Its early morning and the sun is just starting to burn off the mist rising from the still, shallow waters of Inle Lake. Huge dragonflies dart about at head height, like toy helicopters, easily matching the boat for speed, and overhead a snow-white egret drifts by, searching for a new, more stable patch of water hyacinths from which to catch breakfast.

Other fishermen are out on the water too, silhouetted in the millpond-calm surface of the lake, standing on one leg at the back of their dug-outs in tatty longyis and conical bamboo hats, gently pulling in their nets. With both hands otherwise engaged, they propel their little craft forwards with one leg pushing at a paddle and cradling its handle in the socket of their armpit in a style all of their own invention.

Large wooden houses built on teak stilts appear up ahead, many of them almost mansions in size, and the village which sits plum in the centre of the lake is surrounded by fields of green as far as the eye can see. The wake of the boat collides with the edge of the fields and a ripple runs the length of the plantation, as if a giant mole were tunnelling just underneath the surface. This Garden of Eden does not have its roots on terra firma but reveals itself to be an ingenious and fecund market garden, floating on the surface of the lake, yielding such bounties as to explain the outsized houses in the village.

At high water, after the annual monsoon, someone poking around the grassy mudflats at the southern end of the lake noticed that the grass there, to save itself from being covered by the flood waters, detached itself from the mud below and floated to the surface until the waters receded. Now each year, huge 200 foot long strips of this buoyant turf are cut and gingerly pushed to the village where they are pinned in uniform rows by long bamboo poles that anchor them to the mud below. Silt and lake weed are piled on top to create the perfect growing medium for tomatoes, peppers, courgettes, squash and more. In this flooded pick-your-own farm, down each manicured row of plants the pickers can be seen plucking their fruits from the wobbly comfort of a long, narrow boat.

Today is full-moon day, a holiday for the hill farmers who pour down to the lake in their tribal finery to visit the temple, cook up some curry and socialise. At Indein village, a gaggle of Pa-O ladies, all in their distinctive black robes with dragon turbans of the brightest orange, are boarding a longtail. Clearly unused to travel by boat this is a great novelty and there are hoots of laughter. Given it is a holiday, Indeins 1,054 temples and stupas might be expected to be very busy with pilgrims, but the whole site is empty. A Banyan tree grows out of the top of a 600 year-old stupa adorned with intricate carvings of ogres and mythical birds and the roots of a fig curl serpent-like through the cracks of an elaborate temple, where Bhuddas head has long-since vanished and the relic chamber has been plundered. Add in some monkeys and Indein would be a spit for King Louis Palace in The Jungle Book romantic, tumbledown and just one small step away from complete collapse. The Pa-O ladies, and seemingly all their neighbours, relatives, friends and foes are all at the gaudy, gilded Phaung Daw Oo temple, out on the lake, untroubled and uninterested by the temples of the past.

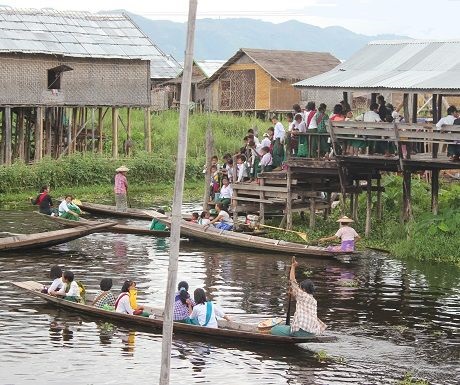

Its mid-afternoon now, and suddenly an explosion of children emerge from the high school, a torrent of green and white heading for the jetty. A flotilla of longtails awaits to ferry them home through the canals of the village. Mum is still picking tomatoes and Dad is somewhere digging silt or hunting giant water snails with which to bait his eel traps, or very possibly sitting at a neighbours house watching the Premier League over a large glass of Grand Royal enjoying life as he is instructed to do in the omni-present whisky advertisements. So Grandma steps up to the plate, evidently relishing the opportunity to open the throttle on the large outboard motor as, cheroot in one corner of her mouth, she whisks dozens of small children home along the waterways, in time for their green tea and rice crackers.