Are you an Irresponsible Traveller?

A peek inside new book The Irresponsible Traveller – celebrating the worst of travel's “d'oh” moments

New book

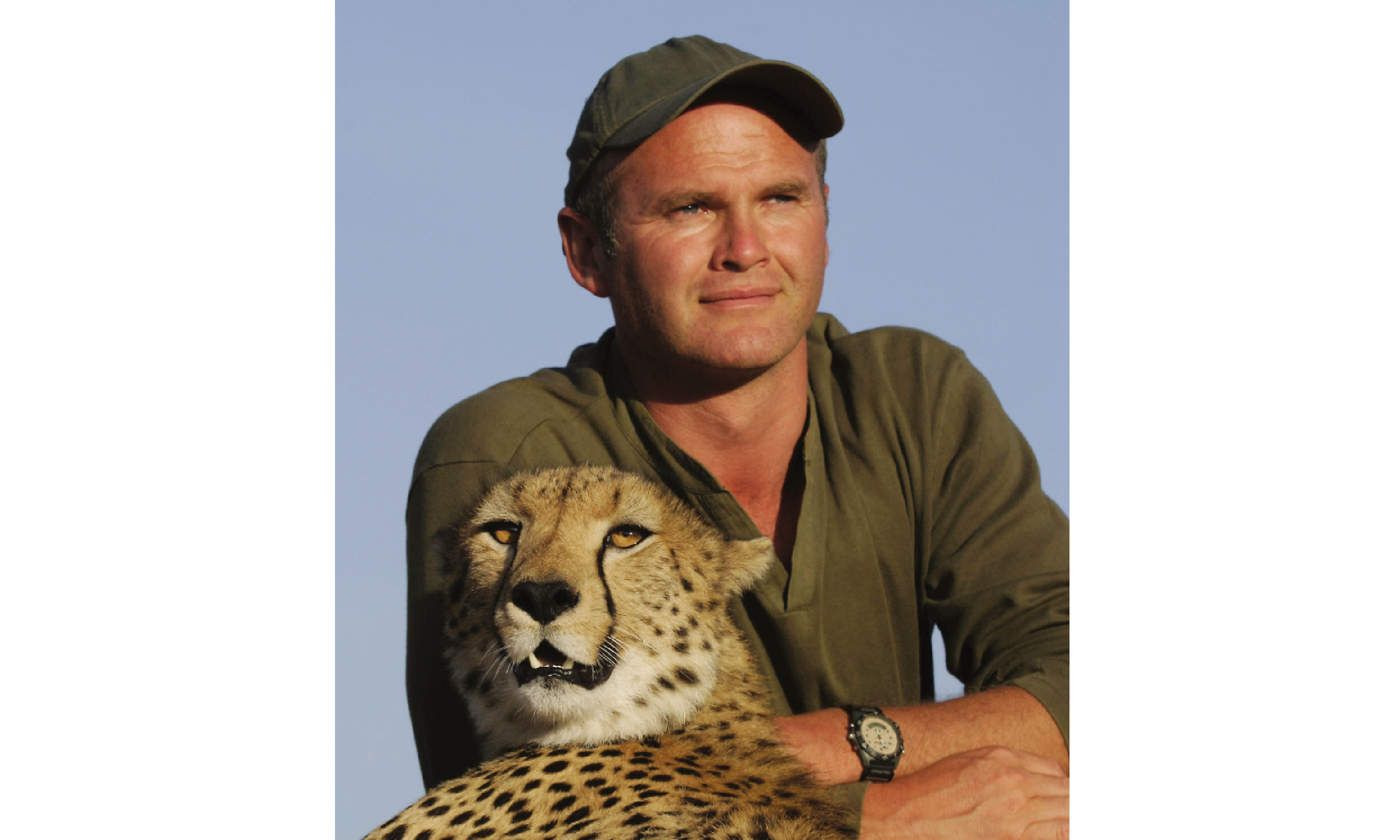

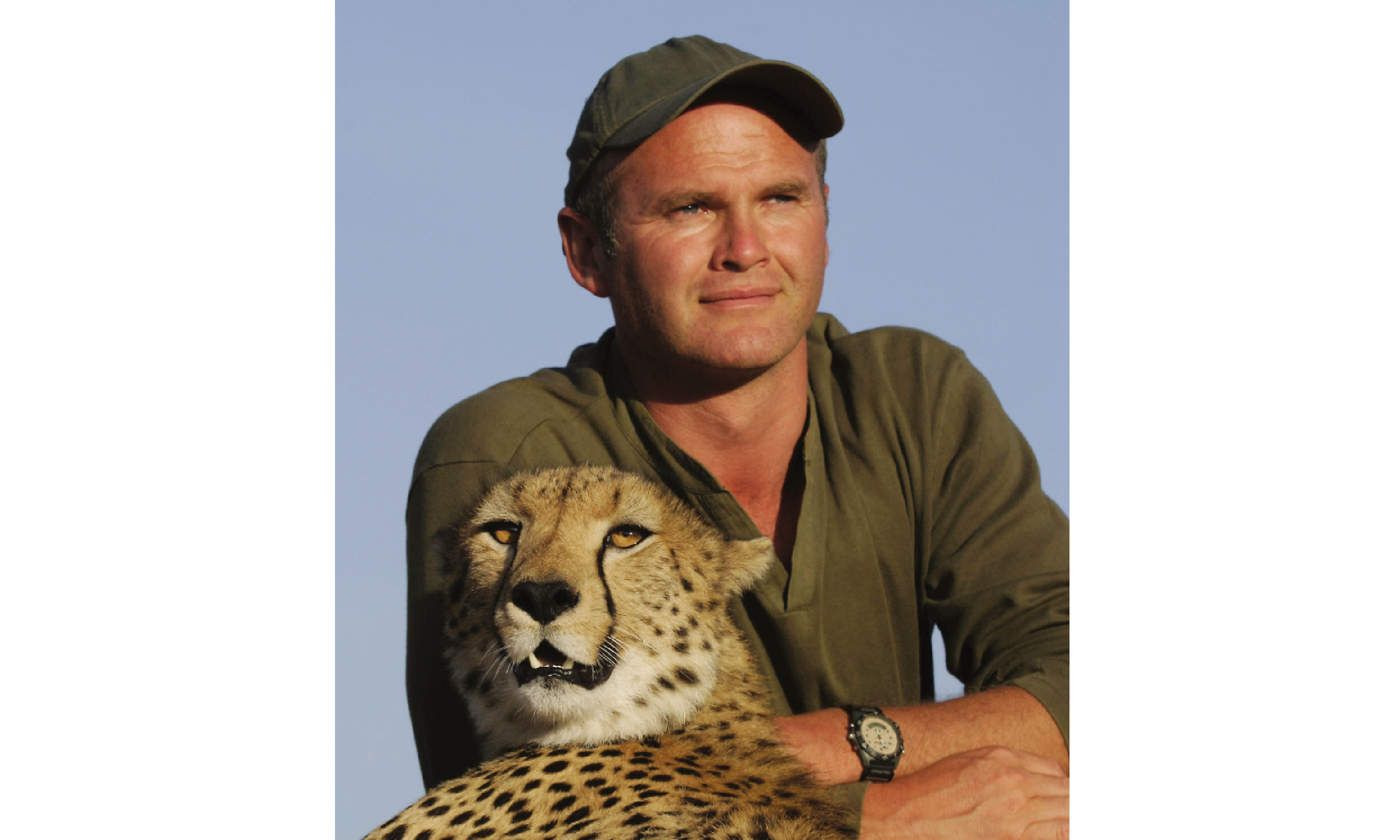

The Irresponsible Traveller honours the narrow scrapes and near-misses that even the most seasoned adventurers experience – indeed, the likes of Michael Palin, Dervla Murphy and

Wanderlust's Lyn Hughes and Phoebe Smith have all contributed to the book. Here, wildlife expert and TV presenter Simon King shares his most most toe-curling travel memory...

Want to read more? Buy the book here

Cheetah Attack

Wild cheetahs don’t attack people. A full-grown cheetah is significantly more powerful than a large dog, and many times better equipped to chase and kill prey up to the size of a wildebeest. Yet a long history of persecution from man and a naturally timid disposition means that this, the fastest land animal on earth, will run in the opposite direction if confronted by even a modestly built human being.

Hand-reared cheetahs, on the other hand, can present a few problems. With the fear of man diminished there is the potential for (and examples of) cheetahs using their speed, agility and natural weapons – a set of powerful jaws, long canine teeth and razor-sharp dewclaws – to inflict significant injury on people.

For several months they lived as an inseparable pair... Then disaster struck

This was one of many dilemmas I faced when, together with my wife Marguerite and a team of helpers from Lewa Wildlife Conservancy in Kenya, I took on the challenge of helping to hand-rear two orphaned cheetahs. From the outset, our aim was to release the brothers, whose mother had been killed by a lion, back into the wild. If this were to be successful we would have to ensure that Toki and Sambu, as they were known, were able to secure their own meals, recognise and avoid natural threats such as lions and, perhaps most importantly of all, fear man.

