On its 800th anniversary, you can explore Magna Carta’s turbulent history and profound legacy in the castles, fields and museums of England.

Magna Carta (‘the Great Charter’) wasn't the result of a campaign for freedom: instead it emerged from a struggle between powerful aristocrats and a greedy monarch. King John had come to the throne in 1199, and ruled much of western France as well as England. His reign didn't go well: 'Bad King John' lost most of his continental lands and a great deal of his money in a disastrous war with France and was excommunicated by the Pope after a dispute.

The desperate king squeezed his subjects for money, taking over his barons’ estates and imprisoning his opponents and their relatives. In response, the barons took up arms, occupied London and proposed Magna Carta, a treaty that limited his powers. John, pushed into a corner, accepted their terms.

Magna Carta’s 63 articles took in Welsh hostages, the fish-weirs of the Thames and standard measures for wine and cloth. It was intended to strengthen the barons and their allies (who included London’s merchants), not safeguard the rights of commoners.

But Magna Carta also contained two articles that would echo down the ages:

‘No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any way… except by the lawful judgment of his equals’

‘To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.’

Magna Carta was approved at Runnymede, a place of fields and hills by the Thames. It's a pleasant place, although it doesn't have the natural drama of some historical sites. To a large extent that’s why it was chosen: this low-lying floodplain was neutral land, between London (held by the barons) and Windsor (held by the king), and the waterlogged ground meant violence was unlikely to break out – any battlefield would quickly turn into a swamp.

The open fields are an enjoyable place for wander, and paths lead to a neoclassical temple, a memorial to John F Kennedy (technically built on American soil – the plot was gifted to the US in the 1960s) and up the steep hill beyond to the Commonwealth Airforces Memorial. New artworks including a statue of Queen Elizabeth II provide focal points.

To explore Britain’s royal history further, head a few miles northwest to a castle that was built by John’s forebear William the Conqueror, and that – almost a thousand years later – remains the Queen’s main residence: Windsor Castle.

Runnymede is best accessed by car or on a tour – a good way of bringing the landscape to life. There’s accommodation in Windsor, but the closest place to stay is the Runnymede-on-Thames (runnymedehotel.com), a smart, comfortable modern hotel that backs onto the Thames.

London played a vital strategic role in the conflict that led to the Magna Carta – had it not sided with the barons, John would almost certainly not have agreed to negotiate. Two of the four surviving copies of the 2015 Magna Carta can be found at London’s British Library alongside a host of other documents (including Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks and John Lennon’s scribbled lyrics for 'A Hard Day's Night'). An exhibition, 'Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy' (bl.uk), runs until September 2015.

