"How come you know so much?" I ask Ares Garcia, nicknamed "The Hair Man" for his wild, dark mane. He sits opposite me in a hole-in-the-wall restaurant in Old Havana, his head a riot of curls. The waiter delivers mojitos choking on mint leaves and whole green peppers stuffed with succulent mincemeat – an unexpected delight in the supposed culinary wasteland that is Cuba.

"I read," he replies, eyeing me straight on. "I read everything. In my taxi I have three books. In my bedroom I have another four. I read my engineering books, maths, of course. In my bedroom I have newspapers. I don't like – what is it called, the electronic book? – Kindle? I don't like Kindle. I prefer real books."

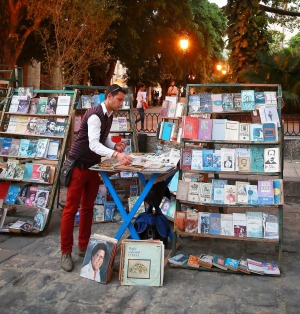

The road to enlightenment, it seems, is paved with books. All along the Obispo in Old Havana, in the plazas that unify this rabbit-warren quarter and the government-run post offices that spill out onto its side streets, Spanish translations are propped up for sale: poetry and literature, politics and propaganda, crime and romance.

There are volumes by Jose Marti and Jose Lezama Lima and Fernando Ortiz, lightweight contributions from Jeffrey Archer and Danielle Steele, works of genius by Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Ernest Hemingway, and an infestation of soft-covers bearing the striking young faces of Cuba's revolutionary heroes: Che Guevara, Fidel Castro and Camilo Cienfuegos.

Garcia has absorbed them all. An engineer who once worked for the government, he guides tourists around his city in the daytime, and drives a taxi by night. He's one of few Cubans to own a car, a Russian-built Lada given to his father by the government as reward for hard work, and now re-gifted to the son. "It's small," he says, "but it's my car."

But Garcia has dreams far bigger than squeezing into a boxy Lada and working his way through an endless supply of books while he waits for passengers. Political events at home and abroad are conspiring to help him: not only has his government relaxed its once-strict collective model of ownership, but just last month President Barrack Obama announced that in 2015 the US would begin dismantling its five-decades of embargoes against Cuba. Garcia's enthusiasm cannot be contained.

"You've heard the news?" he'd asked when we first met. "It's very good for us. Raul Castro phoned Obama on December 17, and I had my first American customers on New Year's Eve."

Political change is reshaping the way people operate all over Cuba: private homestays and restaurants have exploded in number in the past three years, with citizens desperate to capitalise on a strong, lucrative tourism industry. Now, the loosening of travel restrictions by the superpower whose most southerly continental point lies just 140 kilometres to the north might well result in a tsunami of arrivals; even as we speak, Garcia's wife is at home perfecting her cooking skills for the restaurant they plan to open.

"Our own privacy business," he explains, using a quaint, anglicised term for emerging, profit-based enterprises. "Our small business is Italian food. Now we begin."

I want to be happy for him, for a world that has existed only in his books and his imagination is finally opening up to him. But I'm uneasy, too, for surely this truce with the US will result in an influx of funds and influence that will erase the peculiarities that make Cuba so appealing: the delight of mid-century cars trundling along the road as though on some period film set; the architectural masterpieces reduced to decay; the absence of fast food franchises; the collectivist ethic; the people who walk with heads held high instead of bent over mobile phones, and who've been forged by isolation and hardship into a nation of resilient, well-informed and charmingly defiant citizens.

It's a concern mirrored by Australians eager to get to this tiny socialist outpost before it changes with operators already reporting an increase in the number of inquiries about Cuba. But tourists can't expect the Cubans to remain marooned in a previous century so that their own, romanticised conception of the place might be preserved. Transformation has always been inevitable; Cuba's metamorphosis has begun, and visitors must now bear witness to a new and unfolding history.

Out on Obispo the atmosphere is festive: weaving among the carts selling cheap, government-subsidised ice-cream and churros and roasted corn on the cob are entrepreneurial folks demanding their share of the profits. Souvenir shops drape their doorways with T-shirts and aprons and shopping bags emblazoned with Che Guevara's pervasive image; waiters employed by private restaurants hold menus aloft amid the churning foot traffic; homestay proprietors shop for pots of bright paint and flowing drapes and works of art with which to transform their neglected, neo-classical beauties.

Opposite Hotel Ambos Mundos – the famed establishment where Hemingway had a suite from which he could see the rooftops of Old Havana and the canal and the Spanish-built fort across the water – an Afro-Cuban woman named Julia catches my eye. Her neck adorned with beads, head wrapped in a slave-style panuelo, lips grasping a long cigar, she preens and twirls for the camera. Three pesos, she shouts out, her smile snapping shut as I lower my camera and then unfurling again in a flash of white teeth and crimson lips as I place the money in her outstretched hand.

