Elspeth Callender heads to Mauritius on a mission to trace her roots.

In 1880 a sailing ship entered Sydney Harbour in heavy seas. Two girls - Wilhelmina and Bella - were allowed to remain on deck for their first glimpse of Sydney provided they were securely fastened with lifelines. Their mother, whose husband had recently died back in Mauritius, stayed below decks with her son.

Wilhelmina was my great-great grandmother.

Mauritius has always been as mysterious to me as Australia probably was to those windblown immigrants.

A tropical island off the east coast of Africa where the dodo once dawdled and locals chat in French creole. A place I've felt increasingly compelled to visit.

Among my reasons for travel, this instinctive return to the old country in search of ghosts is a first. Though, as a place to chase ancestral roots or just explore for fun, Mauritius is manageable. It's less than half the size of South Australia's Kangaroo Island with only one city, four towns and lots of small villages.

Flying in, the island looks as green and coral reef-ringed as I expected but, on the ground, there's a surprise. Although Mauritius was a British colony until its independence in 1968 and, before that, a slavery-practising French colony, the most predominant influence is Indian.

From the ridge-top citadel overlooking the pastel-coloured capital of Port Louis - a small city positioned between peaky green mountains and the Indian Ocean - my guide for the week enlightens me. Clifford explains that when slavery was abolished in 1835 it heavily affected local industries, such as sugarcane, and indentured labour from India was the colonial "solution".

Aapravasi Ghat, the historic dockside immigration depot, pays tribute to those hundreds of thousands of arrivals. Mahatma Gandhi Institute is dedicated to tracing their personal histories.

Clifford's mother is Indo-Mauritian and his father Madagascan. His hometown of Vacoas (pronounced var-kwa) is predominantly Hindu yet accommodates mosques, churches and Buddhist temples.

He identifies as Christian but has twice joined the annual Hindu pilgrimage of Maha Shivaratri, mainly for weight-loss purposes, while his Hindu wife has never partaken. None of this is atypical for Mauritius. "The great advantage to being a multi-cultural country," Clifford tells me, "is that there are 18 public holidays."

It's Sunday, so trawling national archives and civil status offices is on hold. I'm happy just to hang around for the day where my ancestors lived, died and waved goodbye.

Strolling the shady grounds of St James Cathedral, I imagine the service inside is the 1876 funeral that catalysed my ancestors' dispersal. On the street where their townhouse no longer stands, Chinese locals tell us it's been a Chinese street for more than 50 years.

Port Louis has obviously changed a lot since Wilhelmina departed. Colonial remnants can be found around the city: derelict wooden houses supported between new concrete structures and preserved stone buildings - made with volcanic rock originally cut by slaves - on surviving cobbled streets. Newer buildings on the port have been designed to look historic while one of the oldest is currently a carpark.

A few kilometres from the city's moderately frantic congestion, at Eureka, I get a better sense of what Mauritius might have been like during Wilhelmina's time.

Over a freshly prepared creole meal on the verandah of this 200-year-old sugar plantation homestead, I also get why Europeans cut motherland ties in exchange for life in Mauritius.

The 109-door house is decorated to loosely represent the colonial era apart from two rooms painted, slapdash, in red and green. A Bollywood film was recently set there, I'm told, so the gaudiness is temporary.

During a cooking demonstration on the lawn, I decide to flash some ancestral photos to the locals I'm standing with.

The first woman immediately points at Wilhelmina's portrait: "But she's an Indian, no?"

"Yes, she looks very Indian," agrees the next.

"She looks like me," says the woman cooking. Then they all do this slow nod to each other with raised eyebrows.

"We say in Mauritius," Clifford explains, "that people slept with the windows open back then."

I look at Wilhelmina's face with fresh eyes in the bright Mauritian sun and realise that, no, she is not an obvious combination of her parents - one of Scottish descent and the other French.

Over the next few days, Clifford and I take breaks from trying to locate Wilhelmina's birth certificate to wander the lusciously overgrown Western Cemetery in search of family graves.

One day we take the afternoon off to hike the country's third highest peak, Le Pouce ("the thumb"), and feast on Chinese guavas that grow along the trail. At the summit we meet three chaperoned Bangladeshi women in matching bright yellow saris and bare feet, taking a break from work in the Mauritian textile industry.

That evening we dine in the far north on a coastline now packed with beachside resorts. Possibly the last of its kind in Grand Baie, Nizman Snack is a family home with a single restaurant table set up in the living room. We gorge on seafood salad, boiled noodles and deep-fried prawns until we're bursting. Then crab curry and roti appear. To buy some digestion time, I whip out Wilhelmina's photo. The family gather round.

"But she's an Indian, yes?"

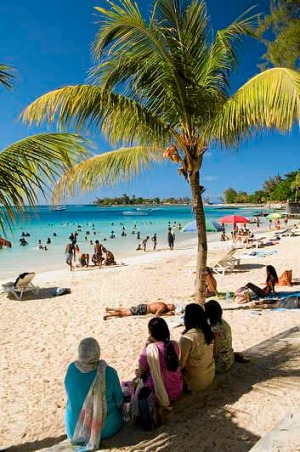

Eventually I leave the paperwork behind to explore the island's cooler, wetter south. It's where Clifford feels "in his element" because of the climate, crater lakes, national park, massive banyan trees that hang over the roads like unruly fringes. There's also tea degustation at Bois Cheri, rum tasting at St Aubin and weekend beaches full of locals.

On the way to the airport for my departure, Clifford stops in the town of Plaine Magnien. We eat mutton dhal in a hole-in-the-wall restaurant then trawl the lit-up snack shops along the main street for Indian sweets. It may have been family that drew me to Mauritius in the first place, but it will be so many other things will bring me back.

The writer was a guest of Mauritian Tourism Promotion Authority.

FIVE WAYS TO RECONNECT WITH YOUR PAST OVERSEAS

BE PREPARED

Leave home with a good understanding of your family tree and with all your information organised in a way that's easy to access while travelling.

CARRY PHOTOGRAPHS

Take copies of relevant family images with you. This gives people something tangible to see and helps get them interested.

HAVE A GUIDE

Even in an English-speaking country the assistance of a knowledgeable local will fast-track your research.

BE PRODUCTIVE

Do as much work as you can when you're there, because the chance of things progressing greatly diminishes as soon as you leave.

TAKE IT EASY

You're delving into another country's bureaucracy, so keep your agenda flexible or you'll end up getting hot and bothered or cold and grumpy.

GETTING THERE

Air Mauritius has a fare from Sydney and Melbourne (via Perth) to Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam International Airport for about $1605, including tax, low-season return. Perth to Mauritius is about eight-and-a-half hours; see airmauritius.com; phone 1800 247 628.

STAYING THERE

Merville Beach Hotel is a relaxed northern beachfront resort in Grand Baie; see mervillebeach.com. Double standard rooms for two people (buffet breakfast and dinner included) from MUR6600 ($230) during low season.

Outrigger is a secluded beachfront luxury resort and spa in the south at Bel Ombre; see outriggermauritius.com. Rooms from MUR7100, breakfast included, during low season.

SEE + DO

Emotions Destinations Management offers guides, such as Clifford, for full-day customised excursions for around MUR4650. See aboveandbeyondholidays.com.au.

Eureka is open every day from 9am and offers guided tours, tea on the lawn, cooking demonstrations, lunch and even accommodation. See maisoneureka.com.

TRIP NOTES

MORE INFORMATION

tourism-mauritius.mu.