Facelifts, nose jobs, chadors teamed with Japanese sun visors, rare artefacts and friendly people – Iran is a fascinating paradox.

Somewhere to the east of Shiraz, we reach a village so tiny it's not even a dot on the map. No doubt its residents will regard the prospect of an unexpected visit from a busload of Westerners as the next best thing to a Martian invasion.

Nonetheless, our Farsi speaker takes his chances and is soon back with the answer. A group of men from the village will sit down with us in its mosque-cum-meeting hall. We troop in after removing our shoes and settle down to a question-and-answer session about the routines of village life and the way the people extract a living from the arid land on which they've made their home. There is some farming, but most of the men travel to jobs in other towns.

Then the five women in our group are invited to talk to the village's women and, after some hesitant introductions, the children join us and the place erupts in a frenzy of photo-taking. Faced with a camera lens, they all turn out to be naturals, mugging, striking ingenious poses and dragging us into the frame with them. Amid the mayhem, one of our group, a doctor, is asked to dispense some impromptu medical advice to the women – mainly about back and knee problems. She does her best, suggesting herbal alternatives to the drugs she knows they won't be able to get in this part of the world. When at last we leave, our preconceptions thoroughly confounded, we're waved off by the whole village,

I'm with a group of friends travelling through Iran by bus, aiming to glean some insights into the lives and hopes of the country's people.

We've read about the Iranian preoccupation with nose jobs and hair transplants. Now, we have the proof.

We start in Shiraz and at breakfast on the first day, comes our first surprise: the number of hotel guests wearing bandages either on their noses or the backs of their heads. We've read about the Iranian preoccupation with nose jobs and hair transplants. Now, we have the proof.

In the bazaar, we find a currency dealer to change our US dollars into fat wads of rials and tomans. Then we shoulder our way through the bustling alleys, gazing at the variety of ways in which the word "hijab" is interpreted. As we expected, many women wear the black chador, which leaves only the face and hands visible, but you could design a fashion spread around the accessories and variations – from the chadors teamed with Japanese sun visors to the headscarves topped by Dolce and Gabbana baseball caps worn backwards.

That night, we get another look at fashionable Shiraz during dinner at Haft Khan, a five-storey restaurant complex designed to incorporate a contemporary take on traditional Persian architecture with the techniques and motifs of modern industrial engineering.

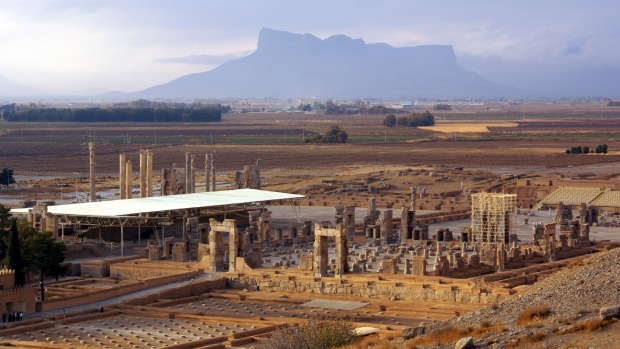

We're not ignoring Iranian history altogether. We take off next morning for Persepolis, where we're astonished by the scale and detail of what remains of this 2540-year-old monument to the grandeur of the Achaemenian empire. It lay forgotten for centuries after Alexander burnt much of it down in 330BC, but it's since become notorious, thanks to the last Shah and the spectacle he staged there in 1971 to celebrate the 2500th anniversary of the Persian monarchy. Royals and heads of state from all over the world attended, food was flown in from Maxim's in Paris and a luxurious tent city completely redefined the concept of camping out. Iranians were so disgusted by the excess, it is thought to have hastened the revolution. It also turned them off Persepolis, which was to lie neglected once more after the party was over.

We get a more intimate view of Persian history during a night spent at the country's only functioning caravanserai, the 400-year-old Zein-O-Din, on the road to the city of Kerman. Once part of a widespread network of caravanserai, it has been meticulously restored, with curtained bedrooms, furnished with mattresses laid out on carpeted platforms, arranged around a central courtyard. Fortunately, the plumbing in the communal bathrooms is not similarly in-period. This is also an ideal place for star-gazing. We skip the astronomy lessons, which take place on the roof, to take an illuminating nocturnal desert walk.

One of the trip's chief delights lies in the fact our Farsi speaker is able to strike up conversations with people we come across in the villages, streets, gardens and bazaars. Most of them are eager to talk and all of those who do, come up with stories you won't find in a guide book.

By the time we arrive in Isfahan, the long bus rides we've been taking across the country's desert expanses have really begun to pall, but the city, Iran's third largest and its most beautiful, proves a great antidote to all that emptiness. We're in luck and the river, which is often diverted to the neighbouring city of Yazd as part of a controversial water-sharing project, is in full flow. Families are strolling along its banks and across the arched pedestrian bridges, which are among Isfahan's most romantic features. Of the 11, five are centuries old and at night, they're artfully lit so that the reflections dance across the water beneath.

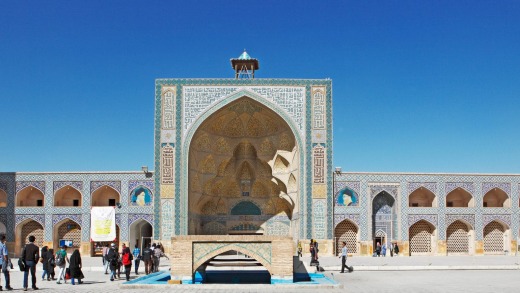

Like most visitors, we head for the vast 17th-century square at the city's heart. A World Heritage site, it is second in size only to China's Tiananmen Square, but the comparison ends there. It is dominated by the magnificent Jameh Mosque, a building that has been part-destroyed, rebuilt and enhanced by successive regimes during its 900-year history. We watch worshippers arrive for Friday morning prayers while we women wrestle with a strong breeze to control the swirling chadors we have to wear just to stand at the entrance.

