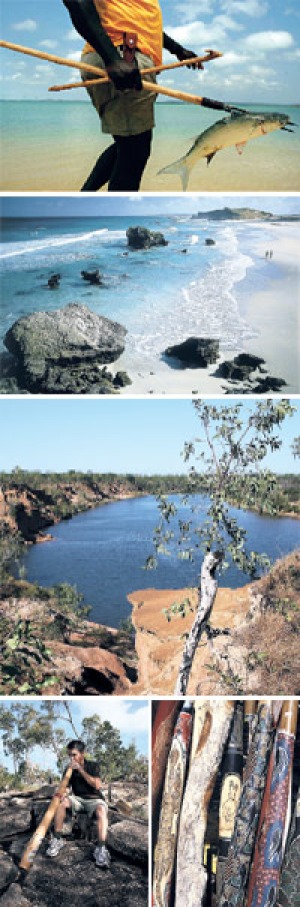

From hunting to bush cooking, fishing to didgeridoo playing, Max Anderson experiences three remarkable indigenous tours.

Aboriginal tourism experiences in Australia are described in many ways but the words "dynamic" and "exciting" are rarely used. Be honest, how many times have you listened politely to abstract and slightly dull Dreamtime stories while circling a landmark? Held a boomerang in circumstances that owe more to hotel lobbies than hunting parties? Or come away feeling that, while you connected fleetingly with culture, it would have been nice to connect with an Aboriginal person? Unreliability, inconsistency and poor delivery stymie the best efforts of many well-intentioned projects but others are simply uninspiring, stubbornly clinging to the old-fashioned model of the walk-and-talk guided tour.

To some extent, non-indigenous domestic tourists get what they deserve, because we (and I'm one of them) have never really asked much of indigenous tourism. Most of us have clearer (and higher) expectations of an Arctic stay with an Inuit, an encounter with a Thai hill tribe or a desert trek with Bedouins.

Last month I reviewed three indigenous tourism experiences in the Top End, where culturally immersive enterprises are being fostered by the Northern Territory government. Each was extraordinarily different and revealing. And, after 20 years, I found the Aboriginal adventure I always wanted.

RripanguYidakimasterclass Soh is a young Japanese man with limited English but an expansive vocabulary when he plays his yidaki - the eastern Arnhem Land word for didgeridoo. He's at the feet of a yidaki master, Djalu Gurriwiwi, a 75-year-old Yolngu elder in Hawaiian shirt and wraparound shades, described on a website as "Mr Didgeridoo".

Gurriwiwi points a heavy didge at Soh's chest and plays a complex piece called "the dolphin". Feeling the beat of air pressures on his solar plexus, the student is supposed to absorb the technique. It's how Gurriwiwi learnt as a child, building a repertoire of a thousand songs. It's how Soh and I are learning today.

But is it a good experience?

Soh has paid $900 for a three-day Rripangu Yidaki masterclass held in Birritjimi, a small Aboriginal community near Nhulunbuy on the Gove Peninsula. He's from a culture obsessed with order and aesthetics and here he is, sitting in a breezeway surrounded by camp dogs and half-dressed kids with a busted sofa out by the road. Even behind the houses, where some Shinto-like calm is lent by palm trees and the Arafura Sea, the scene is dominated by a giant bauxite refinery.

Yet the face of the young Japanese man shows only respect. And joy.

My own respect and joy was tempered when the four-wheel-drive collected us from the hotel 30 minutes late; it was filled with extended family and dust and it detoured to buy water, cigarettes and phone cards. And now I'm playing poorly for Gurriwiwi, which means more chest lessons.

"Brr-brrr," the master says, wagging a finger before his lips.

"Ah," says Soh.

"Hmm," say I.

Two hours later we're in the bush cutting yidakis.

The Gurriwiwi family spreads out, tapping trunks with axe-heads for hollowness, and soon the hot forest rings with thuds and crashes. The master points to a 30-metre tree and tells me: "This one." Felling any 30-metre object is a daunting proposition but I pull it off, before being requisitioned to saw and lug the 40-kilogram yidaki for 300 metres. Clearly, the old boy figures I labour better than I play - and suddenly I'm laughing. Stinking, filthy but laughing.

Back at the community, I feel my playing has improved - until 12-year-old Mikey takes one of our yidakis and smashes through a routine, a virtuoso performance born of millennia of children having yidakis played against their chests. I ask him to play "the dolphin" and the hairs on my neck stand up.

On day two, I don't care that the truck is late and instead of extended family and dust I see Gurriwiwi, his wife Dhopiya, daughter Selda, son Vernon and a few kids who giggle with their confounding array of aunties. I pat the camp dogs.