But the capitalist instinct is tempered by a love of socialist values that seems to run like electric current through these people's veins. It's an ethic embodied by a story that's unfolding further down the boulevard, where a dreadlocked, bearded mime stands deathly-still on the pavement, lacquered from head to toe in black and gold paint. He's mimicking a statue of Jose Maria Lopez Lledin, who was known, inexplicably, as El Caballero de Paris (The Gentleman of Paris).

A resident beloved by all Havana, he came to Cuba from Spain as a boy in the early 20th century and, suffering mental illness as an adult, took to living on the streets – an uncommon practice in this communal country where even the poorest of people's needs are met. The gentleman accepted food from concerned locals only in exchange for gifts of his own art and craft. The statue which the mime represents now stands as a commemoration outside the Church of St Francis of Assisi at the ferry terminal in Old Havana; Cubans stop by each day to touch it for good luck.

Garcia observes the scene. Progress is a blessing for Cuba, he says, but the good that has prevailed here since the revolution – care for the needy, first-class education and healthcare for all, protection of the least powerful – must never be thrown out with the bad.

That night I sleep fitfully, for Old Havana is alive with music and dance and other expressions of nocturnal joie de vivre. The quiet in the early hours of the morning is soon washed away by incessant rainfall. In the morning my homestay host makes fresh guava juice in the kitchen next door while I sit at his dining room table eating plates of tropical fruit and eggs with cheese and jamon. Cuban coffee – a crop now fallen on hard times and as yet still exiled from the coffee-loving, captive market of the United States – flows thick, strong and delicious.

Roger Blanco Morciego picks me up after breakfast in a 1955 Chevrolet. It is shiny blue and white with plastic-covered, turquoise vinyl seats and pink fluorescent lights set into the roof panel. "It would be sacrilege for you to come to Cuba and not ride in a vintage car," he says.

We're on our way to Hemingway's casa on the outskirts of Havana, to which the writer decamped from the Hotel Ambos Mundos after winning a few Pulitzer prizes and so improving his financial prospects. On the road ahead, just past Havana Port, water has dammed after last night's rain. Our driver proceeds straight through it, and soon water is seeping in through the doors and rapidly filling the foot-well. The engine chugs and misses a beat, but now we're clear of the deluge and wheeling happily along the tar. The driver opens his door and shakes a little in his seat; the water drains clean away.

All the way to Hemingway's casa, Morciego delivers commentary on the outmoded cars that pass us by. Though they're utilitarian objects, the Cubans understand the appeal they hold for foreign tourists: they line up along the Malecon in Old Havana in all their glossy glory, waiting for passengers to hop inside. Considered national treasures, they can't be removed from the island, I'm told.

Morciego points out Buicks and Dodges, Chryslers and Chevrolets, Oldsmobiles and Fords; they appear in a terrific blaze of colour: hot pink, lime green and red, purple, cobalt and gold. Like most Cubans, Morciego has never owned a car, yet he knows with barely a sideways glance the model and make and year of every American automobile to set wheel on these roads.

The casa, left as a legacy to the people of Cuba, is modest and warm, and from its perch on a hill has a view that – if not for the haze and encroaching development – might reach all the way down into the bowels of Havana. There in the pool house is the photo of Hemingway with Gregorio Fuentes, one of the men said to have inspired the character of Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea. There, smiling out at us in black and white, are the faces of Mary Welsh, Hemingway's wife; Rene Villarreal, the poor kid from Havana who became Hemingway's honorary "godson" and was the only person allowed into the room while he wrote; and the stream of visitors the writer would entertain at his Cuban country house. People of all professions are represented here, except for wordsmiths, it seems.

"He hosted famous actors, people he met on his travels – but very few writers," says Morciego. "Maybe he was scared of competition."

If this statement bears even a grain of truth, it was a folly to be sure: today, more than half a century after the American Nobel laureate's death, the Cuban people still cherish him. Regular research colloquiums are held with a special focus on Hemingway. Gatherings of writers and intellectuals and academics determine ways to distil the essence of his brilliance and the influence of his own writing on that which has emerged from Cuba in the years since his death. Cuba, in a somewhat subversive and surely defiant act, has co-opted that great son of American literature and claimed him as one of its own.

We climb back into our 1955 shiny blue-and-white vinyl-seated pink fluorescent-lighted Chevrolet and roll slowly down Hemingway's driveway. I turn and stare out the car's back window at the shady copses of turpentine and cedar, mango and palm, frangipani and bamboo, at Hemingway's unassuming casa framed between the wings of the American Chevrolet. How odd it is, I think, for the United States to be so thoroughly divorced from this country, and yet so utterly omnipresent.

The writer was a guest of Intrepid Travel and Urban Adventures

intrepidtravel.com

urbanadventures.com

Qantas flies to Mexico City from Sydney via Dallas/Fort Worth and from Melbourne via Los Angeles. Cubana flies from Mexico City to Havana. See qantas.com; cubana.cu.

Intrepid Travel offers tours from eight to 22 days specialising in themes such as cycling, music and dance and sailing. An eight-day trip costs from $1060. Urban Adventures has city-based tours and custom-designed day trips. A half-day tour costs from AU$50 See website addresses above.

