British Museum and African textiles expert Chris Spring on the importance of kangas in East Africa and the knack of wearing one correctly

Chris Spring is a curator at the British Museum and author of Social fabric: African textiles today. The book was published to coincide with the Museum's exhibition on African textiles. Here, Chris talks to Peter Moore about the history of the kanga and their social and political importance in East Africa.

When did you acquire the museum’s first kanga?

In November 2002 when I bought a kanga in Dar es Salaam. It was not made in Africa at all, but in Mumbai, India where it was machine-printed in a factory, rather than being hand-woven, dyed or embroidered. It was mass-produced specifically for sale rather than for any ‘ritual or ceremonial’ purposes. Indeed, there seems to be nothing about its design, or the colours and motifs used, which link it to Africa – or to any other part of the world for that matter; the only discernible connection is that the inscription it bears is in an African language, Kiswahili.

However, if you were tempted to think that this object was just a cheap, mass-produced piece of ephemera, a collection of black lines and coloured dots which could be used anywhere for anything by anyone, the inscription printed on it reminds you of your mistake: HUJUI KITU “You don’t know anything”.

What does the word, kanga, actually mean?

Kanga is the Kiswahili word for the guinea-fowl and presumably was so named because the spotted patterns on the early cloths were reminiscent of the markings on the plumage of this bird. The term leso is, however, still used in preference to kanga on the coast of Kenya.

What was the initial purpose of kangas?

By 1897, slavery was officially abolished in East Africa and printed versions of the kanga were being imported to Zanzibar from Britain. This was a time of rapid and fundamental socio-political change for many communities on the east coast of Africa, and kanga was one of the means through which increased wealth and social status could be reflected.

Are kangas still an indication of wealth?

Advances in roller-printing technology during the 20th century meant that the kanga could be mass-produced. Today most are printed in India, Kenya or Tanzania and sold in pairs to Swahili women who will cut them, hem them, and sometimes tailor them into dresses and other clothes. Although in a sense kangas have therefore gone from being an indication of high social status to a commodity which is much more widely available, the number, price and quality of kangas owned by a woman is still very much an indication of her status in society. Those printed in the mills of Urafiki and Karibu in Tanzania are generally of better quality – and correspondingly more expensive – than those imported form India.

How important are kangas?

These verses of the poem Kanga by Mahfouda Alley Hamid evoke the very special role played by the kanga in Swahili society, from birth to puberty, through courtship and marriage, to old age and death:

So kangas are used in different ways throughout life?

A new-born baby may be wrapped in an uncut and unstitched pair of kanga to confer prosperity, strength and beauty to the child and as a symbol of the parents’ love for their offspring. In this case the mji or ‘town’, the central space and design of the kanga may take on an element of the second meaning of mji in Kiswahili – ‘the womb’.

Young girls who have begun to menstruate will be given a kanga of red and black to wear; at their puberty ceremonies they will also give a kanga to their somo, a ‘ritual mother’ who has trained them in the requirements of adult womanhood. At marriage the bride will wear a special kanga of white, black and red, known as kisutu, which has a design consisting of three separate blocks of pattern, narrow borders and often no inscription, making it uniquely different from any other kanga.

Certain kangas, usually of the kisutu ‘crosses and tangerines’ pattern, are used specifically for praying in the mosque. These kangas are often those which have previously been used at the funerals of women to cover the corpse while it is washed, after which the kangas are sent to the mosque where their use by female worshippers continues to bless and honour the deceased.

Is the way you wear a kanga significant?

Kangas are also worn in different styles to suit particular occasions or moods. One style known as ushunqi is used when walking along the beach, with one kanga wrapped tightly around the head; at home this headdress is removed and is draped loosely around the shoulders.

When going to the market the style is known as kilemba, a name which derives from the turbans traditionally worn by Arab men, and refers to the way in which women wear the first kanga wound around their heads. Once at the shops or market the kilemba is removed and worn draped over the shoulder.

