Via Appia Antica stretches out south of Rome, as straight as a die, its steppingstone cobblestones disappearing into the distance. Monumental Roman structures line the road. ‘The main purpose of the Appia Antica was military,’ says Francesca Mazzà from the Appia Antica Park. Work on the street began in 312 BC, when it was the first proper road leading out of Rome. Today it's still worthy of the ‘Queen of Roads’ nickname it has borne for millennia. By 191 BC, the Via Appia was complete, reaching as far as Brindisi in present-day Puglia.

Besides having enormous military and political importance, the Via Appia Antica was also the road of tombs. It’s lined on both sides by monuments to death. Francesca explains: ‘Roman law forbade that burials should occur within the confines of the city.’ This was for practical reasons, to try to limit disease. ‘There are aristocratic tombs, such as that of Cecilia Metella (daughter of a Roman consul), but also the more simple collective tombs, with open niches for urns.’ Some of the memorials have portraits carved into them, with ordinary, almost recognisable faces that somehow bring the past closer.

Even without considering the millennia-long march of footsteps along here, it’s one of Rome's most singular experiences to cycle down the Appia Antica on a Sunday. People are walking dogs, cyclists whizz past and tourists examine maps, their footsteps following where Roman soldiers forged and Christians scrawled still-visible commemorative graffiti in the catacombs.

This isn’t the Rome that most visitors usually see. It’s la dolce vita, 2015-style. Here, in Pigneto, traditionally a poor working-class neighbourhood full of higgledy-piggeldy, 19th-century low-rise buildings, the alternative has become the mainstream and graffiti-covered shops are fast turning into off-beat boutiques.

Its artery is Via del Pigneto, a partially pedestrianised street bisected by the gritty cityscape of the railway tracks. It’s packed out in the day by a local food and clothes market, and by an eclectic collection of Rome’s bohemians in the evenings.

It’s only in the last few years that Pigneto has become the Roman answer to London’s Shoreditch, with arty bookshop-cafés and nightlife that sees the whole street turn into a nightly party. In a neighbourhood pizzeria, hard-as-nails pizza makers banter with the late-night crowd. Students talk earnestly at spindly tables, groups of friends share beers on doorsteps. Everyone’s wearing black. They’re artists, intellectuals, communists and poseurs, and sometimes all the above.

This was the neighbourhood muse and preferred location of poet and film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, and his favourite hangout, Necci, is still hugely popular – a breezy café/restaurant that opened in 1924, with tree-shaded outside tables.