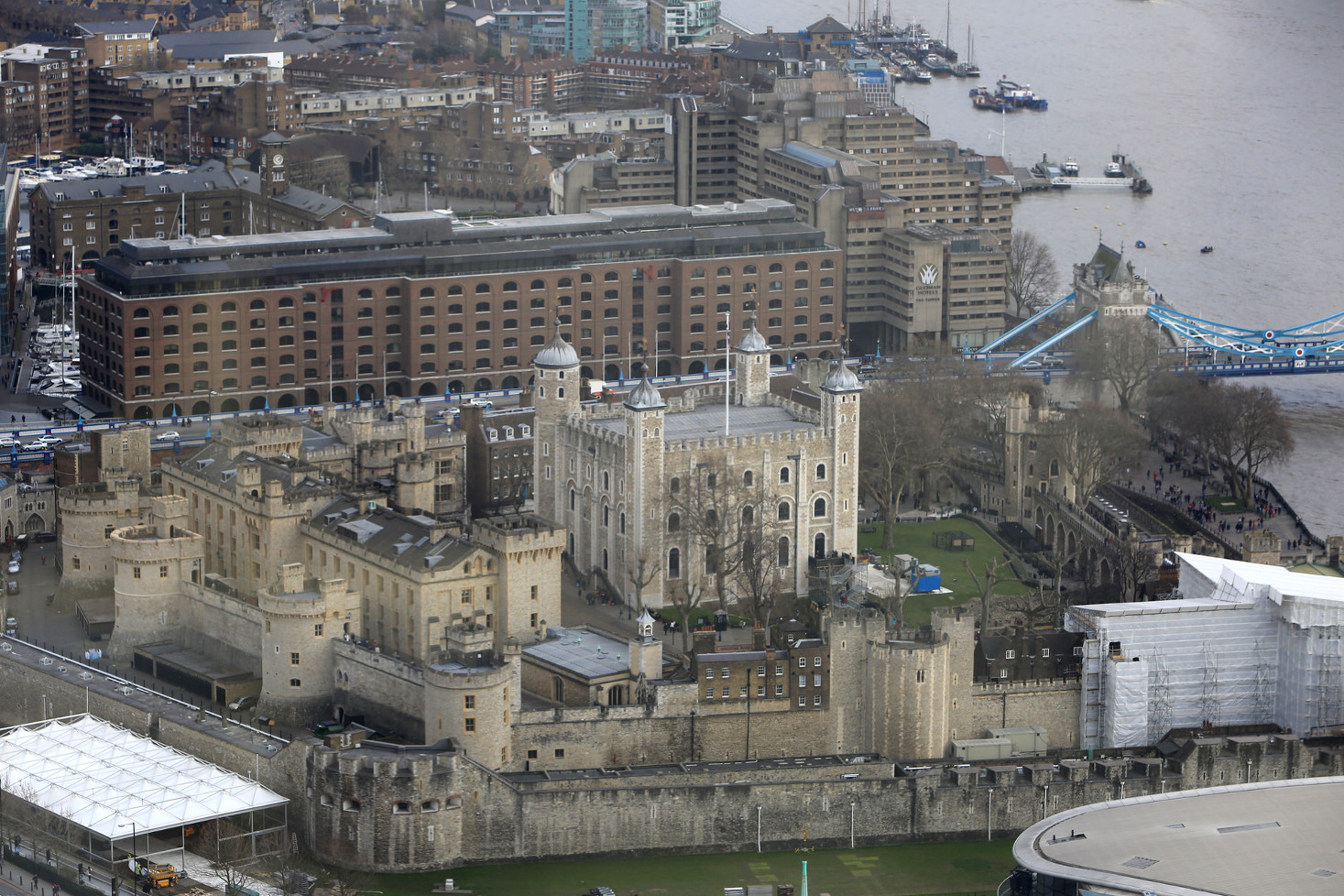

Numerous other London sights have connections to the era, including the Tower of London. John besieged the tower during his the reign of his predecessor, King Richard, and often stayed here: it’s believed he was the first king to introduce lions and other exotic beasts to its menagerie. The British Museum’s Medieval Europe gallery gives a vivid sense of the period, and you’ll almost certainly get sidetracked by the museum’s world class collection of artefacts from across the world. London is packed with places to stay and eat.

The attractive, hill-top Midlands city of Lincoln is home to another of the four surviving copies of the Magna Carta, housed in a state-of-the-art vault in Lincoln Castle. It’s a fine place to get a sense of medieval history: as well as looking at the parchment and accompanying exhibition, you can roam the imposing castle walls and explore Lincoln Cathedral. Once the tallest building in the world (when its towers were topped by great spires that dwarfed the Great Pyramid of Giza), this soaring cathedral is home to plenty of fun little touches — the legendary Lincoln Imp squats on a wall inside, while a modern caricature of a banker sits alongside ancient gargoyles outside, on the southern wall.

Roman remains and Tudor houses sit side-by-side in the historic town, and views stretch out over the green plains of a region that was central to King John’s reign.

The sealing of Magna Carta did not end the story: John had always resented its controls on his power, and rejected the charter just a few weeks after Runnymede. Hostilities resumed, and the campaigning king died in 1216, allegedly after eating poisoned plums (most modern historians agree that he died of dysentery). Lincoln was then the scene for one of the bloodiest battles of the war, when the barons and their French allies were crushed by the forces of John's nine-year-old son Henry III. England’s instability ensured Magna Carta’s significance: shortly after his coronation, the boy-king issued a revised version to gain favour with his subjects, putting Magna Carta at the heart of the country’s politics.

Lincoln also has links to World War II (when it was known as ‘Bomber County’), and airfields and museums offer tangible reminders of the past. The boutique Castle Hotel is an appealing place to stay in town. Lincoln can be accessed by bus or train – nearby Newark North Gate is on the East Coast line, which runs between London and Scotland.

With a glorious 13th century cathedral, a set of historic buildings and Stonehenge almost on its doorstep, Salisbury is steeped in history. Its copy of Magna Carta is stored in Salisbury Cathedral, but it hasn’t always been there: it was originally brought back to the cathedral at Old Sarum, just outside modern Salisbury. Thanks partly to political reasons, Old Sarum’s cathedral was dismantled in 1219, and its stones used to rebuild Salisbury Cathedral. Sarum faded, becoming a ‘Rotten Borough’, and is now a vast, evocative ruin.

That an entire city can be lost to history, but a document – let alone one with such a bloody history, produced in a time when trial by combat was still an accepted legal process – still stands proud is one of history’s wonderful quirks. Magna Carta’s key articles said something to humanity, and still do. Its words, packed onto four pieces of parchment 800 years ago, were carried to America by early settlers and, as well as providing the basis for several key British laws, they informed the American Constitution and provide the words still used by US judges when they brief their juries. Runnymede’s flat floodplain has cast a long and glorious shadow.

Salisbury is a decent base for visitors exploring the south of England: St Ann’s House is a fine place to stay, and London, Bath and Bristol can be easily reached by train or bus.