In Isfahan's cemetery for those who died in the Iran-Iraq war, we go wandering among the headstones, which are marked by large photographs of the dead soldiers. About 1 million Iranians died during the eight-year conflict and, as the graveside portraits poignantly confirm, many of them were barely into their teens. We meet a man who is making one of his regular visits to the grave of his son, a volunteer at the age of 18. When the boy came home on leave, the man says, he offered to take his place, but his son refused to let him and was killed soon afterwards.

Our trip winds up in Tehran, where we supplement a tour of the former US embassy by calling on another haunted house: the Niavaran Palace, where Mohammad Reza Shah, his queen, Farah Diba, and their children lived for the last decade of his reign. Set in gardens in the foothills of the Alborz mountains in the north of the city, the palace was built in the early 1960s and its architecture has the faded modernism typical of the era.

Inside, there's a more exotic mixture of styles. The palace's Persian heritage is declared by its mosaics, mirrors, chandeliers and carpets, but works by Miro, Picasso and Chagall attest to Farah Diba's interest in art and a display of her gowns reflect her love of fashion and design. But it's an eerie place, at its creepiest in the children's bedrooms, with their stuffed toys and model aeroplanes.

The bus trip back to the hotel offers a more upbeat experience. We stop for a look at north Tehran's two-year-old Tabiat Bridge, which was designed by a female architect, Leila Araghian, as a pedestrian footbridge spanning a gorge dividing two stretches of parkland. It's an enticing piece of engineering – as graceful as a cat's cradle, yet robust enough to house a couple of restaurants. Strolling along on one level, we see people sitting at dinner on the tier below.

But our biggest Tehran surprise comes during a tour of the offices of one of the country's daily newspapers, which was nationalised after the revolution. The company's managing director is an imam who went into exile in Paris in 1978 with the Ayatollah Khomeini. A jovial character, he gives us a lengthy interview, before insisting we stay for lunch. And when the food comes, he is a generous host, going around the table to serve each of us with large mounds of food.

Just as friendly are the students we come across one sunny day during a pre-lunch walk in a Tehran park. They are talking about chance, they tell us, and whether you can subvert it by making your own luck.

All fans of the internet, they resent the fact certain sites are blocked to them. And they don't want to do military service. They are already working on their excuses. One is the head of his family now that his father is dead; another is the son of divorced parents, so he, too, is wanted at home; a third cheerfully agrees he is too fat; and a fourth confesses to sweaty hands – no good for handling a gun.

They finish up with an impromptu concert. One of the household heads performs his own rap song. It is in Farsi, but our interpreter gives us the gist. It's a playful rant about the lassitude that its creator sees in Iranian society. When we say goodbye, they're looking happier. So are we. In this case, chance has been on their side – and ours.

They've just given us more evidence of what we've noticed everywhere we've been in this big, diverse, contradictory country. It's full of people who can't wait to engage with the wider world.

MORE INFORMATION

politicaltours.com.

smartraveller.gov.au.

GETTING THERE

Several major airlines operate flights between Tehran and Australian capitals. You can also fly into Shiraz via Dubai and Bahrain. Emirates has a connecting flight with Gulf Air.

Once in Iran, it's possible to travel around the country by bus. The British company, Political Tours, also organises tours to Iran. It works with a local travel agency and has guides of its own. These are journalists or authors with specialist knowledge of the country and its politics. Often, they are Farsi speakers. See politicaltours.com.

TRAVELLING THERE

You should allow plenty of time to obtain a tourist visa from the Embassy of Islamic Republic of Iran in Canberra. The application form can be downloaded from the embassy website: iranembassy.org.au, or contact a travel agent. Female travellers are required to adopt the hijab, which means covering the hair, at least in part, and wearing trousers with long shirts or jackets.

STAYING THERE

Grand Hotel Ferdowsi in Tehran has double rooms starting at $US154 ($216). The hotel is close to the main museums, as well as being within walkable distance of the market. The rooms are comfortable, with Wi-Fi, but the decor verges on the bizarre. See ferdowsihotel.com.

Abbasi Hotel, Isfahan, has double rooms from $224 a night. Isfahan's most luxurious hotel, it began life 300 years ago as a caravanserai, and is set around beautifully landscaped gardens with a traditional teahouse. See abbasihotel.ir.

SEE + DO

Buy hand-painted miniatures in the Isfahan market and watch the currency trading at the outdoor exchange at the market entrance in Tehran.

Ogle the Iranian crown jewels, held in the National Jewels Museum in the vaults of the Central Bank, Ferdowsi Street, Tehran.

Supplement a trip to Persepolis with a visit to the National Museum of Iran, which has carvings, pottery and stone sculptures excavated from some of the country's most important sites.

DINING THERE

Haft Khan Restaurant Complex, Quran Boulevarde, Shiraz. See haftkhanco.

Coffee Shop and Veggie Restaurant of Iranian Artists' Forum, Artists' Park, Tehran. Combine lunch here with a visit to the contemporary galleries in the Artists' Park.

Sandra Hall travelled at her own expense.

See also: Why you should visit a Muslim country