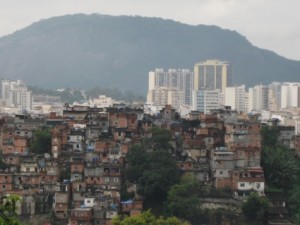

Photo © Michael Sommers.

Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva is the latest to endorse the growing phenomenon of Rio’s “ favela tourism” – a trend that has generated lots of debate (the concept of “touring” favelas has both fierce proponents and critics) and which I explore at some length in Moon Rio and the Rio chapter of Moon Brazil. Lula made the endorsement in a speech he gave at the opening of the Fifth World Urban Forum on March 22. Organized by UN-Habitat and the Brazilian government, the week-long event brought together government representatives, community organizers, diplomats and academics to discuss the alarming fact that one in three of the world’s urban dwellers is also a slum dweller (i.e. a person living in overcrowded conditions in precarious structures, without access to water or sanitation).In his opening remarks, Lula invited participants to visit the favelas of Rio to see for themselves the public investments that are being made in terms of urban infrastructure. Although he suggested going in organized visits made in collective cars or vans (which is how most favela tours are conducted), he also warned: “Don’t go wandering off into areas you don’t know – stay in the normal (italics are mine) areas and nothing will happen.”

While it’s true, as the President claimed, that these government efforts at improving favela life are “historic,” it’s equally true that there isn’t much point of comparison; prior to the 21st century, favelas rarely received acknowledgment let alone investments. However, after years of unsuccessfully trying to pretend that they didn’t exist (until recently, city maps of Rio de Janeiro represented areas occupied by favelas as blank space), governments are changing tactics and trying to integrate favelas and their dwellers into the fabric of city life.

For now, at least, favelas are an integral part of urban Brazilian life. Whether or not you decide to “tour” one is a personal decision, but you’ll inevitably come into contact with them – even if you’re only driving by. In Rio, where favela violence, involving drug cartels and police, routinely terrorizes residents and spills over into the city’s wealthier neighborhoods, efforts at curtailing crime and improving safety and infrastructure by the state and municipal governments have been ramped up – fueled in part by the knowledge that in 2014 (for the World Cup) and 2016 (the Summer Olympics) the eyes of all the world will be on Rio.According to the UN’s State of the World’s Cities 2010/2011 Report released last week, Brazil has actually seen some positive results in terms of reducing the so-called urban divide. After China, India, and Indonesia, Brazil ranked fourth in countries in which the percentage of the population living in slums diminished over the last decade.

However, Brazil is a country in which paradoxes rule. To wit: in terms of Latin America, Brazil had the largest number of people – 10.4 million – who stopped living in favela conditions (which doesn’t necessarily mean they leave the favela itself). However, only 16 % of Brazilians saw their living conditions improve compared to 40.7 % in Argentina, 39.7 % in Colombia, 27.6 % in Mexico, and 21.9 % in Peru.

According to the UN report, over the last ten years, the percentage of Brazilians living in favelas decreased from 31.5 percent to 26.4 percent. These encouraging results are the consequence of declining birth rates combined with new economic and social policies. Lula’s government saw the creation of a Ministry of Cities (created in 2003) dedicated to the improvement of urban life, as well as the adoption of a constitutional amendment guaranteeing all citizens the right to a home, and the development of programs that subsidize the purchase of land, construction materials and services. However, since the overall Brazilian population has increased in the last decade, the actual number of “favelados” in 2010 – 46 million Brazilians – is still larger than the 44.6 million that existed in 2000.

For now, at least, favelas are an integral part of urban Brazilian life. Whether or not you decide to “tour” one is a personal decision, but you’ll inevitably come into contact with them – even if you’re only driving by. Having long ignored them, Brazilians themselves are increasingly depicting favelas in films and on TV. Two of the biggest cinematic blockbusters in recent years, Cidade de Deus (City of God) and Tropa de Elite (The Elite Squad), depict the drug-related violence of favela life.

Meanwhile, the current nightly novela das oito (8pm soap opera broadcast by Brazil’s leading Globo network), entitled Viver a Vida (“Live Life”) features a main character whose sister marries a black marginal and goes to live with him in a Rio favela (to play up the gritty reality – and contrast it with the other characters’ charmed Leblon existences – all the favela scenes are shot with a jerky, hand-held camera reminiscent of the styles adopted in the aforementioned films).

Although neither tours nor films help eradicate the very real and complex social and economic problems that favela dwellers face, visibility and recognition are a good first step.