We ended up spending the night with Ali in his apartment in Giza. Taking another mini bus to the city center, I watched the Pyramids disappear under

the urban sprawl of Cairo. Once we reached the city center, Jess, Tony and Ali stepped out grabbing our bags. I was on my way to the vast barren desert of Sinai.

Ali, our Egyptian friend had given me some advice on getting to my destination, told me what bus I had to take. I was going solo from here. Standing on the sidewalk with my backpack, I watched the cars on the street pass each other and swerve in and

out of lanes like racers at a flat track, throwing no caution to pedestrian safety or their own lives, for that matter. The street was piercing with loud noises as

cab drivers yelled at mini bus drivers. Bus drivers honked at people crossing the street – an urban chaos.

I expected to need a cab to get to the bus station in time, what I didn’t expect was Ali walking into the torrent of traffic, sticking out his arm at a

cab barreling down the boulevard at 40 miles per hour in front of him. Remarkably, the cab stopped just short of his pot belly. “Yes, this one, you get in,” said Ali

before instructing the driver where to take me. “Yes, get in, must hurry.” Ali took my bag, threw it in the open window of the back seat like Mr. T at a midget toss,

then hurried me into the cab and closed the door. I didn’t have any time to wave goodbye to my new friends Jess and Tony, with whom I had shared such an amazing day. Cairo is a fast town and no one takes the time to stop for anything except for prayer, tea and hassling tourists. Ali was different, he was a big help,

now a good friend.

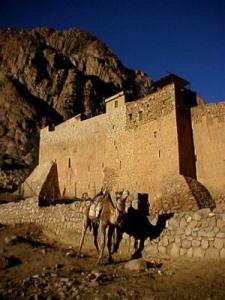

Monastery of St. Catherine, Mount Sinai

Monastery of St. Catherine, Mount Sinai

I arrived at the East Delta bus station shortly after 10:00 am. I was on my way to the Monastery of St. Catherine, in an isolated village, smack dab in the middle of the rugged Sinai Peninsula. Sinai is famous for the biblical odyssey of Moses, when he led his people through the desert for 40 years. At 10:30 am my bus left. The coach was ensnarled in stop and go traffic. Cairo has become the heart of Egypt. If its many roads and highways are its veins and arteries, Egypt has some serious circulation problems. Picture the kind of traffic when you leave the parking lot of a major sporting event. It’s like that times a thousand – gridlock

in all directions, honking, drivers yelling at one another. I enjoy seeing humanity in chaos, but not when I’m sitting in the back

of a bus without air conditioning wedged between Ali Baba and Hodgi Bonagi.

It took 2 hours to just get out of Cairo, but I was on my way. The desert outside of Cairo was a veritable wasteland, rocks and sand as far as the eye could

see. Stretched out across the horizon were miles and miles of eclectic wire, although there was not a sign of animal or human life. There was litter and garbage, though. In 4 hours we hadn’t gone more than 100 kilometers. The bus stopped every 5 minutes for some reason. Someone had to go to the bathroom, the driver wanted a smoke, a dude wanted the driver to pick up his cousin 5 kilometers out of the way down a dusty

road. No one but me was concerned about making good time. It’s hard for a westerner to stay open minded in a predicament like this. I had to remember that this part of the world moves much slower, on

what is famously understood as Egyptian time. The concept can be converted to most any third world country. Zambia time, Cambodian time, Morocco time. The idea is that although most Egyptians are poor and have few commodities. The one thing that everyone has is excess of time, – inshala, no second is unused, if possible.

Occasionally the bus would pass a speck on the side of the road, a satellite village where someone came aboard, cramming their way in. The area was littered with trash and rocks. I thought this place would be a primo spot to test nuclear weapons. The bus passed

countless armored vehicles along the highway. There were military camps farther off the road in the desert. APCs, tanks, a platoon of

Egyptian troops passed my window. Either the Middle East was in one of its classic wars to oust the Jews from their promised land, or the Egyptian army was playing war

games.

