Mexico’s version of professional wrestling (the term literally means free-style wrestling) is one of the country’s biggest spectator activities today, eclipsed only in popularity by soccer. Characterized by colorful masks, flamboyant personalities and a whole lot of Spandex, it’s an edge-of-your-seat spectacle like no other and something that shouldn’t be missed.

Lucha libre is a unique pop-culture phenomenon whose origins date back to 1863 when a Mexican wrestler, Enrique Ugartechea, first developed the art of ‘free-style’ wrestling based on Greco-Roman traditions. Jump forward a few decades to the early 1900s and wrestling’s popularity started to grow after two Italian businessmen began promoting no-holds barred fights.

In 1933 Salvador Lutteroth Gonzalez, 'the father of lucha libre', established the Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre (EMLL, The Mexican Wrestling Organisation). Within a year of the EMLL’s creation, matches were being sold out. Today the EMLL is known as the Consejo Mundial de Lucha Libre (CMLL; World Wrestling Council) and its home, the 17,000-seat Arena México, is the Mecca of professional Mexican wrestling.

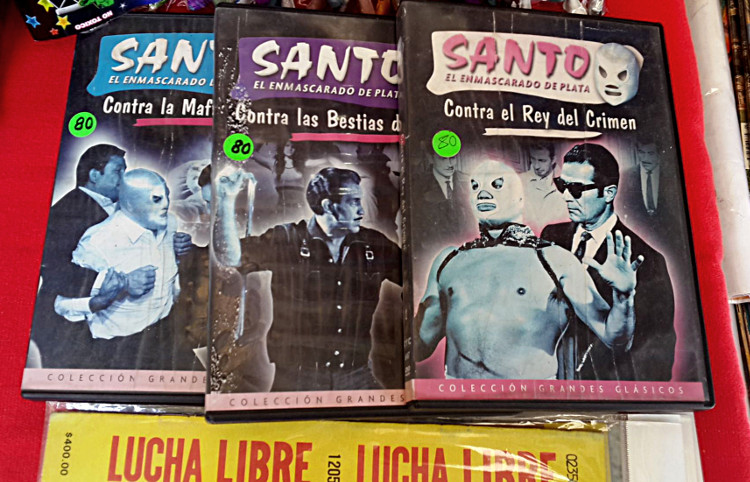

Two key events really helped catapult lucha libre into the mainstream public consciousness. The first was the advent of television, which allowed wrestling to be broadcast around the country. The second was the arrival of El Santo, el Enmascarado de Plata (The Saint, the Silver Masked Man).

In 1942 an unknown wrestler, El Santo stepped into the ring in Mexico City for the first time and won an eight-man 'battle royal'. The Mexican public went wild for this mysterious silver-masked wrestler and El Santo went on to become the most popular luchador (fighter) of all time. His career spanned five decades and he appeared in comic books and more than 50 movies – always wearing his signature silver mask. In 1984, having retired from wrestling, El Santo famously removed his mask just enough to reveal his identity on national TV. It was the first time his face had been seen in public since 1942. He died of a heart attack a week later and his mask was back on for his wake and funeral.

The rules of lucha libre echo those of American pro-wrestling; two or more wrestlers face off in a ring and try to pin their opponent(s) down for three seconds over the course of three rounds. And, much like pro-wrestling north of the border, the stories and stunts of every match are carefully choreographed. Ask any luchador, however, and they’ll tell you that Mexican wrestling requires far more athletic skill; the emphasis in lucha is on spectacular aerial manoeuvres rather than just muscles and brute force.

A typical lucha match involves the técnicos, the ‘good guys’, battling it out against the evil rudos, the ‘bad guys’, with an incredible array of dropkicks, backflips and leg locks. You’ll see both luchadores and luchadoras (female wrestlers) whirling around the ring, as well as wrestlers in drag known as exóticos. Campy and flirtatious, these fighters body slam like the best of them in between blowing kisses to the crowd. And then there are the dwarves, known as los minis, who may or may not get thrown around the ring. No one ever said that lucha libre was politically correct.

Flying scissor kicks and wheelbarrow holds aside, it’s los enmascarados (the masked ones) who constitute the biggest difference between American and Mexican wrestling. A mascara (mask) is worn by most luchadores, even in public, thereby keeping their identities secret.

The story of the masks goes back to 1933 and the owner of a footwear company, Don Antonio H Martinez, who created one for a wrestler known as El Ciclón McKey (The Cyclone McKey). The mask was nearly impossible for an opponent to remove in the ring and the idea proved such a success that mascaras have been used in lucha libre ever since. Martinez’s original store is still in business today, located just behind the Arena México.

The biggest lucha matches involve two luchadores betting their masks; at the end of the fight the loser must remove their mask and thereby reveal their identity. The longer a luchador can defend their mask over the course of their career, the higher their status in the ring and the world of lucha libre. Luchadores who don’t wear masks may wager their hair, the loser being forced to have his hair publicly shaved.

–––