The last criterion was the most difficult to implement. The brothers had been bottle-fed from eight weeks of age and had started their orphaned life sleeping on sofas, running on a lawn with Labrador dogs and seeing people on a daily basis. Once we took over their education we tried to keep contact with new people to an absolute minimum, discourage contact with dogs and to introduce them to their wild world gradually with the constant protection of their human guardians watching over them at a distance.

Not all of it worked. There were times when the boys would run over to see a new human being they had spotted in the distance; and their first nights sleeping alone in the bush, when they had reached an age of almost two years, were fraught with dangers like lions on the prowl or hyena packs. Bit by bit though, they learned which animals were threatening (lions) and which they could easily outrun (rhinos), and their ‘bush knowledge’ was such that we were able to allow them the freedom of a 50,000-acre reserve.

The only remaining life lesson was to develop a fear of man, and this we orchestrated by positioning wildlife rangers, dressed in civilian clothing, in their territory. When Toki and Sambu approached, the rangers burst out of the bushes screaming, throwing sticks and clods of earth and chasing the bewildered brothers away. After a number of these ‘attacks’, the cheetahs became increasingly wary of contact with humans and started giving any they spotted a wide birth.

All of this was desperately hard to watch, but we knew it would be essential if the boys had a chance of surviving in the wild. And this they did.

For several months after independence, they lived well and contentedly as an inseparable pair, scent-marking their territory, and finding their own food. Then disaster struck. After eating a particularly large meal of an impala they had killed, the brothers retired to a rocky outcrop to rest and spend the night. In the morning, we visited the scene to check on their whereabouts and only spotted one of the pair, the male we called Toki. His brother, Sambu, was nowhere to be seen.

Toki was alone and without an important ally

We had put radio collars on both before release and the signal from Sambu’s led us to the awful truth: he had been killed by lions, like his mother before him. It was a tragic loss for all who had invested so much time, effort and emotional energy in his survival and release, but more importantly for his brother Toki, who now was alone and without an important ally.

To give Toki a fighting chance of survival we had to break our rules of limited human contact and once again play a pivotal role in his life. After several challenging months, during which he searched fruitlessly for his brother and almost died as the result of an attack from three mature cheetah males, we decided to move him from Lewa where he had grown up, to the nearby reserve of Ol Pejeta.

Now, instead of having free rein over the entire reserve, he was introduced to his new home in a 10,000-acre enclosure that included wild herbivores as neighbours, but not, to our knowledge, any other large predators. He was able to hunt for himself, but had little chance of coming into contact with either hostile humans or other cats that might try to kill him. It was whilst Toki was housed in this enclosure that an incident occurred that was so unlikely I, to this day, still wonder at the chances.

I received a radio call telling me that a cheetah was roaming around the outer perimeter of Toki’s enclosure. I assumed he had somehow escaped and sped over in my 4x4 to try and encourage him back into the safety of the fenced area. When I arrived near the main gate, I was greeted by a small number of Conservancy Rangers, among them Steven Yasoi who had worked closely with us throughout the rearing of both Toki and Sambu and who was stationed near the enclosure.

Steven immediately informed me that there was indeed a cheetah, but that he did not think it was Toki. I soon spotted the cat myself and could see at a glance that this was a stranger. It was sheltering in the shade of some cactus bushes, but I could see that, unlike Toki, it was not wearing a radio collar and it appeared to be smaller, more lightly built. After a short while this new cheetah got to its feet to find deeper shade and I could see that it was a female.

It was extremely confident near the car, and indeed paid no attention whatsoever to the small group of rangers standing and talking some 100 metres away. This was odd. If this was a wild cheetah I would have expected her to at least be staring at the men, and more likely running in the opposite direction. This is where I made my first stupid mistake. I assumed that this was also a hand-reared cheetah; that someone had got wind of the fact that we had a male cheetah in a large enclosure and had ‘dumped’ their cat on our doorstep in the hope that we would take her in.

From time to time, orphan cheetahs do come into the care of humans who, with all good intentions, rear them only to find that they are very boisterous and potentially dangerous – especially around children. It is also illegal to have a cheetah in captivity without a special licence. It was not beyond the realms of plausibility that somebody had dropped their troublesome cat at the gates of this potentially good home.

She ran at me and jumped up to try and bite

and claw my face and torso

In all the time we had spent with Toki and his brother Sambu over the past four years, neither one of them had ever been aggressive towards us, or any other human being, and it was with this in mind I made my second very stupid mistake. I got out of the car and decided to approach. Perhaps she would follow me into the enclosure gates, and provide Toki with a potential mate.