Because of the military presence, there was increased checkpoints. At one of the armed checkpoints, soldiers walked quickly

around the bus, checking underneath with mirrors, searching for bombs. I saw a stoic, flashy young solder standing at attention by a guard

station – my chance to pretend I was a war correspondent. I took out my small digital camera, pressed the shutter button. Three soldiers came marching towards the bus. The first soldier rapped his fingers around the handle of his pistol. I knew they were coming for me. Two of the soldiers

climbed aboard, despite a verbal protest from the driver. They pushed their way through the crowd (many of whom had been on their feet for hours).

I went into tourist mode: headphones on my Ipod, opened the first page of my travel guide, wore a baseball hat I

had buried in my bag – the idiot tourist. The soldiers reached the back of the bus. The

leader, still with his hands on his gun, sternly asked me for my passport. I surrendered it. His face displayed a sense of concern about the fact

I was an American. He turned to the other soldier who motioned for me to get off the bus and pushed me toward the front of the bus. I was led passed other soldiers, clustering in a group smoking cigarettes, laughing at me. They took me to a small building across from the checkpoint. I didn’t

speak, but I remained calm. It was understood I had goofed, although I had no idea what was in store for me.

At that time I was working for the Department of Defense as a ski instructor (that’s a different story); I had a military ID. I began thinking of a painful and torturous future. Nothing seemed impossible at this point. The building I was in was hot and musky, paint was peeling, the floor was solid concrete with a small drain in the

center, probably to wash out the blood from the victims whose heads got chopped off for taking photos of military installations. There was a small desk in the center of the room with nothing more than a pen and a single piece of paper. Led to the desk, I took a seat on a small wooden chair.

I couldn’t believe

what was happening. I was in the middle of the Egyptian desert, at a armed checkpoint, detained. Soldiers guarded me clutching AK-47s. Did they think I was John Rambo. I knew the crime: taking photos of military

personnel at a checkpoint. Despite my fear I insisted on trying to humor myself. I

began issuing a number of stupid questions at the man on guard. I went as far as to ask him how many times he had seen Star Wars and what his favorite brand of catsup was. He remained at his post, standing silently showing no expression. An officer walked holding my passport. He flipped through the pages examining my visa. His green uniform was wet under the arms; he had a musky scent about him. His black hair was slicked back with oil; he had a mustache like the kind you see on mug shots of pedophiles.

The officer asked for my camera. I handed it over expecting never to see it, or my photos again. He reviewed my photos quickly, asked me to delete the ones he didn’t approve of, ones like the lovely shot of the soldier who got me into this mess in the first place. To my relief and surprise, he was satisfied with looking over my photos. He handed me back my camera, along with my passport, and walked me to the door with all my all my limbs attached. The bus was still waiting for me. I learned a valuable lesson that day.

The bus ride was long. I watched the sun sink behind the jagged rocks and cliffs of Sinai, fires beginning to spring up in little huts along

the road, the hot suppressing Sinai sun give way to a cold, moonless night. Most of

the shanty houses in the villages were without electricity. More checkpoints. The men and women who live in

this difficult land are nomadic people, rugged and hardy, people who made war across the Arab world, alongside the profit Mohammed, claiming lands in the name of

Allah.

When the bus pulled off along the side of the road, I collected my belongings and cast myself into a dark and unfamiliar world. I could only see a few dimly lit buildings in the distance. The driver walked off the bus, closed the door before vanishing into the darkness. I put on a light

jacket, threw my backpack over my shoulder. There were no hankers or touts at this

late hour – just me and my backpack

Walking down the dark road, I saw the lights of an open café sitting isolated like a star in a distant galaxy. After examining and scrutinizing me, the men inside welcomed me in Arabic and broken

English. I had a cup of Nescafe and a plate of food. The owner suggested I not walk in the dark, but I felt he simply wanted to sell me a room (at his brother’s). I was determined to be at the top of the monastery by

sunrise. With only a flashlight, I navigated my way a mile before I

could see the fortress. I walked to a gate guarded by several out-of-uniform police. Suspicious, they went through everything I had, unrolled my sleeping bag,

questioned me about every article in my possession. Satisfied, they let me pass through the gate.