Muslim women wear the kanga in yet another distinctive style, with the first kanga arranged in such a way as to cover the head and, if necessary, the face.

Do kangas reflect changing tastes and attitudes?

The kanga very much reflects the changing times, fashions and tastes, providing a detailed chronology of the social, political, religious, emotional and sexual concerns of those who wore them. Those patterns and inscriptions also vary according to the age of the wearer and the context in which the cloth is worn. The inscription HUJUI KITU – “you don’t know anything”, for example, would usually be worn by an older Swahili woman to indicate her wisdom and experience, though on occasion a young woman might wear it to challenge an older woman’s authority.

Do the inscription on kangas give women a voice they may not otherwise have?

In the context of communication, particularly by women, there are interesting parallels between the development of kanga and of the style of musical performance known as taarab which accompanies important occasions in coastal East Africa and on Zanzibar in particular. Parkin (1998) observed the similarity between the messages contained in kanga inscriptions and the sentiments expressed by the taarab singers, both providing vehicles which allow Swahili women to voice opinions which cannot be overtly stated and to become involved in everyday personal or local disputes and rivalry. So successful were both kanga and taarab in this role that legislation had to be brought in to regulate the vehemence with which they were being used.

So kangas give women a chance to speak of things they can’t normally?

As Parkin (1998) observes in discussing Swahili proverbs: “..their often elliptical character is also said to be typical of a society whose stress on concealment (setiri) and secrecy (siri) is paradoxically part of proper manners (adabu) as well as the cause of tension (fitina)”. The unspoken language of the kanga provides a way of suggesting thoughts and feelings which cannot be said out loud, and of relieving suspicions and anxieties which inevitably arise. HAMWISHI KUNIZULIA HICHO NI CHENU KILEMA – “Your problem is that you can’t stop backbiting” says the inscription on a kanga with the traditional kisutu design in black, red and white; an alternative meaning suggested to me by Hassan Arero adds a characteristically Swahili nuance to the inscription: “Your main shortcoming is to obstruct me and hinder my progress”.

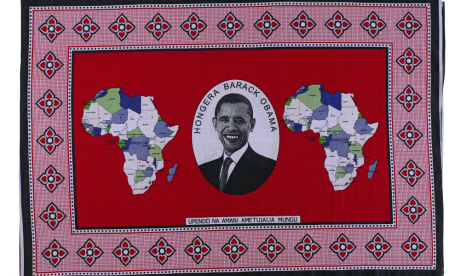

Tell us about the political messages in kangas.

Kangas may carry political or educational messages, though today the HIV epidemic seems to have driven away these didactic messages from the kanga, replacing them with exhortations to put trust in God and not set too much store by worldly goods: KILA LENYE MWANZO LINA MWISHO – “Whatever begins must come to an end” declares a kanga with a design of tamarind seed pods from which a bitter-sweet drink is traditionally produced.

There is often a subtle link of this type between the pattern and motifs employed on the kanga and its inscription. For example, a kanga with the following inscription has a design of zingifuri fruit running around its border: USIONE NI KIMYA NINA MENGI MOYONI – “I may be quiet but there’s a lot in my heart”. The zingifuri fruit has a prickly exterior, but its flesh is used for a variety of social and cultural activities including the colouring of food, dyeing of grasses used in matting, colouring the hair and even for the Hindu caste mark.

The British Museum's exhibition, Social fabric: African textiles today, features fabrics from southern and eastern Africa. The exhibition will run until 21 April 2013 and entrance is free. The book that accompanies the exhibition, African Textiles Today, can be purchased online from the British Museum website.

The British Museum's exhibition, Social fabric: African textiles today, features fabrics from southern and eastern Africa. The exhibition will run until 21 April 2013 and entrance is free. The book that accompanies the exhibition, African Textiles Today, can be purchased online from the British Museum website.