All Australians travelling to Cuba must have a visitor's permit, which can be obtained from the Cuban consulate in Canberra. See cubadiplomatica.cu.

Australians travelling in Cuba often encounter problems accessing funds. Euros and Canadian dollars can be exchanged for CUC (Cuban convertible pesos) and cash advances can be obtained from banks, large hotels or Cadeca exchange houses. Credit cards, debit cards and travellers' cheques are not currently accepted if issued by US banks or Australian banks affiliated with US banks. It is best to travel with plenty of cash and, if using credit or debit cards, to consult your bank before travelling.

Celebrated Cuban dancer Carlos Acosta's debut novel spans four generations and is set against the backdrop of a rich and lively history encompassing slavery, colonialism, African mysticism and – of course – revolution.

Ernest Hemingway's Nobel Prize-winning masterpiece unfolds in the deep gulf north-east of Havana, a city whose fading night-time glow is beautifully evoked as the book's protagonist, Santiago – hooked to the biggest marlin he's ever seen – is pulled further out to sea.

Cuba's history, culture and politics are voiced through the writings, artwork and testimonials of Cubans both well-known (Jose Marti, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara) and unfamiliar (slaves, prostitutes and activists).

How long does the romance of revolution last? This question is answered by everyday Cubans deeply affected by the revolution, the US embargo and the termination of Soviet aid in the 1980s.

Flor Fernandez Barrios recalls a childhood during which the newly-installed revolutionary government seized her family's plantation and – when the family requested permission to emigrate – sent the then-11-year-old Flor to a rural work camp where she was made to pick tobacco and sugar cane.

Cuba's not a foodie destination? Dispel that myth with an exploration of the country's rapidly transforming culinary scene. Beyond the rice and beans that are a staple of Cuban fare, visitors will find local, organic produce used in an inventive blend of Spanish, African and Caribbean cuisines. There's also plenty of opportunity to eat out in paladars –privately-run restaurants, often operating from family homes, that have proliferated in Cuba in the past three years.

Dance lies at the heart of Cuban culture and Havana is filled with studios where visitors can develop their skills under the tutelage of experienced Cuban dancers. Experience isn't necessary: courses are organised according to individuals' abilities and dance partners can be arranged for solitary visitors keen to kick up their heels around town.

Music is an ever-present backing track on the streets of Cuba, and musicians and lovers of music alike will find themselves deeply immersed in this vibrant, defining culture. Live performance is standard in bars and restaurants, on street corners and homestay rooftops; specialist tours will take travellers to the very heart of musical practice, with opportunities to play and record music and meet the people behind Cuba's rich musical heritage.

From the natural paradise of Vinales in the west, through the coastal enclaves of Cienfuegos and Trinidad and all the way to the Sierra Maestra in the east where Castro's revolutionary base and the country's highest peak are located, Cuba is a walker's paradise. The country unfolds at a slow pace when seen from street level and offers frequent encounters with the locals and the country's superb natural environment.

Best-known for its history and culture, Cuba is also a rich destination for birdwatchers and those who love to focus on the minutiae of the outdoors. Home to pristine biosphere reserves and UNESCO-listed sites such as Vinales Valley, Topes de Collante and the eco-diverse Zapata Swamp, Cuba will reward the attentive visitor with sightings of birds, endemic flora and fauna – and the world's smallest frog.

Changes are afoot with the historic relaxing of the US embargo on Cuba. We asked Intrepid Travel's Martin Ruffo, an expert on travel in the Americas, how Australian travellers will be affected.

Will the lifting of the embargo threaten the characteristics that draw travellers to Cuba?

These things we find appealing, most Cubans would change in the blink of an eye if they could. Modern cars may one day replace retro ones and buildings may stop crumbling, but that's only part of Cuba's charm. Nothing can take away the natural beauty of Cuba, its history and most importantly, its people. The hardship Cubans are going through has made them the beautiful people they are today – educated, vivacious, adapting, friendly, life-loving and generous

Will an increase in the number of American tourists visiting Cuba detract from its appeal as a country that has prevailed in the face of American disengagement?

Cuba is on bucket lists for many reasons – but none of these reasons are because it has been "American free". The destination isn't going to change overnight – there is still a limited tourism infrastructure – so there is an opportunity for the government and tourism industry to develop authentically and sustainably.

How can Australians reconcile their desire to visit a Cuba free of modern Western influence with the Cuban people's desperate need for economic development?

From talking to Australians it seems there is a concern that Cuba will somehow become over-developed, as has happened in some destinations such as Bali. The reality is that, like Bali, there will be some busier towns and tourist areas, but for those wholook to get under the skin of a destination there will always be special places to explore in Cuba.

What is your advice to Australians keen to travel to Cuba but concerned about the changes?

Cuba will change, one way or another, sooner or later. The Cuba of today is not the same Cuba of 10 years ago. There are more home stays in more destinations than ever, food is better than before, transport is better than before – it has certainly become more accessible to tourists. Seeking a local, grassroots experience will enable people to see the authentic Cuba, whenever they decide to go.