I was now on my own. Beyond the walls of the monastery. the earth rose into the sky with formations of rock that gave the setting an eerie feeling of being on a newly discovered planet. High above my

head was the holy mountain where Moses is believed to have delivered the Ten Commandments. Although I never considered myself religious, if the stories of the bible are true, I was walking

in the footsteps of God, would have to be careful not to step on his heels.

I began the climb; the air was

silent, the calmness of the earth dreamlike. No sound. After an hour of hiking, I caught my breath, took a drink

from my pack, sat wedged between two rocks. The stillness remained unbroken – an absolute silence that was defining. I could hear the beat of my heart – an altogether frightening

and peaceful sensation.

I drew near the summit. Without the protection of the mountain the wind picked up, the air was much colder. I was 50

meters from the top when I found a place between two rocks to shelter me from the strong wind. I climbed into

my sleeping bag and waited for dawn. Just when I was at my most uncomfortable, I heard approaching footsteps moving over the rocks. Careful not to make a sound, I

remained still. The footsteps moved closer. A few moments

passed. I opened my eyes and moved my hands closer to my knife. Then a flashlight illuminated the ground around me. I jumped up, nearly tripping over my sleeping bag. Whoever it was turned away and started walking up over the rocks. I stood motionless as the man walked along the rocks above me. He stopped again, shined the flashlight on my face and said, "Come, you go higher. Much cold here, you come with me, we make fire."

"Speak English yes, come with me, I am Muhammad.” I followed Muhammad into a small cave. The walls were dressed with blankets and sheets. In the center a dying fire crackled. From the top several

lanterns hung some dripping with oil. Lining the cave were several cardboard boxes containing supplies. Muhammad suggested we have tea. He grabbed an old radio and tuned into some music. I could not tell his age. He didn’t pay much attention to me until after I removed my boots.

Thanking him for taking me in, I introduced myself, we began to talk. When I asked why he was living in a cave on top of a mountain, he said he had been in the cave for a number of years making small crafts to sell to people who hiked to the top. He came from a small village in Sinai. He was raised to be a shepherd, but one year his flock was killed, he had no money to

buy more goats. When he decided to sell crafts at the top of the mountain, he had to hide because it was illegal. If

he were caught, he would be thrown in jail.

“Life is lonely,” he said, but stated he was happy. “If Allah wishes I will go to jail, and if Allah wishes I will die here. It is like this, it is all

in the hands of God.” He remarked that he loved the mountain. He was born in the desert and the desert was all he knew, he liked the way he lived,

that’s how his people lived.

Mt Sinai at dawn

Mt Sinai at dawn

Mohammad asked me to hold out my hand. "You see, each one of your fingers is different, this one is smaller than the other, one is fat and this one is long. All the fingers are different. but look, they are part of the same hand, like people. This is how Allah sees all things." I finished my tea and closed my eyes. Muhammad promised to wake me before sunrise. When Muhammad woke me, I stepped out and went up the last few steps to the summit. where there was a small church. I looked out across the landscape. I was not alone. I had a few minutes to myself when I saw a line of tourists heading up. I could see all the way across the Red Sea, into Saudi Arabia.

I started working my way down towards Muhammad’s cave. A group of Kenyans on a biblical tour came up singing songs, clapping their hands, some even dancing. By the time they reached the top, a sense of freedom overtook me. I felt like a king.

Muhammad had prepared tea when I returned to the cave to get my gear. We sat and talked for while longer before I went on. I will never forget this day.

This article is a continuation of Chasing the Pharaohs.