Soh whittles raw yidakis with Gurriwiwi. We practise in long grass beside the Arafura.

Our last day is wonderfully weird and free-form.

We visit a beach fronting the refinery, where Gurriwiwi, Soh and I take turns to play the yidaki in the shade of a tree while everyone else catches fish with lines and spears. When a fire is lit and the air smells of cooked trevally, we talk as casually as men at any barbecue but Gurriwiwi is revealing important matters: initiation, ceremonies, songlines.

I ask him to play "the dolphin" again. He obliges and it's raw, unearthly and I want to learn it more than ever.

"How old is the song?" I ask.

"Very old. Unbroken. Long time back, now and in the future. Travelling long way."

That evening I take Soh to Nhulunbuy's Walkabout Tavern where "toppies" - topless barmaids - are stripped to their G-strings. We buy beer, sit among miners and eventually stop noticing tits.

"Djalu is very ... ah ... famous among Japanese yidaki players," Soh says. "I am so happy: I hear Djalu and I touch ... culture." Soh's generous nature, the way he has embraced the experience and the family, makes me feel shabby. It's only later that I learn "Mr Didgeridoo" is one of just two traditional owners of yidaki knowledge in Arnhem Land.

I spent three days with a law lord of the world's oldest instrument - and I didn't know it.

Seven Emu Station The hand-painted "Beware of the Croc" signs at remote Seven Emu Station are not for show. Six-metre salties gorge on fish in the Robinson River as it slugs into the Gulf of Carpentaria south of Borroloola. The week before I arrive, a croc took a saucer-sized chunk out of the face of a grey gelding as it bent to drink. "I've packed the hole with lime," says stockman Frank Shadforth, soothing the skittish horse, which some graziers would have shot. "He'll be OK."

Shadforth owns a 40-kilometre stretch of the little-visited Robinson River, as well as 100-metre river cliffs that glow ruby in the sunset. He also owns 75 kilometres of beachfront washed up with shells and dugong bones, a beach almost brutal in its isolation. And he owns the 200,000 hectares of tropical savannah where he raises 2000 Brahmin cattle.

"Not lease," he says. "Own."

He makes the point for good reason: Frank Shadforth is Aboriginal and, as he says, there aren't too many Aboriginal station owners.

His father, Willy Shadforth, a full-blood Garawa man, was a stockman who saved hard. In 1953 he backed a Caulfield Cup winner and put the winnings on a Melbourne Cup horse. "That won, too, so he bought Seven Emu Station. My father was a very cultured man - respected - and he lived both ways. But he'd had a hard life and didn't want the same for me. He said to me, 'You can go blackfella way, or white man's way."

' Shadforth junior was sent 90 kilometres to Borroloola by horseback and from there to boarding school in Alice.

Today, he doesn't speak the indigenous language. He doesn't gamble, drink or smoke. He does, however, have a twinkling sideways glance and is amused that his six volunteer "woofers" - Willing Workers On Organic Farms - have turned out to be pretty young things from France and NSW.

"No, I didn't ask for them, they just turned up like that!" he says. "But I reckon they could be really useful for the tourism."

The young women work with Aboriginal stockmen to fence paddocks but will soon be helping to build dunnies near the river cliffs, five kilometres from the Seven Emu camp.

Having swagged in one of three campsites - a lofty dell of colitris pine with a hawk's-eye view of the river - I can tell you this is priceless country. And as of this month, it is all available for about $10 a person a night. A development officer from Tourism NT has advised Shadforth to keep it simple: long-drop toilets, a basic shop, campfire nights serving stockman's tucker, tours of the property.

"Keep it simple," Shadforth muses. As we tour the river, beach and mangroves, he tells tales of cattle-duffers and crashed World War II airmen and shows us his birthplace - a billabong fringed by mango trees.

The day ends in a protected river-braid on the Robinson where sunset falls through corkscrew palms. We lark about in rushing water and get clean before dinner.

The camp is "old school" - corrugated sheds over beaten-earth floors, trestles, country music. Stockmen, woofers and Shadforth's family load up their plates with rib-eye curry and flatbread "johnny cakes", then Shadforth's daughter cooks turtle in hot coals. Cheeky kids show us how to pull choice bits from the upturned shell and we all try it: an oily, pungent version of lamb. Shadforth sits by the campfire, casting his twinkling sideways glance. "Keep it simple," he repeats. "Keep it simple."

Bawaka Cultural immersion gets real in Bawaka, a traditional homeland an hour's drive south of Yirrkala in Arnhem Land; a place where you might find yourself carrying a live shark in a bag slung around your neck.

