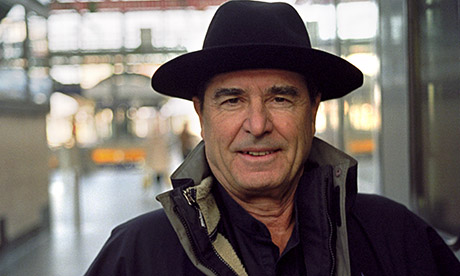

Travel writing giant Paul Theroux talks to Peter Moore about his latest African adventure. And why it may well be his last...

The influence of Paul Theroux on travel writing as a genre cannot be underestimated. Where Bill Bryson showed that it was OK to be funny, Theroux proved that you didn’t need a grand quest or goal in order to write a compelling travelogue. You didn’t need to set off in anyone’s footsteps, you could simply take a journey and write about the places and people you encountered. You could be a legitimate and credible witness to a particular time and place.

He also wrote one of my favourite passages ever about Australian travellers. It’s in The Great Railway Bazaar, on the Van Golu Express in Turkey, and he found himself in the company of three scruffy Aussies.

I always liked to think I was marking the bottom for others in my travels.

Having said that, when it fell upon me to chat to Paul Theroux about his new book, Last Train to Zona Verde, an account of an overland journey from Cape Town to Angola, I approached the actual interview with some trepidation. Theroux has a reputation for being prickly and not suffering fools lightly, so I started by saying how much I enjoyed that line about Australians.

‘It was a joke!’ he laughed. ‘I’m glad that you got it.’

Not prickly then. Just misunderstood.

You begin this trip with a real sense of foreboding. I was wondering why that was and whether it was a good idea starting a trip feeling like that?

The best way to write about travel is to be truthful. It’s not a question of whether it’s a good or bad idea. If it’s the truth, if it’s the way you actually feel, I think the reader trusts you. To create a false sense of bonhomie is wrong. You need to level with the reader. I think if a book is written well, it doesn’t matter what trip you’re taking the reader on, as long as you’re telling the truth you’re doing the right thing.

Why did you take this particular trip?

The way I’ve taken every trip, particularly for a book, is out of a deep sense of curiosity and a deep distrust of the Internet and second-hand stories. I wanted to see for myself what had happened in Cape Town in the ten years since I wrote Dark Star Safari. It had seemed to be in a transitional phase. I’d always wanted to see the San people, the hunter-gatherers in Namibia. I’d never been to Namibia. And I had always wanted to go to Angola. Angola was really off-limits for almost 30 years. So, the shorter answer is curiosity and an interest in these particular places.

Do you think your trips are as serendipitous as they seemed in the old days, where you started a journey and just let it take you wherever?

They’re not always serendipitous. I think you have to be lucky. But if you have enough time to travel and you put the effort in, things happen. You need to be patient. You can’t take a two-week holiday and expect great things to happen.

Are you taking the same risks you used to? You seem to be having an ongoing debate with yourself in the book about how far you’re prepared to push yourself.

I think I took the same risks and was as uncomfortable as I have ever been. And I resolved myself to travelling overland. Nothing is more uncomfortable than vowing to go overland. You end up in old buses, trucks, taxis or old beat up trains.

In terms of risk, I didn’t avoid any places, but I got to the end of my tether, if that’s what you’re asking. There’s a point beyond which I’m not willing to go. I’m not willing to take a ten-hour bus ride to a place if I’m not going to learn anything, if it’s going to be exactly like the place I just left. When you’re going from one African city to another, you find just an urban sprawl. What’s the point of being there?

On this trip, you seemed to have the most memorable experiences when you got off the beaten track. I’m thinking in particular of that village you got stuck in because the truck broke down.

That chapter (Three Pieces of Chicken) is one of my favourite chapters in the book because it was serendipitous. I’d got to this place that seemed to be nowhere, in the bush, and something happened. Then there was the symbolism of the three pieces of chicken. Someone offers you a disgusting piece of chicken and you say, ‘I don’t want that’ and that ends up to be the only meal you’re going to get. So you take it.

So that was really a wonderful experience but it was lucky. People were saying to me, ‘Don’t go by road in Angola, the roads are terrible. You should fly.’ My response to that is, if you fly you’re not going to see anything. You’re just going to see the airport and you’re going to get, more or less, special treatment. The people I know that have been to Angola, that have flown there, have a totally different impression of the place that I do. I feel as though I’ve seen the heart and soul of the country by just going down the bad roads.