I walked gently towards the point where she was resting, talking to her the whole time. She turned to face me, then rose to her feet and gently walked in my direction. That clinched it for me – she must be a tame cheetah – and I spoke to her more clearly, saying (embarrassingly) “Hello sweetie”! I thought I heard her starting to purr – a trait uniquely reserved for cheetahs amongst Africa’s big cats, and a sure sign of contentment or appeasement. But something was wrong.

Her body language was shifting from a gentle walk into a head-down threat and I now could hear that the purr was in fact a low growl. And that’s when all hell broke loose. She ran at me and jumped up to try and bite and claw my face and torso. I instinctively raised my right leg and planted the sole of my foot into her chest as she jumped. Her dewclaw raked at my leg and her teeth sunk briefly into my boot, but the power of the kick threw her back a little and she stood before me, growling, before sidling off towards the group of rangers who were wisely making their way back to their vehicles.

I still believed she was hand-reared – this was, I thought, the only explanation for her complete lack of fear of man. I also believed she presented a real danger to other humans, especially children, so decided to keep a close eye on her and try to mobilise a team to dart her and take her into a holding pen for closer observation.

Steven followed her at a distance on foot, whilst I drove around ahead of her to try to prevent her from disappearing into thick bush country. By the time I reached the bottom of the small slope down which she had walked, she had launched an attack on Steven. I could see him struggling, with his thumb firmly grasped in her jaws. She then lunged at him, pushing him off his feet and clawing at his legs and chest. I saw red.

She lunged at him, pushing him off his feet and clawing at his legs and chest. I saw red...

Infuriated by the cheetah’s attack on my friend, I leaped out of the car, ran to the struggling pair and grabbed the cheetah by the tail and the scruff of the neck. She turned her attention to me, and tried to twist around to bite me. Luckily my grip was firm and the worst that she could do was to rake my forearm with her sharp dewclaw before I was able to wrench her from Steven and throw her as far as I was able in the opposite direction. I yelled at Steven to get into the car and I quickly followed him before the cheetah could gather her senses and return to attack again.

A dreadful thought now began to dawn on me. This behaviour, even for a bad tempered hand-reared cheetah, was completely out of character. It was, however, in keeping with the effect that rabies has on its victims. I had seen the tragic demise of hunting dogs to the ravages of rabies twenty years earlier, and shortly before their death they displayed uncharacteristic fearlessness and sporadic bouts of extreme aggression.

We waited for the ranger’s vehicle to join us and start tracking the cheetah before driving to a safe distance where I could tend to Steven’s wounds. I also radioed for a team to arrive to dart the cat, and before very long she was sedated and housed in a cage for observation. It was possible she was indeed just stroppy, but I had to be sure.

In the meantime, Steven was rushed to the local hospital to start a course of post-exposure rabies medication. I had received a vaccine some years earlier and, though the booster was overdue, I felt that I should keep an eye on the cat before heading into the hospital.

As she roused from the effects of the sleeping drug, it was clear she was not at all well. Her eyes appeared sunken, and a white froth was forming around the corners of her mouth. She chewed wildly at a plastic water container in her holding pen and then started biting at the bars.

I did not have the facility to kill her, nor would I have done so before dawn even if I had. I wanted to be sure she was not simply reacting to the confines of her enclosure. As it happens I did not need to. By dawn she was dead, a heavy froth around her gape, her pupils fully dilated.

By dawn she was dead, with a heavy froth around her gape

I immediately set off for hospital for my own course of post-exposure rabies medication whilst organising for the deceased cheetah’s head and brain to be sent to Nairobi for autopsy and diagnosis. The results came back about a week later. She tested positive for rabies. It was a tragic end for such a beautiful cat and an incredibly rare case. Rabies is rare at the best of times and when it does appear it tends to be seen in dogs and their cousins like jackals and hyenas. Solitary cats like cheetahs have rarely been diagnosed with it.

Several years on, both Steven and I are fine. But I shall always look back at this encounter, and the string of mistakes I made in assessing the situation as a very valuable life lesson: to err on the side of caution when dealing with magnificent, but potentially dangerous wild animals, and never allow assumptions to guide actions that may lead to myself, or others around me, coming into harm’s way.

Want to read more? Buy the book here

Simon King OBE, naturalist, filmmaker and author, was born in 1962 in Nairobi, Kenya. His love of wildlife began in Africa; his first career choice was to become an elephant when he grew up! At the age of only thirteen he teamed up with naturalist Mike Kendal to create a series of programmes entitled Man and Boy, his first foray into explaining the mysteries of nature to the general public.

He went on to create, film, direct and present many award-winning TV programmes and films, some of the best known being Springwatch, Big Cat Diary and the Life series plus more recently African Cats for Disney. Simon is closely involved with a variety of wildlife charities including being the current president of The Wildlife Trusts.