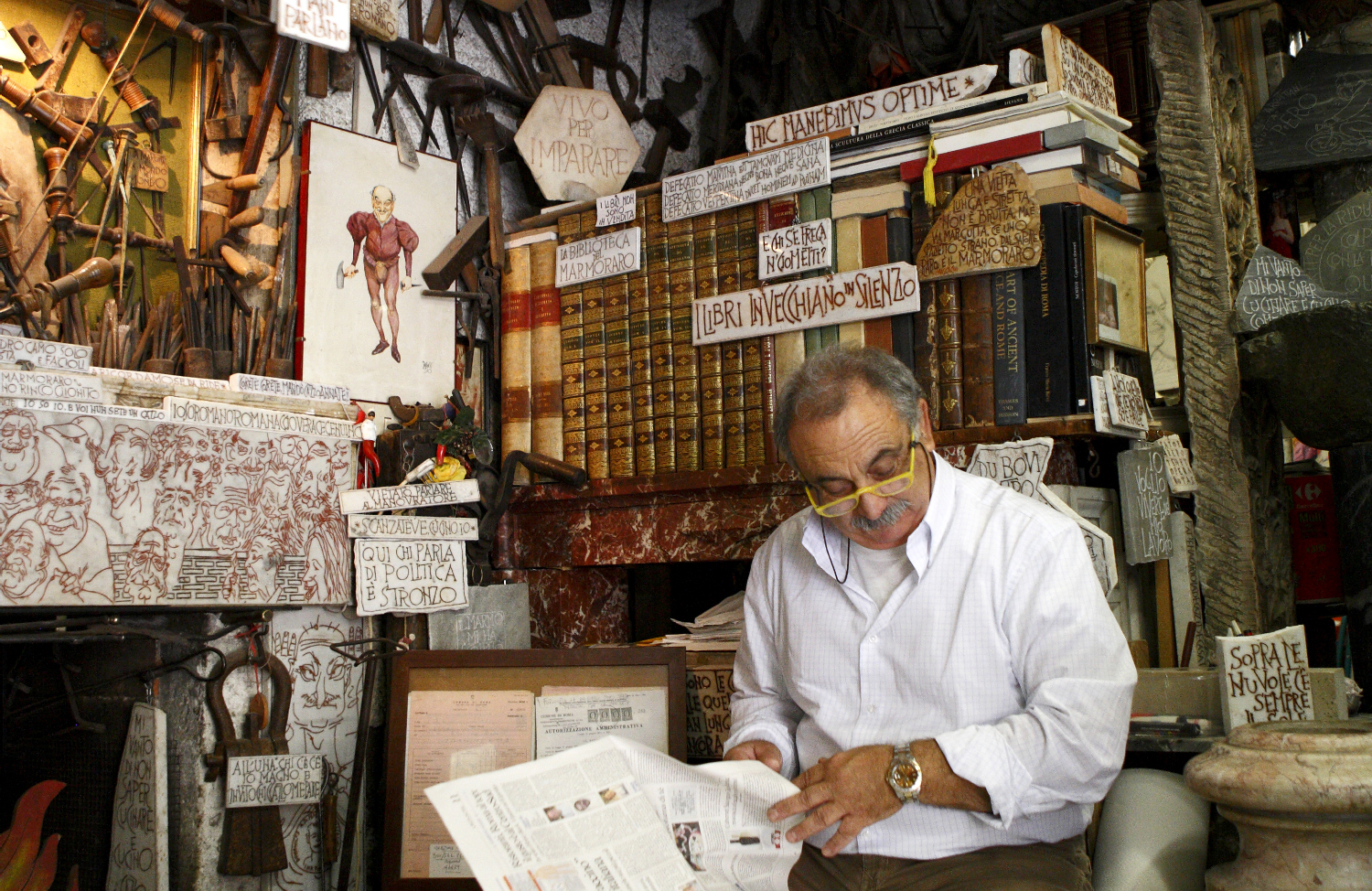

Via Margutta feels like it’s in a quiet village, yet this ivy-draped, cobbled street lies in one of Rome's busiest districts. Start your tour at Bottega del Marmoraro, the studio of master stonecarver Sandro Fiorentini. He will carve any phrase you like on a marble plaque for 15 euros, and these marble engravings can be seen up and down the street. Iconic film director Federico Fellini lived at number 110 and a Fiorentini carving of him and his wife (with a poem) is still on display.

At number 54, you’ll find Valentina Moncada's influential contemporary art gallery (open by appointment only). Her ancestor helped build Via Margutta in the 17th century, working to construct artists’ studios on this very spot. By 1610 many artists, coming to Rome to study antiquities, had begun to settle in Via Margutta because not only was it a quiet tree-lined street, but also Pope Paul III gave artists living here a tax break. Note the pretty Fontana delle Arti (Artists’ Fountain) that bubbles just nearby, decorated with carved easels and palettes, and topped by a bucket of stone paintbrushes.

Beyond the visual arts, Debussy, Liszt and Wagner all worked in studios in the Via Margutta. Stravinsky came with Picasso, and Truman Capote lived at number 33 in the early 60s.

When Rome’s creative scene became dominated by film, Via Margutta became the focus of the 1950s zeitgeist. After all, this was the street of the apartment where Joe Bradley (Gregory Peck) took Audrey Hepburn's Princess Ann at the start of their whirlwind Roman Holiday.

Via di San Giovanni in Laterano is a narrow street that harbours extraordinary underground treasure.

At one end lies the cathedral of Rome, San Giovanni, and, at the other, the Colosseum. The former is a vision of 18th-century Catholic might, topped by wildly gesturing stone apostles. Opposite, almost hidden in a small building, is one of Rome’s most mystical Catholic sites, the Scala Santa (sacred staircase).

Walking downhill to the Colosseum, it’s easy to miss a church that few Romans even know of: San Clemente. The church is 12th century, with an altar surmounted by exquisite mosaics. But another basilica lies beneath this one. More steps lead still further underground. Deep down in the earth is another layer of history: complete rooms that date to the time of the Flavian Imperial dynasty. These 2,000-year-old chambers are thought to have been part of the Ancient Rome Mint. In the dimly lit rooms, a rushing underground stream is audible – and visible, through a hole in the wall. And yet there’s more. A few steps away is one of Rome’s most enthralling sights, a pre-Christian temple, with an altar that depicts the god Mithras killing a bull.

Back above ground, Via di San Giovanni in Laterano continues, innocuous, an attractive but unprepossessing street sloping down towards the Colosseum. It’s quietly busy with its restaurants, clothes shops, a vinyl record store. There’s no inkling of the street’s secret underground life until the end of the road, where some excavated ruins are visible in a large dip. This is what’s left of Ludus Magnus, the gladiator school that fed the great arena.

Layer upon layer upon layer: Via di San Giovanni in Laterano allows a rare glimpse of the many strata of history that lie beneath the surface of the contemporary city. And this is not only the story of a street, but of Rome.