On that point, later in the book, you dismissively describe West African cities as the ‘Africa of rappers and cell phones’. With music often offering a way out of poverty and Africans using emerging technologies in new and exciting ways, surely it’s a side of Africa worth investigating?

I do think there is something to discover there. I think you could make a subject out of the new music or the way they have adopted rap music and graffiti and cellphones, but it’s not for me. Those subjects don’t interest me at all. In fact they repel me. If I was interested in that, I would be writing about rap, graffiti and cell phones in the States, where I live. But I’m not interested in it. I’m interested in, more or less, traditional culture and I travel for freedom, to discover something in myself.

I find cities nasty and repellent and African cities particularly nasty. So I try to avoid them. But another person, with the right disposition and who cares about such things would find a lot to discover. But I don’t have any interest.

What does interest you?

I’m more interested in the hinterland. I like travelling in the countryside, in country areas, in the middle of a place, not in its urban centres or cities. That’s why if I went to China, I would avoid Shanghai and Beijing, I’d go to the west. I was in Kunming in 2007 and I felt I didn’t want to be there.

Also, as a traveller, it’s a bit easier to understand places in the countryside, for their simplicity. It’s easier to write about a town than a big city because it is more graspable. A city has an inherent incapacity to be known. And so you can’t really write about a whole city.

In the early 80s, I wrote about the subway in New York and that was kind of interesting. But I really have no interest in either going to New York or writing about New York City. You say that to a lot of people and they say, ‘Oh, God, that’s where all the life is.’ I’d be much more interested in going to rural Alabama or the Mississippi.

In the book, your happiest moments are when you are in the far north-east corner of Namibia, with the Hu/Joansi people. There’s a lovely little scene where you are quite literally following in their footsteps, chasing the dust flicking up from their feet. You seemed almost joyous.

It’s a bit of a charade actually, because they are sort of reenacting – reenacting their lives as hunter gatherers. But still, for the period of time that I believed it was real, I was happy, yes.

You say it was a reminder of our better, ancient selves. Is that nostalgia or can we really take something away from the way they live?

It’s both. It’s nostalgia and I suppose, kind of enlightenment. But a lot of travel outside your own country is nostalgia. I was in Sydney, for example, and I went by bus to a suburb. I was staying in a nice hotel on the harbour, but I was waiting for a bus in an outer suburb of Sydney and I thought, ‘This is like the town I grew up in 1950-something.’

I just wanted to have a quick chat to you about your visit to Abu Lodge (a luxury safari camp). It seemed like a very unlikely thing to do. What was the idea behind that?

Africans never go on safari. So travellers to Africa often see an Africa that Africans don’t see.

I knew the guy who ran Abu Lodge. His name is Michael Lorentz, and I thought, ‘He’s passionate, a defender of elephants, a preserver of the bush.’ He has this very expensive lodge in the Okavango Delta and I had never been to the Okavango. I figured, in a way, staying at such a lodge was seeing the Okavango at its best.

So I went to show the kind of experience that a wealthy person would have of Africa, which is utterly unlike the experience that your readers would have. They’d be hitch-hiking or taking an old Land Rover somewhere, travelling through Namibia or Angola or other parts of Botswana. It’s to show a contrast between the kinds of experiences that a person would have if they had money and so they see something that most travellers in Africa don’t see.

I felt that at the end of that chapter you swung it right around. It felt almost like a metaphor for Africa in that you can try and impose these temples of dreams but Africa always seems to claim back its own.

I’m not sure what you mean.

Well, it seemed like it all went wrong. There was this beautiful, expensive place and then poor Nathan was killed.

In a way, it’s doomed to fail. The idea of having this super luxury camp in the middle of nowhere, stocking it with wine, is futile, really. People do it. You’re asking for trouble though.

I was also struck by how many people died over the course of this trip.

Yes. Three people that I met died.

Actually, it’s four. You visited Vicky’s Place in Khayelitsha, the township B&B. A couple of months later Vicky was murdered by her husband.

No. Seriously? Is that right? She was funny. How do you know her?

I stayed there about the time you were doing Dark Star Safari. I did the same trip as you except I went from Cape Town to Cairo. I think we crossed paths in Nairobi. Do you remember that German film you wrote about? I was an extra in that.

No. Really? Where were you? I thought they were making it in Nyeri or somewhere?

They did. But they shot some scenes in Nairobi, in a boarding school. I was playing the part of a German prisoner and we were all in this sort of intern camp.

What was it called? Something like Africa is Nowhere?

Nowhere in Africa. And it won an Oscar for Best Foreign Film.

No kidding. I didn’t know that. Were you on screen?

I was. You need a very steady finger on the pause button, but you can spot me about four times.

