hard-pressed to find fluden in North America; even in the most diehard Jewish kitchens, it’s somewhat of a rarity. In fact, my mother (the daughter of Lithuanian Jews whose father studied to be a rabbi and whose mother was a hard-core baker) had never heard of, let alone tasted, fluden until last year when she and I traveled to Recife, capital of Pernambuco.

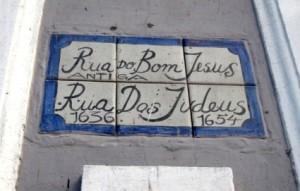

Northeastern Brazil might be the last place you’d expect to encounter Jewish pastries, but we discovered delicately wrapped, small chunks of fluden on sale at a tiny gift store that was located inside Recife’s Sinagoga Kahal Zur Israel. Dating back to the 1530s, Kahal Zur Israel (the Rock of Israel) was the first synagogue built in the New World. Back then, Rua do Bom Jesus – one of the main streets running through the historic city center that is known today as Recife Antigo – was referred to as Rua dos Judeus (Street of the Jews) owing to the fact that this bustling street, and those around it, were home to a small but thriving Jewish community.

Like most overseas traditions that wash up on Brazilian shores, fluden has suffered some “Brazilian” adaptations.Although Jews were present in Brazil right from the beginning – headed by explorer Pedro Alvares Cabral, the Portuguese expedition of “discovery” that landed off the southern coast of Bahia, in 1500, included a Polish-born Jew as an interpreter along with some mapmakers and astronomers of possible Jewish origin – the first Jews who immigrated to Brazil did so covertly. Known as marranos, or New Christians, these Portuguese and Spanish Jews converted to Christianity in order to evade the wrath of the Inquisition. Even those who fled to Brazil in the 1500s, continued to cautiously observe certain rituals under the guise of Catholicism.

However, things changed in 1630 when, seduced by the thriving sugar plantations of Northeastern Brazil, the Dutch seized the fledging colony of Pernambuco from the Portuguese. Their promotion of religious tolerance soon had Jews from Iberia and Amsterdam, as well as other parts of Brazil flocking to the new Dutch colony’s capital of Maurtizstad (later rechristened Recife). During the quarter century of Dutch occupation that ensued, Recife’s Jewish community grew to an estimated 1,400 people. Representing one-tenth of the city’s population (and one-half of all free white citizens), these Jewish newcomers played a major role in the city’s early development.

When the Portuguese finally ousted the Dutch from Pernambuco in 1654, the Jewish heyday in colonial Brazil came to an end. Recife’s Jews scattered. Some moved into the Interior where they were once again forced to camouflage their religious practices. (Amazingly, to this day, there are families in the deepest Sertão who are still in possession of menorahs that have been passed down through generation while others have incorporated vestiges of Sephardic traditions into family rituals.) Others scattered throughout the Diaspora. The most famous of these fugitives were a group of 23 Recife Jews who set sail for Amsterdam, only to be captured by Spanish pirates. Luckily, a passing French ship rescued them and dropped them off at another Dutch colony by the name of Nieuw Amsterdam; and thus was born New York’s first Jewish community.

Meanwhile, back in Recife, the Kahal Zur Israel synagogue was abandoned and forgotten until excavations in the 1990s uncovered the mikve, a ritual fountain used for purification. After undergoing restoration and major renovations, it reopened as a Jewish cultural center and museum that traces the history of Jews in Pernambuco.

Indeed, there was a second act for Jews in Recife. In the 1920s, fleeing persecution and pogroms, a new wave of Ashkenazi Jews from Russia once again found refuge in this tropical port city. And this is where the fluden enters the story since this classic Jewish recipe migrated along with them. Like most overseas traditions that wash up on Brazilian shores, fluden has suffered some “Brazilian” adaptations. In fact, in Recife, it’s not uncommon to find versions with pastry made of cashew nut matzoh meal and fillings composed of guava jelly (see attached recipe).

This week is Passover and my mother was hoping to make the Pernambucano version of fluden for the seder to which she’s been in invited in Toronto. However, seeing as guava and cashews aren’t as easy to come by in Canada as they are in Brazil, she’s going to do some substituting of her own and make hers using wild blueberries, cranberries, and almonds. Feliz Pesach, and Viva a Diaspora!