It's where Balanda - white people - sit down with Yolngu people. Most visitors are from mines or government, sent here to learn; others are tourists. And everyone loves it: the three simple shacks on a sizzling white-sand beach, the breeze off Port Bradshaw that causes the palm fronds to hustle and shiver. These are the lands of the Burarrawanga family, including 50-year-old Djali, a Gumatj man.

Ben Wheatley, a 22-year-old whitefella, helps with the guests. "You could say I'm Djali's apprentice," he says. "He's teaching me Yolngu language, fishing, kinship." After an intense year with the family, Wheatley says he's barely scratched the surface.

On my arrival at the camp, Djali performs a smoking ceremony. "You are being watched over by Bayini," he says, brushing me lightly with smoking leaves. "Now you are protected." He's serious about Bayini, the spirit woman of Bawaka and the ancestors who strode out of the dune country behind us to create the world. I'm told not to go near or photograph the giant dunes.

Next I must meet the family matriarch, Laklak, who sits with her young family in the shade of palms. A shrewd, no-nonsense woman, she welcomes me and explains that Bawaka is a place of exchange and understanding. She explains that she takes women guests to gather and dye reeds then weave story, culture and sisterhood into baskets. Men, however, have other business.

A large group of us drive five kilometres along the beach to a point where slow currents swirl and mash. Men disappear into the mangroves with spears for mud crab but Djarli instructs Wheatley and me to unfurl a 20-metre net, like a fenceline, in-waist-deep-water. He reads the water, focused, then barks orders at Wheatley in Yolngu: Be quick, secure the net with spears!

Bang! A dozen mullet - thumping silver bars - hit the net, causing it to spasm. The strong fish are snared up to their gills and in the frenzy of harvesting I appeal to Wheatley for help. "Hook a finger into its gill and watch the spikes!" he shouts, loading fish into a supermarket cooler bag around his neck.

Wary of gills and spikes, I end up snapping off a fish's head. "Don't do that," he says, handing me the bag, "the blood will attract the sharks."

He's right. A half-metre shark is soon netted and gingerly dropped into my bag, where it flexes furiously. The second shark is a 2.5-metre marauder - black fin slicing slowly through water about 30 metres away. Djali repeatedly stabs the sand with his spear. "Tells him I've got teeth, too ..."

After three hourswe have 10 kilograms of fish. This includes a stingray that won't die at the point of Djali's spear; while the animal is pinned underwater, he takes the whip-like tail between his teeth and knocks the barbs from the base using a club. Disarmed, it's hoisted back to the beach like a parasol.

The night is spent around a huge fire on the beach, where Djali explains that the mullet is at its best. "Yellow flowers are on the wattle - means there's a layer of fat under the skin, better eating." Guitars are strummed, jokes are told and a "pet" crocodile crawls from the shallows to snap up tossed scraps of fish.

Next day, Djali says I'm fishing again, "properly this time". "Properly" means walking the five-kilometre beach, carrying our gear in the hot sun. I learn to spear, I learn to read the currents, I cook and eat fish to maintain energy. And when the sun sinks low, the 2.5-metre shark returns - and scythes our net to shreds.

I've never experienced anything like it and I'm not entirely sure I'm in Australia.

Max Anderson travelled courtesy of Tourism NT.

FAST FACTS

Getting there Virgin Blue flies to Darwin non-stop fromMelbourne (about $149). Qantas flies non-stop fromSydney (about $240) , as does Jetstar (about $169). Tiger Airways flies from Melbourne only for about $100. Qantas flies fromDarwin to Nhulunbuy for about $280. Fares are one way including tax.

Touring there

- Rripangu Yidaki masterclasses cost $300 a person a day. This includes hotel pick-up from Nhulunbuy on the Gove Peninsula, yidaki tuition and yidaki-making. A program of five-daymasterclasses is available; see rripanguyidaki.com. To book day classes, phone 0447 087 091.

- Cliff camping at Seven Emu Station is now available for $10 a person a night. Seven Emu Station is 90 kilometres south of Borroloola, which is 1000 kilometres south-east of Darwin on the SavannahWay Highway. The road to Seven Emu Station is accessible for four-wheel drives and campervans and requires a (usually) shallow river crossing. Visitors need to be fully self-provisioned for camping but check developments on sevenemustation.com or phone (08) 8975 9904. Closed in November.

- The two-day Bawaka Cultural Experience includes all food, a swag and transfer from Nhulunbuy. It operates all year. Phone 0447 087 091, see bawaka.com.au.