By the way, it’s a great title, Nowhere in Africa. It’s a great title. So when was Vicky murdered?

About three months ago. If you Google it, you should be able to find a news story.

Oh man, that’s terrible.

Is death more prevalent in Africa now or were you focused on it because you felt this could be your last journey there?

I’ve had a lot of friends who have been killed or have died in Africa over the years, for various reason, going back to the 60s. So you’re very aware of the fragility of life in Africa and also, of people dying young. Life expectancy in Africa is very low. In some countries it’s in the 30s. In Zimbabwe and Zambia it's 36 or 37.

So there’s that. And then there’s the fact that in many cases the roads are bad, buses are poorly maintained, too crowded. Car crashes in Nairobi are quite frequent. These matatus [privately-owned minibuses], they’ve got too many people in them and they drive too fast. So I think that more than any other place, you’re aware of how fleeting life is and how you’re at risk in a lot of forms of transportation.

But that didn’t stop death being shocking on this trip. I didn’t expect a 40-year-old guy to have a heart attack, or this fellow I met in Angola to be bludgeoned to death in his own home. And then there was Nathan, a guy who knows all about elephants, and he’s crushed to death by one. You don’t really expect that.

And yet, it happened. I hope the book isn’t morbid as a result. But it did make me think, if I push my luck, I may be one of them. When you leave home, and you go on a long trip, you think you might not come back, but this really set me thinking. It made me less confident. And sad, too.

Were you expecting Angola to be as crazy as it was? Your friend, Kalunga, says, ‘This is what the end of the world is going to look like!’

I didn’t know what to expect, but I didn’t think it would be quite as difficult as it was. I thought the cities would be somewhat negotiable. They’re not. They’re big and horrible.

The assumption you might make about a country that pumps two million barrels of oil a day is that some of the money is going to trickle down and the schools won’t be too bad. The schools are terrible. The roads are terrible. The people are demoralised. The government is corrupt. You’ve got to see it to believe it. If you look at Angola on the Internet you might think that it doesn’t look too bad.

Having said that, I’m not dismayed when things are awful. It gives you something to write about. If it’s just great food and hospitality, there’s not much to report except that you had a good time.

When did you realise you weren’t going to continue on up to Mali, that you’d reached the point that enough was enough?

When it became clear I’d have to fly some of the way. I could have hopped around, taken my chances. But I really wanted to make a continuous trip. You get to a place and you say, ‘How do I get out of here?’ There’s a train, there’s a bus, and you go to the next place and then the next place and the next place. But I couldn’t do that. There were riots in Kinshasa and problems in Nigeria and Mali. So when I realised I wasn’t able to make a continuous journey, that I would be forced to fly, well I thought, this is the end of my trip, I’ve really come to the end of the line. It’s not a difficult decision. It’s just saying I can’t go further. And that’s that. End of the book.

When you first started travelling, you say that what drove you to travel was the notion that the real world was elsewhere. Do you think that today’s young people, who think that the world is at their fingertips, need, more than ever, to get out and see the world?

Yes, I do think so. The idea of depending on the internet for information, to think you can have this experience by Skyping or Google mapping, and you somehow experience a country, is all wrong.

For one thing, the Internet is full of misinformation. It’s full of opinions, not facts. The idea that you’re going to accept these opinions and that you don’t really need to travel and you will know about a place by reading about it rather than going there is ridiculous. You’ve got to leave home, you’ve got to go and see the world for yourself. And the important reason is to find out who you are, what your fate is in the world and what you can do with yourself. You have to get away from your family, you’ve got to get away from your home town, your city and make yourself uncomfortable and lonely and find out what the rest of the world is like. That’s very important.

You’re not necessarily going to add to the happiness of people, even if you do volunteering work. It’s nice to think you might make a difference but you probably won’t make a difference at all, except to yourself. You will discover who you are and what the limits are of your patience and your resourcefulness.

At the beginning of the book, you state that you feel the trip would be in the nature of a farewell. Was it a farewell to Africa? A farewell to travelling?

To Africa. When I started off in Africa 50 years ago, I was a teacher in a school in Malawi. I thought I might make a difference. Then I saw the fluctuations of the fortunes of the country and I realised I couldn’t. I’d seen it up and down and down again. I don’t think there’s anything more I can learn travelling in Africa.

It’s not a farewell to travel at all. As a matter of fact, a week ago I was in Alabama, travelling around the deep south of the USA. It’s a different type of travel. I’m trying to find something out about my own country. I’m not interested in just sitting at home, either writing or watching television or tending my garden. I need to get out and like to get out.